We’re speeding down the road in a heavily armored convoy, heading towards the front lines of the battle against African Jihad. This is Boko Haram territory. Outside, the temperature can crack 110 degrees F.

We’re traveling inside a thick bubble of security protecting Samantha Power, U.S. Ambassador to the United Nations. She was there on a week-long diplomatic mission to Cameroon, Chad and Nigeria.

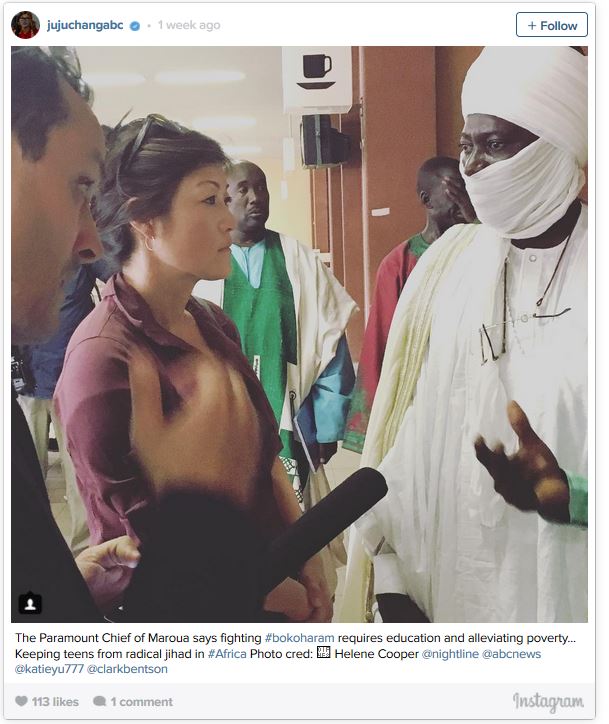

We’ve embedded with Power, known for having President Obama’s ear, as she meets heads of state, civic leaders and refugees. It seemed as though my producers, Katie Yu, carrying 30 pounds of camera equipment, and Clark Benton, I and want to get at two simple questions: What’s happened to the missing Chibok school girls? — It’s been two years since their brazen mass kidnapping trigged the global hashtag #BringBackOurGirls — And where are we in the battle against their kidnappers?

Last year, Boko Haram pledged allegiance to ISIS – renaming themselves Islamic State West Africa — stepping up slick propaganda and gruesome attacks.

In the years since First Lady Michelle Obama and countless celebrities and normal folk held up #BringBackOurGirls signs, the U.S. has deployed hundreds of special forces in advisory roles to the region. There’s also a surveillance drone base in Cameroon sharing intelligence with the African military units. But American soldiers aren’t the ones going into the Sambisa forest hunting down Boko Haram encampments. It’s the Nigerian military and a multi-national force winning a lot of territory against Boko Haram since they elected a new president last year.

But U.S. Brig General Donald Bolduc, the Deputy Director for Operations for United States Africa Command, says the Islamic insurgent group seems to be stepping up asymmetrical attacks, adopting some of ISIS’s tactics.

Their latest depraved strategy is turning kidnapped children into suicide bombers. Just last year, three girls strapped with explosives walked into a refugee camp. Two set off their explosives, killing 60 people. The third had a last minute change of heart after recognizing her parents in the camp. There were 151 suicide attacks in the Lake Chad region last year, according to a recent UNICEF report. One in five bombers were children, and 75 percent of those children were girls, UNICEF said.

Other young women and girls are forced to marry Boko fighters and bare their children.

“What does one say — you’re a 14-year-old girl, you’re in your village, these guys show up and says, ‘Hey I have a choice for you. I am going to kill you or you can marry me,” Power said. “She feels that that was a choice. That wasn’t a choice. They didn’t give her a choice.”

The top Nigerian general in charge of the Multi-National Joint Task Force tells us they’ve found crude explosives in bicycles, baskets, even strapped to birds. Some of the girls, he says, are being drugged before their missions with an opioid called Tramadol.

The fallout of the terror campaign is evident at Minawao refugee camp in Northern Cameroon. We hear heartbreaking stories of husbands slaughtered, children escaping Boko Haram and trekking for days, then starving in the Sambisa forest for months as they hid from Boko fighters. In the camps, we see UN agencies like WFP, UNHCR and UNICEF aiding and teaching 58,000 displaced people, USAID and NGOs like Oxfam, Médecins Sans Frontières (MSF), World Food Programme and International Rescue Committee (IRC) working to alleviate the deprivation.

Every chance we get, we leave the diplomatic security bubble and travel into refugee camps on our own. There, a painful pattern soon emerges: Beyond sexual slavery, we heard accounts of villages being burned to the ground and forced religious conversions.

One woman recounted how the Boko fighters told her they were commanded to kill all Christians carrying Bibles.

It’s the echo of their lilting voices telling us horror stories of senseless killings that lingers in my memory.

Another beautiful young woman, Harjare Kumenggar, said six Boko fighters surrounded her father, grabbed his dagger from his hands, slit his throat and sliced out his tongue in front of her. She was just 18 years old. She said they stole his motorcycle and kidnapped her two younger siblings. She told us one of the attackers, who was from her village, intervened to save her.

Now 20 years old, Harjare has been living in an IDP (internally displaced person) camp outside the Nigerian capital of Abuja. When I asked her for a favorite memory of her father, who was a successful farmer, she said he wanted her to get an education, but now that he’s gone, her uncles wanted her to get married. Just out of her teens, but her education came to an abrupt end.

We arranged for two other women, witnesses to Boko atrocities, to be brought down from Nigeria’s largely Muslim, far northern Borno region through three hours of checkpoints to meet us in Yola, Nigeria. They had returned to their villages after being taken by Boko Haram fighters.

One woman, wearing a white hijab, described seeing bomb-making materials in the forest. She said the fighters did not let the women see the process, but she saw jugs of kerosene. She said she also heard the children being told that becoming a suicide bomber is a “direct path to God.”

The other woman, Mariam Saidu, says she was kidnapped along with her six kids, put on a truck and kept in the encampment, where they were held captive in the Sambisa forest for nearly a year. She said they had to take husks of corn, grind it up and try to make a meal out of nothing. And some days, she said, there was nothing.

She tells us with little emotion on her face that two of her six children withered away and died in that forest.

But she’s one of the lucky ones to have survived. She says when one woman refused to marry a Boko fighter, she saw them shave her head, then slit her throat.

Mariam said her friend, Husaina, who was held captive along with hundreds of others, was forced to marry a fighter. She became his fourth wife. The four wives, Mariam said, slept in one room. When the solider wanted to have sex, they would go out to the bush where he would rape her and they would sleep on a mat under a tree with him. She said Boko fighters like to sleep outside for security.

Mariam ran when another fighter told her he wanted to take her for his wife. She was already married, and made plans to run for it that night with her kids.

Finally, she said her friend Husaina, managed to escape as well, and returned home recently. She was seven months pregnant. Mariam says the two friends were happy to be reunited and that Husaina “was laughing, but not laughing on the inside.” The two had agreed to come down to Yola to meet us, but Husaina went into labor last week and died giving birth to her Boko captor’s baby.

Mariam says people call him the “Boko baby.” His given name is “Mohammed.”

To watch the video, click here