Amaal Said is a Danish-born Somali poet and photographer, living just outside London. She is 20 and a politics student at SOAS, University of London. Like many people her age, she spends a lot of time in her bedroom, listening to pop music and browsing YouTube. While she does all that, though, she is quietly revolutionising the way Muslim women and women of colour are portrayed in our culture. Her photography, and the Instagram account where she features it, has started garnering her international attention. Her poetry is also getting her places – she has been a Barbican Young Poet, in 2015 won the Wasafiri New Writing Prize for poetry, and is an active presence in the London spoken word scene.

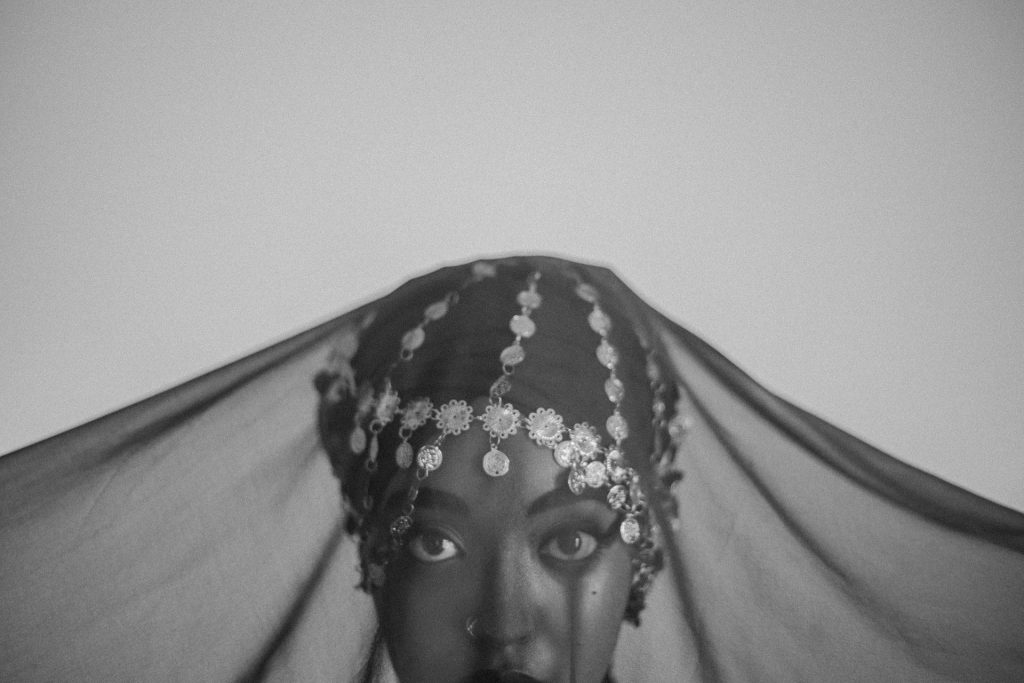

Said’s photographs are sensual, sensitive, almost mystical. They are tranquil and vibrant at once, playing with clothes, nature and cityscapes. But their power goes well beyond the aesthetics – Said uses her images to carve a space in culture for the community of artists, poets and creative women she portrays.

We sat down with Said and three of the women she has photographed: Rachel Long, a poet, facilitator and founder of the Octavia Poetry collective; Rena Minegishi, a poet and student of a master’s degree in electronic music; and Sunayana Bhargava, a poet and astrophysics student. Here is their edited conversation about tokenism, being sexualised, the male and white gazes, how the internet has given them a community and self-image.

Photograph: Amaal Said

Carving a space for their voices

Rachel Long

I set up Octavia because, whenever we met at other poetry events, the conversations that we had didn’t really give us that space to talk, and we just had so much to say. And also we needed a space that was just for us, so it was outside of academic institutions, which were very white, very middle class, very male. It’s really important to know that just because you’re making spaces, it doesn’t mean you want segregation. Essentially, you’re making spaces so that you don’t need those spaces any more.

Amaal Said

I was writing about difficult things that I’d been told to keep hidden because the women in my family weren’t proud of it or they expected people to not understand. But I felt like I didn’t have a choice, because staying silent would mean internalising a lot of shame about my own body. I didn’t think it was fair to keep it all in, and so writing was an act to sort through and share those really heavy feelings. The incredible thing was being heard and being told that I wasn’t alone.

Rena Minegishi

I used to write about really big, abstract things, probably because I was born in Tokyo and grew up in Beijing, and I always felt like that was my biographical tagline. I think finding communities of like-minded writers and women let me shed those preconceived notions about how my poetry should be. Now I’m a lot more focused on documenting the intimate relationships in my life, like writing love poems, because I don’t have to feel cliched if I’m just going to read them in a room full of women. I’m not as tokenised in a room full of women.

Being typecast as ‘the woman of colour’

Amaal Said

Being very visible in terms of being Muslim, wearing a hijab and getting on a stage, and then being expected to say a sort of thing or have a sort of voice and to write the poem about the news, right? To write the poem about war … That’s not very fair on me, because I’m just a girl and I’m just going through my own stuff.

Especially being introduced: oh, look, we have Amaal Said, her work is very tragic or her work is very devastating, and I’m like: devastating for who? Because, for me, it’s just something else that I’m working through, it’s not something that cripples me.

Rachel Long

[There is] this expectation that […] you […] should write this kind of one-voice-for-all-black-voices and it should be female. You should be talking about your rough upbringing, your working-class background, stuff like that, which I didn’t necessarily want to do.

Sunayana Bhargava

I’m so much more than just an Indian woman. I’m [a woman] from a fairly difficult upbringing who also happens to do other kinds of things. I’m really interested in surrealism, for example. I’m really interested in piecing together surreal aspects of life. That’s come through in my poetry now, where I can write about far more difficult, hard-hitting things and not feel guilty for eviscerating myself on paper and writing all of these horrible things that people are like, “wow, how unfeminine, how unwomanly”. Because I choose the metric of womanhood for myself and nobody else can tell me what is or isn’t supposed to be feminine.

A lot of men are poets before they even walk into the room, and they never feel like they’re going to be typecast in any way, shape or form. The sad thing is the way that people have tokenised people of colour or women; they’ve expected them to bring certain narratives and systematically only included them if they’re going to bring those narratives to the table. So you end up in a double bind here because you’re like: well, I’m equally as human as my male counterpart, but I’m only allowed airtime if I’m speaking about the ways that I’m not like them, and the ways that I “earn” my grief and my pain.

Photograph: Amaal Said

Rejecting the male gaze

Sunayana Bhargava

I find that, a lot of the time, if a man were to come up to me and say something about how I lived through a domestic abuse situation or how I managed to grow up in a violent household, they would always commend me on managing to retain some level of femininity, some level of vulnerability and softness, as if I’m still palatable because I can still manage to present myself in a really feminine way. Whereas women are better at being critical and putting you on the path to what your authentic voice is.

Rena Minegishi

A male artist can approach you under the guise of “hey, we’re both creatives, it’s an artistic collaboration” – but it’s not! They just want to photograph you in a way they feel is attractive. Just thinking about the ego that comes with being a male photographer … It’s them thinking: “Rena’s not a person, she’s a muse. Rena’s not a partner, she’s just a beautiful girl in my room, she’s just a subject on the other side of the lens.” Why are we not seeing close-up penis shots more often? Not that I want to [laughs]. Why are we so commodified? If you have to use a conventionally attractive naked woman to make your photo worthwhile, maybe you’re just not a great photographer. If you can’t make an exciting photo without sexualising a woman, maybe you need to practise.

Photograph: Amaal Said

Advice for female artists

Rachel Long

Your voice is valid and necessary – that’s a mantra you have to keep repeating. Because that belief gets chipped away. Read, read, read so much. Because you’ll never be good if you don’t read, you’ll never be able to write well. Also, if you are the weirdo kid and you are on your own, you’re isolated, that’s really hard – but make a community any way you can, even if it’s a community of two. Use the internet, just so you’ve got someone to bounce ideas off when you need it. That can add a lot to your confidence – somebody who likes your work, but whom you love and trust enough that they can critique your work as well. Because you’re not going to get any better without realising that you do need critique.

Sunayana Bhargava

No matter what you’re saying, people are going to tell you that there’s no need for you to say it. There’s no need for you to paint; there’s no need for you to photograph; there’s no need for you to write music, because in some way, shape or form, you’re not going to be changing anything. That’s all a big bargain game to make sure you never overstep your mark, never go out of yourself, never breach your remit as a woman working as a creative. So persevere to make sure you never let anybody tell you that you don’t have a place in art.

Rena Minegishi

Read more women. You will find a resonance so deep and so real once you read women poets, because they know exactly what you’ve been through, they’ve been talked down by male poets, they’ve been erased from textbooks.

Photograph: Amaal Said for the Guardian

Owning the title ‘artist’

Amaal Said

I feel like I’ve been fighting for the term “artist” for a very long time. People I’ve grown up around have always tried to take away the artist label from me: you’re just a daughter, you’re a politics student, etc. You can’t be more than one thing, but men can. For me, it literally took the publishing of the first book Warsan Shire released, Teaching My Mother How To Give Birth, to be able to break down to my mother that this is what I wanted to do. I remember getting it and waving it in her face, like, “Look! She’s actually Somali and she’s doing this! And I’m not doing some kind of made-up thing!” Representation matters so much.

Rena Minegishi

I don’t for a second delude myself into thinking that I’m single-handedly responsible for a huge change in the creative world. But if I can begin to move an individual, if me doing that in public inspires a fellow creative who might feel discouraged, that’s what’s important to me.

Photograph: Amaal Said

The power of online communities

Amaal Said

I live such a solitary life. Knowing that what I’ve said and what I’ve experienced from my little part of the world can touch you from across the sea is why the internet and YouTube are so incredibly important. As a young Somali girl, and as a young black girl growing up in a place where there were no community services or youth groups and the nearest cinema was 30 minutes on a bus, having a space on the internet – opening yourself up to a community, sharing your work with maybe a couple of people at first, and just growing the confidence – is what it took for me to be able to say: I can do this and I’m not a fraud.

Sunayana Bhargava

I think the whole metric of how we measure change is very masculine. It’s done in a very aggressive, often violent way, that you need to break borders, upheave a whole structure in order to make a difference. But that’s not true at all – a lot of people unionise through the smallest things that operate over the largest distances. So, for a lot of us starting out in poetry, it was really validating to start in a digital sphere, before upgrading to what were more personal, intimate venues where you’d actually perform your work. I was reading about Beyoncé discovering Warsan Shire through YouTube, through exactly the same medium any other woman of colour would be able to access another woman of colour who’s reading poetry.

Representations and self-image

Rachel Long

Amaal’s not only doing something with women of colour in photographs – saying “I am here, we exist” – but also, crucially, her pictures are soft. They’re super feminine. Often times, black women are portrayed like the mummy figure: big and huge; it’s never soft. The black woman on TV is loud and brashy, she wears earrings and red hair and is really in your face. And so, through flowers and her photography, Amaal does the opposite. Even though you know that’s not the way every black woman is, to see that [softness] in a photograph is stunning.

Sunayana Bhargava

I had never felt comfortable in front of a camera, because I thought it was only going to magnify my flaws rather than finding something that I could like, but something about being in the hands of a woman that you really love and respect changed it from what would be such an interrogative experience. The idea that you could be with a woman and she could see beauty in you is an intensely vulnerable thing and something that requires a lot of trust. To be able to let Amaal take a photo of me and know that I’m going to see it and I’m actually going feel beautiful, is something that I think lots of women would feel is a massive thing, because they’re constantly looking at distorted representations of themselves. To see a picture of yourself and be like “hey, this is me, I just am”, I think that is beautiful.