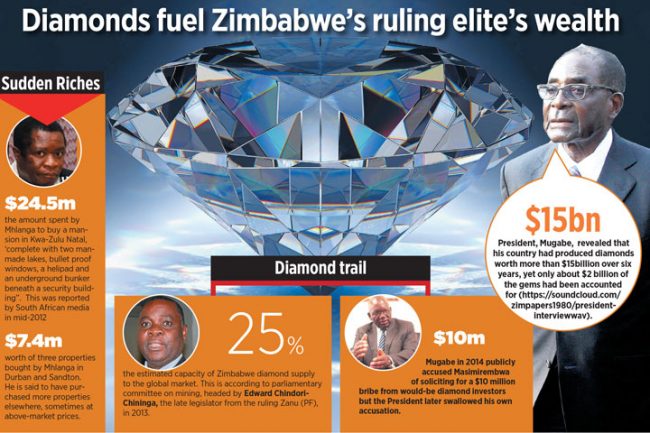

president, Robert Mugabe, got the world jawing angrily in early March this year. He used his traditional birthday interview with State television to reveal that his country had produced diamonds worth more than $15billion over six years, yet only about $2 billion of the gems had been accounted for (https://soundcloud.com/zimpapers1980/president-interviewwav).

He dumped the stinking carcass at the doorstep of the eight mining companies that had been operating in the sprawling diamond fields of rural Marange in eastern Zimbabwe and claimed he had no clue how the leakages happened. That way, the 92-year old statesman who has been in power for 36 years skirted, quite conveniently, the role played by the ruling elite in the leakages.

The common tale is that diamonds were discovered in Marange in 2006. Thousands of poor illegal miners swamped the area and fed local and international underground syndicates with the gems until 2008 when the governments sent in soldiers to violently flush out the hungry alluvial gem miners. This paved the way for commercial production that commenced on a low note in 2009. By 2015, a total of eight companies were extracting the diamonds, with most of them in joint ventures with the government.

Diamond trail

The discovery of diamonds in the area dates far earlier than the gem rush in 2006, though. De Beers, the world’s largest diamond company, held an Exclusive Prospecting Order (EPO) over Marange from the early 1980s via a subsidiary, Kimberly Searches Ltd. This order expired in 2006 and the British-registered African Consolidated Resources (ACR) took over the exploration rights. ACR challenged government’s subsequent takeover of the mining rights and initially won through a High Court order but the same court reversed its decision in September 2010.

A parliamentary committee on mining, headed by Edward Chindori-Chininga, the late legislator from the ruling Zanu (PF), estimated in a June 2013 report that Zimbabwe had the capacity to supply 25 percent of the global market from Marange and a couple of mines elsewhere. However, there were repeated concerns from civil society, opposition politicians, international watchdogs and some government officials that not much was coming out of the gem fields amidst widespread reports that the diamonds were being systematically carted out of the country to various destinations.

By 2014, alluvial diamond deposits were running ultra-thin, meaning that extraction had to go deeper in search of conglomerates, but the mining companies were ill-prepared for the tech-intensive development. Late last year, government expressed dismay at the “mysterious” losses of diamonds. It announced that it would be stopping the mining companies so as to form a consolidated outfit that it is now spearheading.

Sudden Riches

Zimbabwe has nothing to show for six years of the multi-billion commercial diamond mining that attracted mostly negative international attention for human rights abuses at the gem fields and a looting frenzy by Mafia-type syndicates. The signature of the ruling elite looms large in the leakages. Senior government officials and their allies closely linked to diamond extraction, tellingly, amassed overnight riches whose sources have remained a mystery.

Obert Mpofu was the Mines and Mining Development minister between 2009, when commercial mining commenced, and late 2013 when President Mugabe shifted him to the transport portfolio in a cabinet reshuffle. He had been in business for a long time, but his profile was modest until he landed the mines ministry. His high value investments subsequently straddled transport, banking, tourism, properties, mining, ranching and the media. At one time, he was rumoured to own half of the world-famous resort town of Victoria Falls.

Mpofu’s empire started crumbling when he was moved from the mines ministry. The Zimbabwe Mail newspaper he jointly owned with Robert Mhlanga, a former senior Airforce of Zimbabwe officer who chaired the board of Mbada Diamonds, one of the leading mining companies, collapsed when Mpofu left the mines ministry. So did Allied Bank which he had bought during his tenure at the ministry. The minister insists his hands are clean and claims he built his wealth from a golden handshake he got when he left a Zanu (PF)-owned company, Treggers, in the late 1980s.

His tale has not convinced many. Sceptics include former Finance minister under the 2009-2013 Government of National Unity (GNU), Tendai Biti, who now leads the People’s Democratic Party (PDP). “Obert Mpofu has a lot to explain to Zimbabwe and the world over how he handled our diamonds. He must be brought before an independent commission of inquiry,” Biti told Africa Review. He is bitter that President Mugabe protected Mpofu from cabinet scrutiny during his tenure at the mines ministry. Biti accused Mpofu of barring him from directly engaging with the mines following poor receipts into Treasury, repeatedly forcing him to revise national budgets downward.

Mpofu, 66, illegally appointed or influenced the appointment of most of the people to represent government stakes in various companies involved in Marange diamond production and marketing, according to a parliamentary study that was headed by Chindori-Chininga. The legislator, a former Mines minister, came from the ruling Zanu (PF) and died in a mysterious car crash months after the release of the dThe report is brazen in its condemnation of Mpofu who signed himself off as Mugabe’s “Ever Obedient Son”. “Board appointments… were being done by the Minister of Mines in clear violation of Section 5(2) of the ZMDC Act… Due to the unilateral appointments by the Minister, certain individuals with a conflict of interest were appointed.” Four key individuals with Zanu (PF) links are named. They must have been disqualified from sitting on boards of the companies because they held shares in some of the diamond firms.

Robert Mhlanga is a name that sticks out prominently. Mhlanga, who was the chairperson of Mbada Diamonds, was a shareholder in Liparm, a subsidiary of the giant mining company that the Chindori-Chininga report said was arrogant and untouchable. Besides jointly owning the Zimbabwe Mail with Mpofu, he shared more than his first name with the Zimbabwean president. He is a former Air Vice-Marshal in the Airforce of Zimbabwe (AFZ) and was Mugabe’s helicopter pilot for a long time. Uncorroborated reports claimed he represented Mugabe’s business interests and the president was the one who directly ordered his appointment as Mbada chair. He was also implicated in a 2002 sting operation against Morgan Tsvangirai, the MDC president, who was then accused of treason for allegedly plotting to “exterminate Mugabe” but the opposition leader was subsequently acquitted.

Mhlanga made big news when he acquired prime real estate on the Durban north coast and Sandton in Johannesburg, South Africa. South African media reported in mid-2012 that Mhlanga had bought a US$24.5 million mansion in Kwa-Zulu Natal, ‘complete with two man-made lakes, bullet proof windows, a helipad and an underground bunker beneath a security building”. Some said the mansion would be Mugabe’s get-away or retirement home but no proof has been provided yet. Deeds records in South Africa show that, in one day in January 2011, Mhlanga bought three properties worth US$7.4 in Durban and Sandton and purchased more properties elsewhere, sometimes at above-market prices.

Other officials associated with Mpofu played key roles in the diamond industry. Goodwills Masimirembwa was the chairperson of ZMDC, the government arm tasked with overall diamond production as well as the establishment of mergers, and which had 50 per cent ownership in most of the mining firms. Masimirembwa has been following Mpofu wherever he goes.

Prior to his ZMDC appointment, he was the chairperson of a pricing commission that fell under the ministry of Industry and Trade that Mpofu headed. When Mpofu was moved to the transport portfolio, Masimiremembwa resurfaced as the chair of CMED, a government parastatal under the ministry, but he was fired when his godfather was last year moved to Macro-Economic Planning and Investment. Mugabe in 2014 publicly accused Masimirembwa of soliciting for a US$10 million bribe from would-be diamond investors but the President later swallowed his own accusation.

Mr Mpofu declined to comment when contacted by Africa Review. “I am not commenting on this because I am no longer the minister of Mines,” he said. Mr Mhlanga and Mr Masimirembwa did not respond to several requests for comment.

Official confirmation

There is official confirmation of the role played by political bigwigs in protecting local and international illegal diamond dealers. The current Mines and Mining Development minister, Walter Chidhakwa, in March this year toured Manicaland province where Marange is located and had no kind words for the senior politicians. “We want to see the politicians who protected them (the syndicates) to loot this country,” said Chidhakwa.

There are also anecdotes that point an angry finger at army generals who could have taken advantage of murky shareholding at one of the big mining companies, Anjin Investments. ZMDC insists a Chinese company, Anhui, owned 50 per cent of Anjin while the corporation had 10 per cent and government 40 per cent.

It has never been explained which part of government owned the 40 per cent and why that was so, given the fact that ZMDC is a government unit, but observers say the share belonged to the security sector. Anhui is, in fact, thought to be a proxy of the Chinese military.

The secret ownership by the Zimbabwean security sector is believed to have given generals the chance to divert proceeds from Marange for personal gain and funding of covert military and intelligence operations. Indeed, several shadowy projects were set up in the run-up to the 2013 general elections and these were funded from diamond proceeds. A Zanu (PF) propaganda newspaper, The Patriot, for instance, bought numerous new vehicles during this period and paid its staff well despite having low circulation and failing to attract advertising.