It was 1972. Thousands of American troops were battling communist forces in Vietnam. Nixon had won re-election by a landslide, but Watergate would soon usher in his demise. Space travel and technology were advancing rapidly.

Change was brewing across America, but one place stood still, frozen in time: Louisiana State Penitentiary, commonly known as Angola. When Robert King arrived that year, he felt as though he’d stepped into the past.

Angola sits 50 miles northwest of Baton Rouge. It’s the largest maximum-security facility in the United States and one of the country’s most notorious prisons. In the book The Life and Legend of Leadbelly, the authors wrote, “Tough criminals allegedly broke down when they received a sentence to Angola. … None of them wanted to be sent to a prison where 1 of every 10 inmates annually received stab wounds and which routinely seethed with black-white confrontations.”

Angola’s expanse covers a vast 28 square miles — larger than the size of Manhattan. Tucked away in a bend of the Mississippi River, it’s surrounded by water and swamp on three sides. It’s an isolated penal village — the nearest town 30 miles away — and it’s the only penitentiary in the country where staff members live on site. Generation after generation grow up, live and die on Angola’s land.

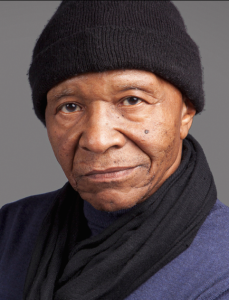

When King, now 71, arrived at Angola, his first impression of it was that it resembled a slave plantation, he said. And it used to be just that. Its name is derived from the home country of the slaves who used to work the land. Today, the comparison remains sadly accurate: Inmates are disproportionately black. They’re forced into hard labor and monitored closely by armed white staff on horseback. There is a sex slave trade behind the bars and many black inmates are deprived of basic constitutional rights.

King landed a tough lot in life: He was born black in Louisiana in 1942. In his 2008 book From the Bottom of the Heap, he wrote, “I was born in the U.S.A. Born black, born poor. Is it any wonder that I have spent most of my life in prison?”

He went to Angola when he was 18 for a murder he did not commit and remained there for 31 years, 29 of which he spent in solitary confinement, before he was finally freed in 2001.

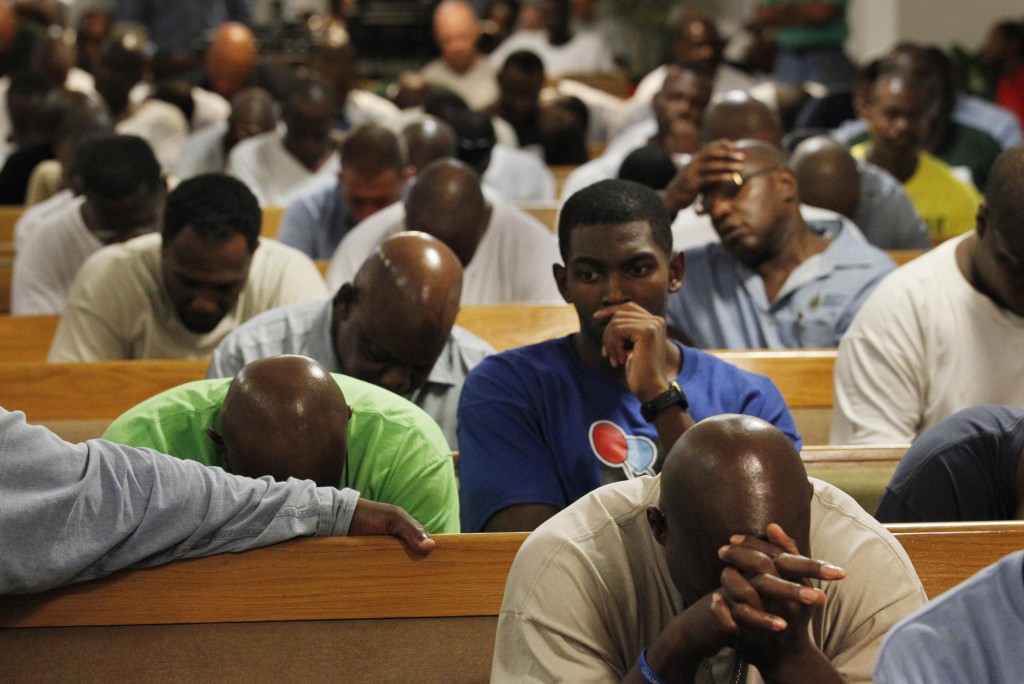

In 1972, the prisoners were virtually all black. Merciless guards — all white men, called “freemen” — worked the inmates like slaves. Sugar cane was the main crop, King said. In the documentary film In the Land of the Free, it’s stated that the inmates labored all day every day for a measly $.02 per hour. The abuse didn’t stop there. As NPR reported, “There was a prisoner slave trade and rampant rape; inmates slept with J.C. Penney catalogs tied to their waists for protection.”

King was one of three men who formed the famous Angola 3 group, leaders of the Black Panther Party’s Angola chapter. King said they were fighting for equality, but he later realized their efforts had been misaimed: “We were focused on civil rights, but we didn’t have human rights,” he said.

In our most recent conversation, I asked King, “How’s it going?” “It’s … ongoing,” he replied. It’s easy to see why: Little has changed at Angola. It remains a time warp, a living, breathing relic of a shameful past. Of about 6,000 inmates currently in custody, roughly 70% are black and 30% are white. In October 2008, NPR reported, “In the distance on this day, 100 black men toil, bent over in the field, while a single white officer on a horse sits above them, a shotgun in his lap.”

The context of this modern day slave plantation is unfortunately appropriate. Nola.com wrote that Louisiana is the world’s “prison capital,” with 1 in 86 residents serving time — nearly double the national average. The racial skew is extreme. One in 14 black men in New Orleans is behind bars; 1 in 7 is either in prison, on parole or on probation. Louisiana is “notorious for racial disparities in its justice systems,” Andrew Cohen wrote in the Atlantic.

One highly concerning aspect of Louisiana’s judicial scheme is that, unlike in 48 states, a unanimous jury decision is not required — only 10 jurors have to vote to convict someone, even for a life sentence. Oregon is the only other state with this system, but it doesn’t have the same tremendous racial component.

Cohen wrote, “Prosecutors can comply with their constitutional obligations to permit blacks and other minority citizens to serve as jurors but then effectively nullify the votes of those jurors should they vote to acquit.” It is one of “the most obvious and destructive flaws in Louisiana’s broken justice system,” he wrote, arguing, plain and simple: “Louisiana is terribly wrong to defend a law that was born of white supremacy.”

A Duke University study examined more than 700 non-capital felony criminal cases in Florida and found that, in cases with no blacks in the jury pool, blacks were convicted 81% of the time while whites were convicted 66% of the time. The researchers concluded that “the racial composition of the jury pool has a substantial impact on conviction rates” and that “the application of justice is highly uneven.”

For a black defendant, facing an all-white jury is not uncommon. In King’s trials, the juries were all white, with one black person. This past March, Glenn Ford, 64, walked out of Angola a free man after 30 years on death row. He was Louisiana’s longest-serving death row prisoner, yet he’s just another black man who was convicted and sentenced by an all-white jury.

King said Angola today still reminds him of a slave plantation, but not as much as it reminds him of a graveyard. “There seems to be an artificial sanitation that is disturbing to me,” he said. The land is “beautiful, whitewashed, looks like a college campus.” But underneath, “The bones are rottin’.”

Angola exists in the shadow of slavery, a time when black men did not have rights. In a state with the motto “Union, justice and confidence,” there is certainly a lingering stink of a bygone, ugly era for which “union and justice” is simply not a fitting description.

The other two members of the Angola 3 are Albert Woodfox and Herman Wallace. There is overwhelming evidence of their innocence and accordingly, state and federal judges have overturned Woodfox’s conviction three times, citing racial discrimination, misconduct by the prosecution and inadequate defense. But Louisiana’s Attorney General James “Buddy” Caldwell holds the ultimate power, and has contested the rulings, claiming they were based on technicalities.

To this day, after 42 years, Woodfox remains in solitary confinement in Angola. He’s thought to be the longest-serving inmate in solitary. In the documentary film, he says, “If a cause is noble enough, you can carry the weight of the world on your shoulders. And I thought my cause, then and now, was noble. So therefore, they would never break me.”

“They might bend me a little bit. They might cause me a lot of pain. They may even take my life. But they will never be able to break me.”

Wallace was released in October 2013 with advanced liver cancer. King went with Woodfox, who was permitted to leave briefly, to visit their friend and tell him he was out of Angola for good. “We told him,” King said. Wallace couldn’t move or respond. “[But] we saw it in his eyes. … He knew he was getting out.” Wallace took his last breaths a free man, after over 40 years. He died three days later.

King continues the fight for Woodfox. So when he is asked about his own release, he responds with this apt adage: “I was free of Angola, but Angola would not be free of me.”

Image Credits: AP, Peter Puna, Robert King