In our series of letters from African journalists, Nigerian novelist and writer Adaobi Tricia Nwaubani recalls how she was banned from speaking her mother tongue.

My parents forbade my local language, Igbo, from being spoken in our home when I was a child.

Unlike the majority of their contemporaries in our hometown of Umuahia in south-east Nigeria, my parents chose to speak only English to their children.

They also conversed between themselves in English, even though they had each grown up speaking Igbo with their own parents and siblings.

On the rare occasion my father and mother spoke Igbo with each other, it was a clear sign that they were conducting a conversation in which the children were not expected to participate.

Guests in our home adjusted to the fact that we were an English-speaking household and conformed, with varying degrees of success.

Our live-in domestic staff were equally compelled to speak English.

Many arrived from their villages unable to utter a single word of the foreign tongue, but as the weeks rolled by, they began to string complete sentences together with less contortion of their faces.

Over the years, I endured people teasing my parents, usually behind their backs, for this decision. “They are trying to be like white people,” they said.

Similar accusations were levelled against Lee Kuan Yew, Singapore’s former prime minister, when he replaced Chinese with English as the official medium of instruction in schools.

But, as he explained in his autobiography, From Third World to First, “With English, no race would have an advantage…. English as our working language has… given us a competitive advantage because it is the international language of business and diplomacy, of science and technology.”

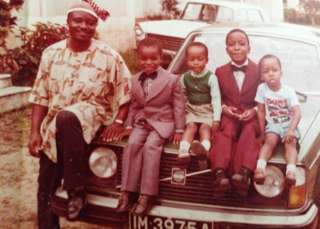

Adaobi Tricia Nwaubani:

“Local languages were part of the curriculum, but speaking them beyond the classroom was a punishable offence”

My parents seemed to share these convictions.

Each time it was my turn to stand and read to my primary school class from our recommended Igbo textbook, the pupils burst into a giggling session at my placement of the wrong tones on the wrong syllables.

Language tests

Again and again, the teacher made me repeat the words. Each time, the class’s laughter was louder. My off-key pronunciations tickled them no end.

But while the other pupils were busy giggling away, I went on to get the highest scores in Igbo tests. Always.

Because the tests were written – they did not require the ability to pronounce words accurately.

The rest of the class may have been relaxed in their knowledge of the language and so treated it casually, probably the same way a reckless Briton might treat his or her study of English.

I, on the other hand, considered Igbo foreign and so approached the subject studiously.

Igbo banned in school

I also read Igbo literature and watched Igbo programmes on TV. My favourite was a comedy titled Mmadu O Bu Ewu?, which featured a live goat dressed in human clothing.

Speaking Igbo was also banned in the boarding school I attended.

The Federal Government Girls’ College, Owerri, was one of the country’s “Unity Schools” founded after the Nigerian civil war to promote integration among ethnic groups and to discourage divisions and tribalism.

Local languages were part of the curriculum, but speaking them beyond the classroom was a punishable offence.

And so, under the tutelage of some of the country’s best teachers, I continued my ardent study of Igbo, despite not having the opportunity to practise how to speak.

By the conclusion of secondary school, I was confident enough in my knowledge of Igbo to register it as one of my subjects of choice for the university entrance exam.

Everyone thought I was insane. Taking a major local language exam as a prerequisite for university admission was not child’s play.

Results for language exam

I was treading where expert speakers themselves feared to tread. I still meet many Igbos who have been speaking the language all their lives, but are unable to read and write it fluently.

On the appointed day, presided over by supervisors in premises outside my school, less than six of us sat in the large hall, never mind that the exams were taking place in an Igbo town.

When the results were eventually released, my score turned out to be good enough, when combined with my scores in the two other subjects I chose, to land me a place to study psychology at Nigeria’s prestigious University of Ibadan.

In Ibadan, south-west Nigeria, home to the Yoruba ethnic group, I was free to speak Igbo at last.

Far away from home, from the giggling voices, and from those who did not allow me to speak Igbo, I was finally free to express the words that had been bottled up inside my head for so many years – the words I had heard people in the market speak, read in books and heard on TV.

Speaking Igbo in university was particularly essential if I was to socialise comfortably with the Igbo community there, as most of the “foreigners” in the Yoruba-dominated school considered it essential to be seen talking their language. “Suo n’asusu anyi! Speak in our language!” they often admonished when I launched a conversation with them in English.

“Don’t you hear the Yorubas speaking their own language?” Thus, in a strange land, I finally became fluent in a mother tongue that I had hardly uttered my entire life.

An English-Igbo man

Today, few people can tell from my pronunciations that I grew up not speaking Igbo.

“Your wit is even sharper in Igbo than in English,” my mother insists.

These days, she enjoys it when I gossip with her in Igbo, although I still can’t get myself to speak the local tongue with my father who, despite being a typical Igbo man in many ways and a titled chief, has never regretted choosing English over Igbo.

And, for some strange reason, my eloquence in Igbo often regresses whenever I am in the presence of anyone who was privy to my days as a non-speaker.

Maybe it is the memory of their mockery that ties up my tongue.

Eager to show off my hard-earned skill, whenever I come across publishers of African publications, especially those who make a big deal about propagating “African culture”, I ask if I can write something for them in Igbo. They always say no.

Despite all the “promoting our culture” fanfare, they understand that local language submissions could limit the reach of their publications.

Now comes the BBC with its announcement that it will broadcast in Igbo, as part of the World Service’s biggest expansion since the 1940s. At last, the next generation of Igbo experts have an international platform on which to display their skills.

This article was first published on BBC.com

2 Responses

Your parents didn’t try at all for not bringing you up in your local dialect but thank God, you made use of the opportunity when it came.

Its very funny when one is banned from speaking his dialect. But honestly speaking its not supposed to be Sao cuz its mother’s tongues first.