How Do You Start A genocide?

On the morning of April 7th 1994, orders went out across Rwanda. The interahamwe militia set up roadblocks around Kigali, opposition leaders were murdered and soldiers and militia were sent throughout the country to carry out a wave of killings.

The early organisers included politicians, military leaders, businessmen, local mayors and police. But quickly thousands of ordinary people – shopkeepers, teachers and farmers – were encouraged or harassed into joining the killing. Machetes were familiar tools in a country of small farmers. In 1993 the Rwandan government had imported $750,000 worth of new machetes from China.

The killings spread throughout Rwanda, though at different speed in different areas. In some places, the militia were transported in from other regions and, working from carefully prepared lists, swept through neighbourhoods targeting Tutsis and moderate Hutus. But Rwanda is a small country, and in many places there was no need for lists.

The killers knew their victims personally

“Rwanda, famous land of a thousand hills, is above all a land of one vast village. Four out of five Rwandan families live in the countryside…. Even Kigali seems less like a capital city than a collection of villages linked by little valleys and tracts of open ground.

After the genocide, many foreigners wondered how the huge number of Hutu killers recognized their Tutsi victims in the upheaval of the massacres, since Rwandans of both ethnic groups speak the same language with no distinctive differences, live in the same places, and are not always physically recognizable by distinctive characteristics.

The answer is simple. The killers did not have to pick out their victims: they knew them personally. Everyone knows everything in a village.”

From A time for machetes. The killers speak by Jean Hatzfeld

Looking for safe places

Tutsis spontaneously moved to where they thought they would be safest – schools, churches and villages with a high Tutsi population. Government radio also told them to take refuge in these places, but in reality they were being rounded up. It was much easier to kill a large group trapped in one area than to chase individuals through villages, forests and marshes.

Where they resisted, the Rwandan army was trucked in with machine guns and grenades. Within two weeks, perhaps a quarter of a million people had been slaughtered.

Outstandingly effective murder

“In the land of philosophy that was Germany, genocide was intended to purify being and thought. In the rural land of Rwanda, genocide was meant to purify the earth, to cleanse it of its cockroach farmers. The Tutsi genocide was thus both a neighbourhood genocide and an agricultural genocide. And in spite of its summary organization and archaic tools, it was outstandingly effective.

Its yield proved distinctly superior to that of the Jewish and Gypsy genocide, since about 800,000 Tutsis were killed in twelve weeks. In 1942, at the height of the shootings and deportations, the Nazi regime and its zealous administration, its chemical industry, its army and police, equipped with sophisticated material and industrial techniques (heavy machine guns, railway infrastructure, index files, carbon monoxide gas trucks, Zyklon B gas chambers…) never attained so murderous a performance level anywhere in Germany or its fifteen occupied countries.” (Jean Hatzfeld)

The foreigners are leaving

Within a few hours, foreigners were leaving Rwanda in large numbers.

From offices, embassies, NGOs, monasteries and universities, road convoys headed for neighbouring countries. Some left by an emergency airlift. Their sudden departure was a surprise to many Rwandans, and it had an immediate effect on both victims and killers.

The UN comes… and goes

“A detachment of blue-helmeted UN soldiers in three armoured vehicles arrived in the little town (of Nyamata), visiting the church, the convent, and the maternity and general hospitals. At each stop they picked up whites – five priests and three nuns in all. Mission accomplished, the convoy turned around and swiftly vanished down the main street.

Valerie Nyirarudodo, a nurse-midwife at the Sainte-Marthe Maternity Hospital, remembers, “They pulled up in front of the gate. They told the three white sisters to pack small bags immediately. They said, ‘No point anymore in wasting time with goodbyes, right now is goodbye.’ The Swiss women asked to bring along their Tutsi colleagues in white caps. The soldiers replied, ‘No, they are Rwandan, their place is here. It is better to leave them among their brothers and sisters.’ The convoy left, followed by a van of singing interahamwe.

Of course, soon afterwards, the Tutsi sisters were cut just like the others.”

from A Time for Machetes: the Killers Speak by Jean Hatzfeld

Claudine Kayitesi. Farmer and survivor

No-one will stop us

INNOCENT RWILILIZA, a survivor, witnessed the passage of the armoured cars: “They caused a big panic among the interahamwe who were already roving in the streets, heating themselves up with sudden bursts of gunfire. Some of them shouted, ‘The whites are here, others will come, they have terrible weapons, it’s all over for us!’

When they saw the convoy disappear in the dust without even a little stop for curiosity or a drink on the main street, they celebrated with some Primus and shot off the cartridges in their guns as a sign of relief. You could see they felt saved. They were rid of the last stumbling block, so to speak.”

ADALBERT (a killer): “Ever since the plane crash, the radio had hammered at us, “The foreigners are departing… this time they are showing no interest in the fate of the Tutsis. We witnessed that flight of the armoured cars with our own eyes. For the first time ever, we did not feel we were under the frowning supervision of the whites.”

From A time for machetes. The killers speak by Jean Hatzfeld

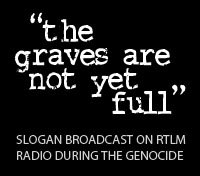

Hate radio

Anti-Tutsi articles and graphic cartoons began appearing in the Kangura newspaper from around 1990.

In June 1993 a new radio station called Radio-Television Libre des Mille Collines (RTLMC) began broadcasting in Rwanda…

The station was rowdy and used street language – there were disc jockeys, pop music and phone-ins. Sometimes the announcers were drunk. It was designed to appeal to the unemployed, the delinquents and the gangs of thugs in the militia. “In a largely illiterate population, the radio station soon had a very large audience who found it immensely entertaining.” (Linda Melvern)

The U.S. – “We believe in freedom of speech”

Some people – including the Belgian ambassador and staff of several aid agencies – recognised the danger and asked for international help in shutting down the broadcasts, but it was impossible to persuade western diplomats to take it seriously. They dismissed the station as a joke.

David Rawson, the US ambassador, said that its euphemisms were open to interpretation. The US, he said, believed in freedom of speech.

The radio told people to go to work and everyone knew that meant get your machete and kill Tutsis.

based on information in A People Betrayed by Linda Melvern

Who was behind the radio station?

RTLM was set up and financed by hard-line Hutu extremists, mostly from northern Rwanda: wealthy businessmen, government ministers and various relatives of the President. Its backers also included the directors of two African banks and the vice-president of the interahamwe (militia).

Roadblocks

“I can only remember the face of one man. He had wild matted hair, his eyes were red, and he reeked of beer and old sweat.

He scowled at Plate and then slowly moved his barricade of beer crates. Tony’s voice hissed in my ear again: ‘Can you just imagine what it’s like to be a Tutsi coming up against a roadblock with the likes of that bastard on it?’

I couldn’t imagine what it would be like. The stomach-churning fear and then, as your identity card was seized, the certainty of death. In the preceding weeks tens of thousands of Tutsis had spent their last moments of life at such roadblocks.”

The singling out… the humiliation

I remembered the stories of what happened to Tutsis at the roadblocks on this road. The singling out, the beating and humiliation and then the killing. Women who were seized at these barricades were frequently raped before being murdered. I knew that somewhere near each of these barriers there was a mass grave, perhaps several graves holding the bodies of the local Tutsi population.

A pathological hatred

“These men really did believe that they were about to be returned to the dark ages of Tutsi autocracy. All the stories of oppression and humiliation that had been handed down from their parents, all the conspiracy theories of the government, and all the fear caused by the RPF incursions since 1990 had been whipped up by extremist politicians to produce a pathological hatred of the Tutsis. I asked one of the men what would happen if a Tutsi came up to the roadblock. He simply smiled.

They eventually waved us on our way with handshakes and smiles. I did not know what to feel about them. Revulsion at their warped psychology certainly. But also pity. These were people who lived in wretched poverty, who had been recruited to do the fighting and killing for people who were now safely in exile.

Very soon the RPF would come and rout this rabble, either killing them or driving them into exile. The knowledge that they had almost certainly been part of the genocide prevented too deep a sense of pity. But I could not help feeling that they were the lesser part of the evil that had been unleashed.”

from Seasons of Blood: a Rwandan Journey by Fergal Keane

Images are screengrabs from the film Shake hands with the devil. The journey of Romeo Dallaire

The difference between life and death

“We tried to run together in small teams, to inspire courage in one another. He who was surprised in an ambush, was killed; he who twisted his ankle, was killed; he who was caught by fever or diarrhoea, was killed. Every evening, the forest was strewn with dozens of the dead and dying.”

Innocent Rwililiza, 38 year old teacher, Nyamata

Saved by beer

“Many foreign journalists say that beer and such things played a decisive role in the killings. This is correct, but in a way completely different to how they imagined it. In a certain way, many amongst us owe our survival to Primus and we should thank it.

The killers would turn up sober in the morning to start killing. But in the evening they would empty more Primuses than usual, to reward themselves, and that would soften them up for the next day.

The more they killed, the more they stole, the more they drank. Perhaps to relax, to forget, or to congratulate themselves. In any case, the more they drank in the evening, the more their schedule was delayed. Without a doubt it is such trifles that saved us.”

Innocent Rwililiza From The survivors speak by Jean Hatzfeld

Don’t eat the fish

Edward saw bodies in the river on the way to Kigali. ‘There is lots of them,’ he says. When children try to sell us fish, Edward says not to eat them.

They come from Lake Victoria and the fish are said to be feeding on corpses. ‘Not nice to eat, bad luck to eat,’ he says, smiling.

from Season of Blood.A Rwandan Journey

by Fergal Keane

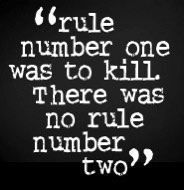

A simple plan

“The first day, a messenger from the municipal judge went house to house summoning us to a meeting right away. There the judge announced that the reason for the meeting was the killing of every Tutsi without exception. It was simply said, and it was simple to understand.

So the only questions were about the details of the operation. For example, how and when we had to begin, since we were not used to this activity, and where to begin, too, since the Tutsis had run off in all directions. There were even some guys who asked if there were any priorities.

The judge answered sternly: “There is no need to ask how to begin. The only worthwhile plan is to start straight ahead into the bush, and right now, without hanging back anymore behind questions.”

From A time for machetes. The killers speak by Jean HatzfeldPancrace

Rule number one was to kill. There was no rule number two. It was an organisation without complications.”

Pancrace

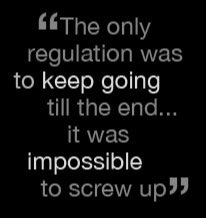

“The plane came down April 6. A very small number of local Hutus went straight for retaliation. But most waited four days in their houses and in the nearest cabarets, listening to the radio, watching Tutsis flee, chatting and joking without planning a thing.

On April 10 the burgomaster (mayor) in a pressed suit and all the authorities gathered us together. They lectured us, they threatened in advance anyone who bungled the job, and the killings began without much planning.

The only regulation was to keep going till the end, maintain a satisfactory pace, spare no one, and loot what we found. It was impossible to screw up.”

Jean Baptiste

a final plan: just kill Tutsis

“On April 11 the municipal judge in Kibungo sent his messengers to gather the Hutus up there. Lots of interahamwe had arrived in trucks and buses, all jostling and honking on the roads. It was like a city traffic jam.

The judge told everyone there that from then on we were to do nothing but kill Tutsis. Well, we understood: that was a final plan. The atmosphere had changed.

That day misinformed guys had come to the meeting without bringing a machete or some other cutting tool. The interahamwe lectured them: they said it would pass this once but had better not happen twice. They told them to arm themselves with branches and stones, to form barriers at the rear to cut off any escaping fugitives. Afterwards everyone wound up a leader or a follower, but nobody ever forgot his machete again.”

Fulgence

“Killing is very discouraging if you yourself must decide to do it, even to an animal. But if you must obey the orders of the authorities, if you have been properly prepared, if you feel yourself pushed and pulled, if you see that the killing will be total and without disastrous consequences for yourself, you feel soothed and reassured. You go off to it with no more worry.”

Pancrace From A time for machetes. The killers speak by Jean Hatzfeld

The blade has nothing to say

ELIE: The club is more crushing, but the machete is more natural. The Rwandan is accustomed to the machete from childhood. Grab a machete – that is what we do every morning. We cut sorghum, we prune banana trees, we hack out vines, we kill chickens.

Even women and little girls borrow the machete for small tasks, like chopping firewood. Whatever the job, the same gesture always comes smoothly to our hands. The blade, when you use it to cut branch, animal, or man, it has nothing to say.

In the end, a man is like an animal: you give him a whack on the head or the neck and down he goes. Only young guys used clubs. The club has no use in agriculture, but it was better suited to their way of trying to stand out, of strutting in the crowd. Same thing for spear and bows: those who still had them could find it entertaining to lend them or show them off.

More productive than farming

IGNACE: Killing could certainly be thirsty work, draining and often disgusting. Still it was more productive than raising crops, especially for someone with a meagre plot of land or barren soil.

During the killings anyone with strong arms brought home as much as a merchant of quality. We could no longer count the panels of sheet metal we were piling up. The taxmen ignored us. The women were satisfied with everything they brought in. They stopped complaining.

For the simplest farmers, it was refreshing to leave the hoe in the yard. We got rich, we went to bed with full bellies, we lived a life of plenty. Pillaging is more worthwhile than harvesting, because it profits everyone equally.

“That time greatly improved our lives since we profited from everything we’d never had before. The daily beer, the beef, the bikes, the radios, the sheet metal, the windows, everything. People said it was a lucky season, and that there would not be another.”

A day’s work

PIO: We would wake up at six o’clock. We ate brochettes of grilled meat and nourishing food because of all the running we had to do. We met up in town, near the shops, and chatted with pals along the way to the soccer field. There they would give us orders about the killings and our itineraries for the day, and off we went, beating the bush, working our way down to the marshes. We formed a line to wade into the mud and the papyrus. Then we broke up into small bands of friends or acquaintances.

We got on fine, except for the days when there was a huge fuss, when interahamwe reinforcements came in from the surrounding areas in motor vehicles to lead the bigger operations. Because those young hot-heads ran us ragged on the job.

Looting on the way home

LEOPORD: We began the day by killing, we ended the day by looting. It was the rule to kill going out and to loot coming back.

We killed in teams, but we looted every man for himself or in small groups of friends – except for drinks and cows, which we enjoyed sharing. And the plots of land, of course, they were discussed with the organisers. As district leader, I had got a huge fertile plot, which I counted on planting when it was all over.

Anyone who couldn’t loot because he had to be absent, or because he felt too tired from all he had done, could send his wife. You would see wives rummaging through houses. They ventured even into the marshes to get the belongings of the unfortunate women who had just been killed.

People would steal anything – bowls, pieces of cloth, jugs, religious images, wedding pictures – from anywhere, from the houses, from the schools, from the dead.

Quotes on this page from A time for machetes. The killers speak by Jean Hatzfeld. Images by Dave Fullerton

With me, he behaved nicely

“He came home often. He never carried a weapon, not even his machete. I knew he was a leader, I knew the Hutus were out there cutting Tutsis.

With me, he behaved nicely. He made sure we had everything we needed. Actually, he was steeped in bad politics but not in bad thoughts. He was gentle with the children. I did not want to ask him about the trouble that was spreading everywhere. To me, he was the nice man I married.” (Marie Chantal, talking about her husband, a killer)

We were ordinary

ALPHONSE: “Some offenders claim that we changed into wild animals, that we were blinded by ferocity, that we buried our civilization under branches, and that’s why we are unable to find the right words to talk properly about it.

That is a trick to sidetrack the truth. I can say this: outside the marshes, our lives seemed quite ordinary… we soaped off our bloodstains in the basin, and our noses enjoyed the aromas of full cooking pots. We rejoiced in the new life about to begin by feasting on leg of veal. We were hot at night atop our wives, and we scolded our rowdy children. Although no longer willing to feel pity, we were still greedy for good feelings. We went about all sorts of human business without a care in the world – provided we concentrated on killing during the day, naturally.

At the end of that season in the marshes, we were so disappointed we had failed. We were disheartened by what we were going to lose, and truly frightened by the misfortune and vengeance reaching out for us. But deep down, we were not tired of anything.”

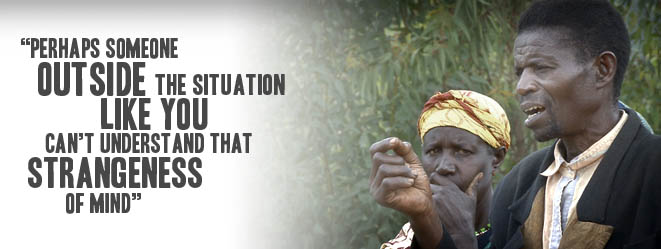

I don’t recognise me

PIO: We no longer saw a human being when we turned up a Tutsi in the swamps. I mean a person like us, sharing similar thoughts and feelings.

It is as if I had let another individual take on my own living appearance… This killer was indeed me, but he is a stranger to me in his ferocity. I admit and recognise my obedience at that time, my victims, my fault, but I fail to recognise the wickedness of the one who raced through the marshes on my legs, carrying my machete.

The most serious changes in my body were my invisible parts, such as the soul or the feelings that go with it. I do not recognise myself in that man. But perhaps someone outside this situation, like you, cannot have an inkling of that strangeness of mind.

Dangerously fired up

JEAN BAPTISTE: The more we killed, the more greediness urged us on. Greediness – if left unpunished, it never lets you go. You could see it in our eyes bugged out by the killings. It was even dangersome. There were those who came back in bloodstained shirts, brandishing their machetes, shrieking like madmen, saying they wanted to grab everything. We had to calm them with drinks and soothing words. Because they could turn ugly for those around them.

Quotes on this page from A time for machetes. The killers speak by Jean Hatzfeld. Images by Dave Fullerton

Each to his own personality

“Some hunted like grazing goats, others like wild beasts. Some hunted slowly because they were afraid, some because they were lazy.

Some struck slowly from wickedness, some struck quickly so as to finish up and go home early to do something else. It was each to his own technique and personality.

Me, because I was older, I was excused from trudging around the marshes. My duty was to patrol in stealth through the surrounding fields. I chose the ancestral method, with bow and arrows, to skewer a few Tutsis passing through. As an old-timer, I had known such watchful hunting since my childhood.” (Ignace)

Working with the tools you have

“The fumblers were followed as a precaution, because of possible incompetence. The interahamwe gave them compliments or reprimands. Sometimes, if they wanted to be strict, the penalty was to finish off the wounded person, whatever it took. The culprit had to keep tackling the job to the end. The worst thing was being forced to do this in front of your own colleagues.

We were only a few, at the very start. That didn’t last long, thanks to our familiarity with the machete in the fields. It’s only natural. If you and me are given a ballpoint pen, you will prove more at ease with writing work than me, no jealousy on my part. For us, the machete was what we knew how to use and sharpen. Also, for the authorities, it was less expensive than guns. Therefore we learned to do the job with the basic instrument we had.” (Fulgence)

Choir leader, killing boss

The Saturday after the plane crash was the usual choir rehearsal day at the church. We sang hymns in good feeling with our Tutsi compatriots, our voices still blending in chorus.

On Sunday morning we returned for mass; they did not arrive. They had already fled into the bush in fear of reprisals, driving their goats and cows before them. That disappointed us greatly, especially on a Sunday. Anger hustled us outside the church door.

We left the Lord and our prayers inside to rush home. We changed from our Sunday best into our workaday clothes, we grabbed clubs and machetes, we went straight off to killing.

In the marshes, I was appointed killing boss because I gave orders intensely. Same thing in the Congolese camps. In prison I was appointed charismatic leader because I sang intensely. I enjoyed the alleluias. I gladly felt rocked by those joyous verses. I was steadfast in my love of God.”

(Adalbert)

Quotes on this page from A time for machetes. The killers speak by Jean Hatzfeld. Images by Dave Fullerton

One Response

May the murdering hutus rot in hell.