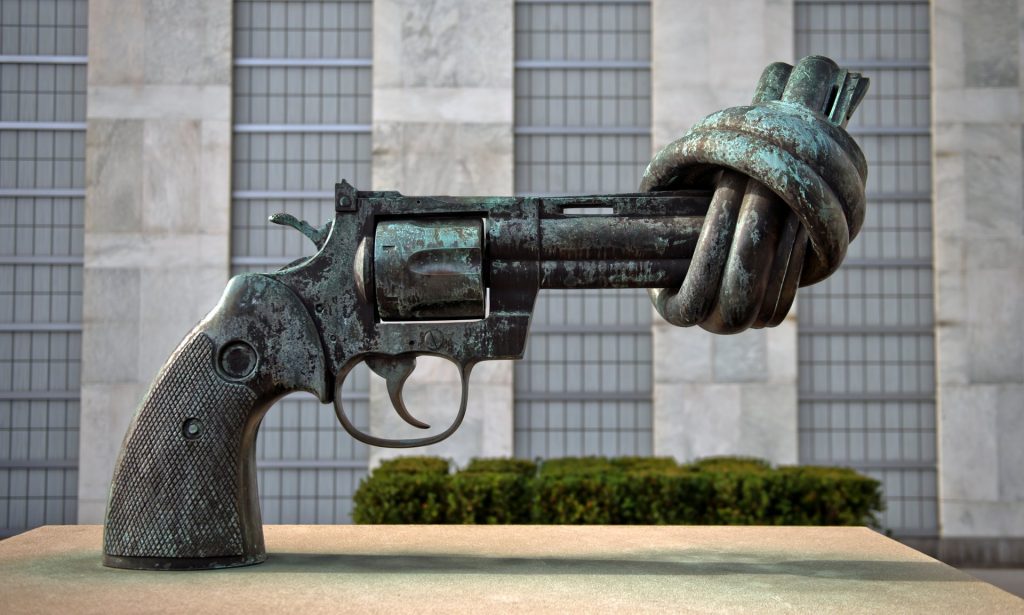

Photograph: Michael Gottschalk/Getty Images

War and violence cost the global economy $13.6tn (£10.2tn) in 2015, according to the annual global peace index. Terrorism is at a record high and the effects of conflicts in the Middle East and North Africa have been felt far beyond the region. Worldwide, a record 65 million people were forced to flee their homes last year, with one in every 113 men, women and children a refugee, internally displaced or seeking asylum. What are the implications of all this for development? Can the global goals be realised if countries are beset by conflict? Is progress impossible without greater emphasis on peace-building? We asked students to give us their views. Below is a selection of the best responses.

International collaboration on peace-building is paramount

In developing countries, peace and development often coincide.

[My country], Pakistan, was conceived out of a struggle for independence against the British followed by a bloody separation from India. At present, the country’s peace is severely compromised by Taliban attacks, sectarian violence and the international military operations of the US.

Pakistan developed a strong military and strove to become a nuclear power, often at the cost of social development. Like me, many would argue that conflict prevention, or preparation for war, has made the government take a narrow view of development and prevented it from realising its potential in terms of industrialisation and social development.

I believe engaging in the problem of chicken and egg, with respect to development and peace, is a digression. The need to collaborate on an international level to promote peace-building cannot be stressed enough, whether or not it is a condition of growth and development.

Zahra Khan, London School of Economics, UK

Development is on the back foot in Kashmir

As [the Indian economist and philosopher] Amartya Sen famously noted, “Freedoms are not only the primary ends of development, they are also among its principal means.” Development should be assessed by access to factors such as political and economic freedom, social opportunities, and protective security.

The [long-running conflict in] my homeland, India-administered Kashmir, has meant education, healthcare and environment haven’t been able to develop soundly. Unemployment is rampant; there is a lack of jobs for university graduates, and a lack of business investment.

Kashmir is under a curfew [imposed early in July] due to unrelenting unrest that has claimed more than 68 lives, with thousands wounded. Scores have received pellet injuries in one or both eyes, leading to loss of vision.

Development is on the back foot. Educational institutions have been closed, people can’t go to their jobs, the economy has plummeted and NGOs are being charged with sedition.

Unless there is some form of peace and stability, no human endeavour, however powerful and well-meaning, can lead to progress and development.

Madeeha Mukhtar, Government College for Women, Srinagar, Kashmir

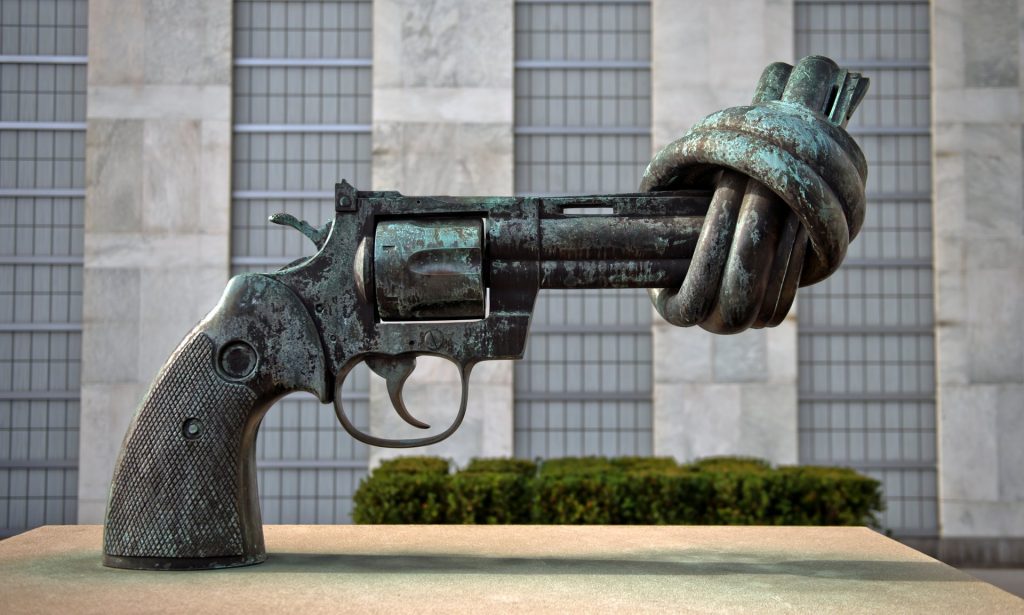

Photograph: Farooq Khan/EPA

Peace-building is less costly than relief efforts

Peace fosters conditions conducive to economic development. To promote an inclusive, sustainable and harmonious society, it is necessary to take peace-building measures. These measures should focus not on imposing solutions, but on the creation of economic, social spaces within which local people can identify, develop and employ the resources necessary to build a peaceful, prosperous and just society.

Peace-building programmes are less costly than relief programmes, and should be considered an investment for future development and a tool for steering the peace-building process.

Vaibhav Mishra, National University of Advance Legal Studies, Kochi, India

NGOs must tackle causes of conflict

Peace is a fickle and fleeting thing. Where I’m from – Belfast in Northern Ireland – peace is intrinsically linked to the cooperation of nationalists and unionists, Protestants and Catholics. It is tied to the idea of a peace process, whereby the Good Friday agreement, a treaty tied to the European convention on human rights, has defined how two opposite sects can live alongside each other in harmony.

But this peace is neither universal nor solid, as dissident groups and individuals seek to undermine it daily. Brexit has potentially catastrophic implications for the peace in Northern Ireland, first for the validity of the peace process itself, and second if there is further separation from the Republic by a physical border. As such, the region’s peace is at risk, as well as its development.

If sustainable development is to progress in poverty-stricken countries around the world, peacemaking must play its part. Money diverted to arms, and aid funding used to to repair the damage caused by conflict, takes away from investment in hospitals, schools and young people’s futures. However, it is the attitude that comes with war that is most significant, the placing of personal ambitions and strategies for power over the progression of the lives of your people. In Northern Ireland, rejecting this doctrine has so far enabled the fragile peace to endure.

Until this power-hungry perspective changes, NGOs must focus on how to control the cause of the conflict.

Lucy Keown, University of Glasgow, UK

Working collaboratively in conflict zones is vital

Development occurs in conflict. Local organisations can, in many instances, act more effectively than international organisations during conflict. Establishing trust and building relationships through transparent negotiations with other local groups allows workers certain access and protections that international organisations do not have. Relationships can be built with military forces, who are often less suspicious of local workers than international agencies.

In Syria, for example, locals have persuaded military powers to focus their attacks on legitimate military targets rather than civilians. They have also asked that schools take priority over hospitals – which will inevitably draw shelling – so that future fighters have at least some education.

If international organisations wish to contribute to development in areas of conflict, they need to focus their resources on supporting the needs and efforts of local people and workers, providing capability building, logistical aid and mental health support to those who experience death and destruction on a daily basis.

Alex Kirby-Reynolds, Goldsmiths, University of London, UK

Only peace can safeguard development

There is an indisputable connection between peace and sustainable development. History has shown that whenever a state’s peace has been threatened or suppressed, the recovery process has involved significant efforts to rebuild a stable society and repair interstate relations damaged by conflict. Peace can guarantee the human security of today, but also the sustainable development of tomorrow.

Andreea Botoş, Lucian Blaga University of Sibiu, Romania