When the United States bombed the Syrian town of Kobani in 2014 to stop it falling to Islamic State, the retired American general charged with building the military coalition against the jihadists, General John R Allen, said he would not use terms like “strategic target” or “strategic outcome” to describe the action, then added, “We are striking the targets around Kobani for humanitarian purposes.”

When President Vladimir Putin held a press conference in March 2014 and fielded questions about Russia’s involvement in Ukraine and the Crimea, he told journalists that any military action he took would be aimed at protecting people with whom Russia had close historical, cultural and economic ties. “This is a humanitarian mission,” he said. Everyone is a humanitarian now. A word once used to describe principled civilian assistance to people suffering in natural or manmade disasters now provides a reassuring gloss for the actions of politicians and the military. This has both compromised and endangered the work of aid workers who had believed that their independence and impartiality would be enough to protect them.

…

The starting point for this book was the big charitable aid agencies, the good guys of a $25bn aid business, and how they handle the pressures and dilemmas of the war on terror. At home they rely on public reputation and private donations to sustain their humanitarian endeavours, but in the field many deliver aid on behalf of western governments whose interest lies in countering terror.

Over the course of six months in 2013 and 2014, I travelled from Afghanistan, where the principal aid-funders have had boots on the ground for most of this century, to the Turkish border with Syria, where the west struggles to contain a jihadist threat far closer to home. In all four of the countries I focus on – Afghanistan, Pakistan, Somalia and Syria – the United States is conducting a bombing offensive, using either conventional warplanes or unmanned drones.

It is the war in Afghanistan that has defined the era for the non-governmental aid organisations, the NGOs. After 9/11 and the overthrow of the Taliban, most of them pitched in with enthusiasm to the huge and well-financed task of reconstruction. Afghanistan would be built anew, a beacon for what the west could do. But the old ways persisted, the war restarted, and the aid-givers lost their way. They were warned, as we shall see, that the drive for bigger budgets might be achieved only at the cost of their principles.

Afghanistan has widened a split in the humanitarian world. On one side are the big American and British agencies. Ever since the days of the cold war, US non-profits have relied on government funding. More recently British charities have established a similar relationship. Oxfam now derives nearly half its income from governments and other institutional sources. For Save the Children, the proportion is closer to two-thirds.

On the other side of the divide are the direct descendants of Europe’s greatest humanitarian institution. The International Committee of the Red Cross (ICRC) combines Swiss discretion with a solemn regard for the humanitarian principles it has formulated of independence, impartiality and neutrality. Governments may fund it, but the uniqueness of its status is secured by its guardianship of the Geneva conventions. With French flair, Médecins Sans Frontières (MSF) began life as a rebellious breakaway from the ICRC. It is now the most widely admired aid agency in the world. MSF has a mighty annual income of $1.1bn, or £750m, but gets less than a tenth of it from governments and takes none at all from belligerents in war zones. It does not even call itself an NGO, and once, in Pakistan, it went so far as to drop the tainted term “humanitarian”.

As traditional NGOs try to balance their own priorities with those of their backers, they have been joined on the frontline by a new breed of non-profit aid agencies for whom government contracts come first. In Washington they are the “Beltway bandits” in search of a share of the official US aid funds that have gushed from the ground since 9/11.

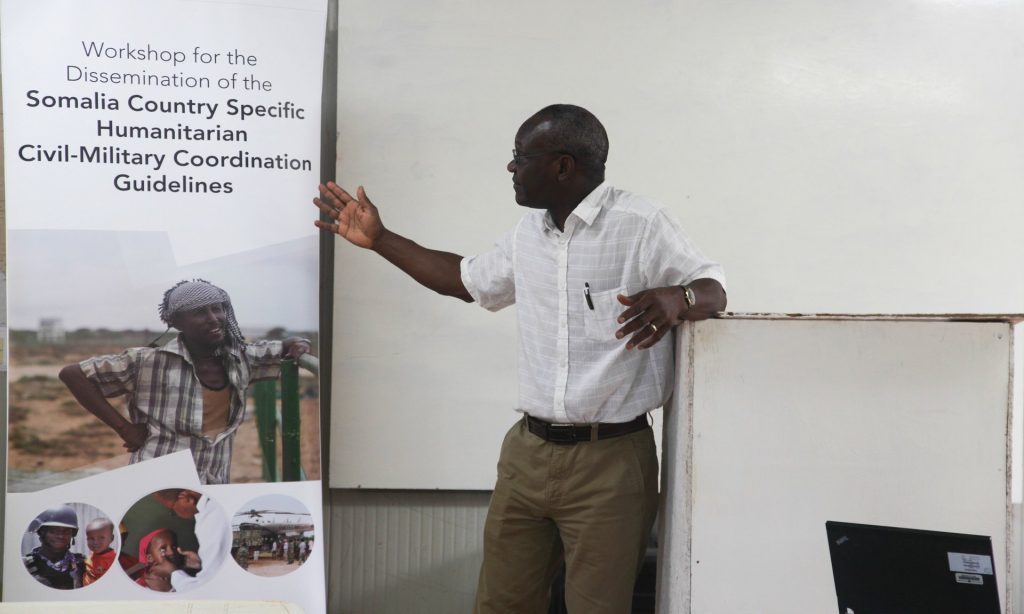

In Somalia, I stayed at a camp owned and operated by a US firm that cleverly combines profit-making in a war zone with NGO work that tackles Somali insecurity head-on. It hires ex-soldiers from around the world to “mentor” the African Union troops deployed in the country to counter Somali jihadists. That qualifies as charitable education work. The expectation is that greater security will one day make the country safe again for business, which is the firm’s longer-term interest in the country.

African Union forces are in Somalia with the authorisation of the United Nations, and that has pushed the UN’s own aid workers on to the frontline in the war on terror. Its great humanitarian institutions – the children’s agency Unicef, the refugee agency UNHCR and the World Food Programme – once enjoyed a measure of real independence from the UN’s political institutions, but they are now formally “integrated” into missions whose overriding task is to win wars for the security council in New York.

Photograph: Barut Mohamed/Amisom

The UN has become a priority target for al-Shabaab jihadists in Somalia. In 2013 its Mogadishu headquarters was attacked and it was forced to retreat to the better-guarded airport. When four Unicef workers were killed by a roadside bomb in northern Somalia in April 2015, the UN’s head of humanitarian affairs, Valerie Amos, issued this bleak statement: “Respect for the United Nations flag and the Red Cross and Red Crescent flag is disappearing.”

After Afghanistan, which remains the most dangerous country of all for aid workers, Somalia records the greatest number of hostile incidents. Around the world, the figures peaked dramatically in 2013 at 155 aid workers killed, 178 wounded and 141 kidnapped. “If you ask me today what is the greatest challenge for humanitarianism,” said Manuel Bessler, head of humanitarian aid for the Swiss government, “this is my first one, the security of my people. Without security for humanitarian workers, there won’t be humanitarian aid.”

We were speaking in June 2014, a few days after a Swiss Red Cross delegate was shot dead in Libya. “He was shot not because he was in the wrong place at the wrong time, but because he was targeted,” Bessler said. “People wanted to kill him as a humanitarian.”

Bessler began his career with the International Committee of the Red Cross. He recalls asking his instructors on the introductory course, “But what is our protection?” They told him, “The cross. The cross is your protection because the emblem is protected.” “Well,” Bessler says, “today the Red Cross is more like the cross hairs.”

Aid worker casualties declined in 2014, but this was attributed more to their reduced presence on the front line than to any change of heart on the part of their enemies. MSF produced a report that year which was sharply critical of the aid agencies. “Risk aversion was pervasive within the NGO community,” it found, “not only in relation to security but also to programming, meaning that agencies were choosing to prioritise the easiest-to-reach over the most vulnerable.”

By withdrawing to a safer distance, the concern was that the risks involved in delivering aid were being “outsourced” from international staff to local NGO workers. That might in turn account for an under-reporting of incidents and casualties. It was a western manager with a leading Muslim charity who told me that it was “morally wrong for aid agencies to transfer all responsibility and risk to local staff ”.

Today We Drop Bombs, Tomorrow We Build Bridges: How Foreign Aid Became a Casualty of War by Peter Gill is published by Zed Books (£12.99)