IN January, Liberia’s minister of education made a far-reaching announcement, which nevertheless has largely flown under the radar – until now, when a top UN official has come out strongly in opposition to it.

Liberian education Minister George Werner announced that the entire pre-primary and primary education system would be outsourced to Bridge International Academies to manage. The deal will see the government of Liberia pay over $65 million over a five-year period; public funding for education will support services subcontracted to the private, for-profit, US-based company.

Under the public-private arrangement, the company will design curriculum materials from April to September 2017, while phase two will have the company rollout mass implementation over 5 years, “with government exit possible each year dependent on provided performance from September 2017 onwards,” the report from Liberia’s FrontPage Newspaper said.

“Eventually the Ministry of Education is aiming to contract out all primary and early childhood education schools to private providers who meet the required standards over 5 year period,” the article states.

It would possibly be the largest, and most ambitious privatisation attempt in Africa’s recent history, and the move has elicited mixed reactions, for good reason.

The UN’s Special Rapporteur on the right to education, Kishore Singh, last week described it as “unprecedented at the scale currently being proposed and violates Liberia’s legal and moral obligations.”

The UN official and human rights expert noted that provision of public education of good quality is a core function of the State.

“Abandoning this to the commercial benefit of a private company constitutes a gross violation of the right to education,” said Singh.

Mail & Guardian Africa breaks down the issue, and its wide-reaching implications, and why Africa should sit up and pay attention to this “education innovation” company that has roots in Silicon Valley.

What is Bridge International Academies?

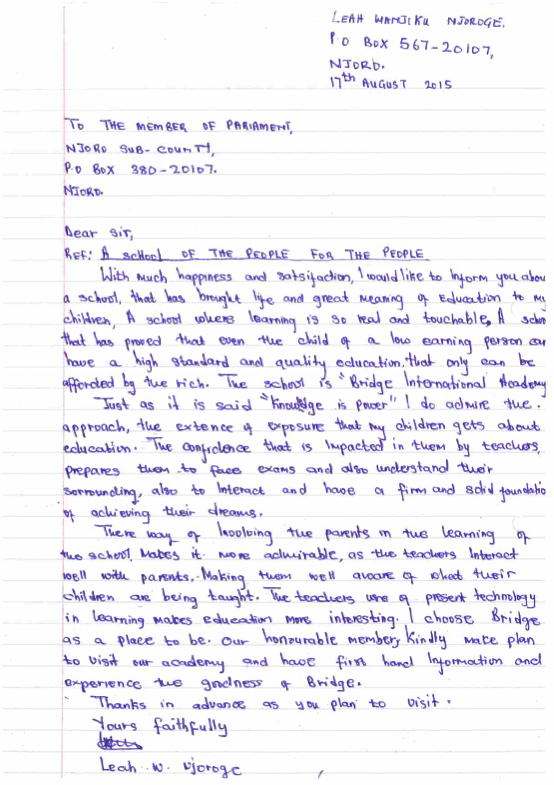

By their own description, Bridge is the world’s largest education innovation company, with 100,000 students in its 400+ networked schools so far, mostly in Kenya and Uganda; it plans to educate 10 million children across a dozen countries in Africa and Asia by 2025, specifically targeting low-income families.

What is the Bridge model of delivery?

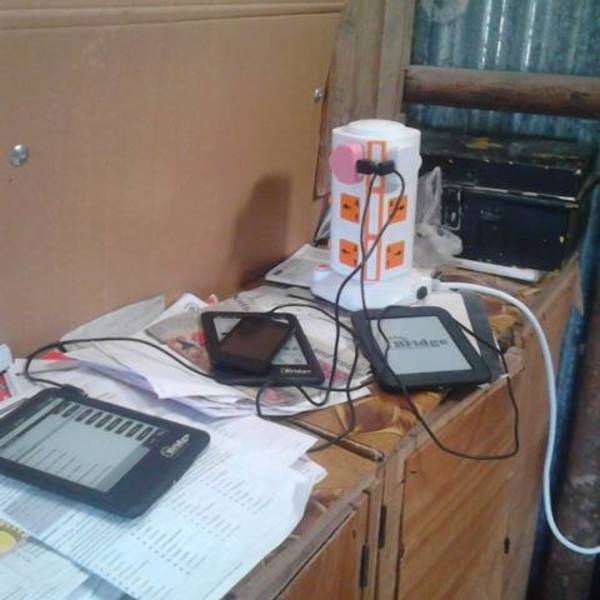

Bridge’s model is “school in a box” – a highly structured, technology-driven model that relies on teachers reading standardised lessons from hand-held tablet computers. Bridge hires education experts to script the lessons, but the teacher’s role is to deliver that content to the class. This allows Bridge to hold down costs because it can hire teachers who don’t have college degrees – a teacher is only required to go through a five-week training programme on how to read and deliver the script.

To keep tuition costs low – about $6 a term – Bridge depends on large class sizes. An ideal class size is 40 to 50 pupils, but the classes can get upward of 70 students. The physical infrastructure is modest too – often just simple building made of sheet metal and timber, which can be constructed in a few days.

But the back-end – the technology running it all – is sophisticated indeed, relying on Big Data, algorithms, and automation of most school administrative tasks. Bridge says that this model gives poor families an option to get “quality education for their children for a modest fee”, in an environment where free government schools are often overcrowded, understaffed and ineffective.

The company says its students have better grades, gaining an additional .34 standard deviation on core reading skills and an additional .51 standard deviation on maths compared to their peers in neighboring schools, “based on USAID-designed exams administered by an independent monitoring and evaluation company – translating into over 250 additional days of learning.”

What are the objections to Bridge, and why do they matter?

1. Teachers are robots that just read scripts off hand-held tablets, and tha’s not the best way for children to learn – it discourages student interaction both with the teacher and with each other, suppresses critical thinking, and encourages rote learning. Teacher unions in the region have come out hard against the company, arguing that it will discourage the employment of qualified teachers.

Bridge says that given the alternatives – which include government schools staffed by unmotivated teachers and other non-formal schools offering little in-house teacher training – the private school chain offers an education that’s more accountable, and subject to rigorous testing and review.

In any case, under the traditional model, what a child is able to learn is “always limited by what the teacher knows, so you can never have the child leap-frog previous problems within that town, city or country,” according to Bridge co-founder Shannon May.

2. Tuition fees are actually not cheap – $6 a term is prohibitive for most poor families, as often they have more than one school-going child. A joint statement from several civil society organisations in Kenya and Uganda opposing Bridge says that for the poorest half of Kenyan households who earn Ksh7,000 ($70) or less per month, sending three children to a Bridge Academy would cost at least 24% of their monthly income.

“Taking into account more realistic monthly costs of $17 that include school meals, the proportion rises to at least 68% of their monthly income,” the statement says.

3. Bridge’s claim that its students do better than their comparable peers at government schools seems to be from a study commissioned by the company itself, the joint civil society statement said that it was “not aware of any independent academic study available on Bridge Academies.”

4. On a broader scale, critics say, Bridge is undermining the public education system by diverting off children from the most motivated families – the ones who are poor, but have enough to pay $6 a term. These are the ones who care enough about education to put their money down, and so could be the ones holding government schools accountable. But one could also argue that keeping everyone in the public school system may not necessarily improve things – it may only result in lousy outcomes for all.

5. Mass privatisation of the education system, as Liberia is attempting, is an anathema and just wrong – no matter the positive outcomes in better grades. Provision of public education of good quality is a core function of the State, and an essential public service. Outsourcing this to the commercial benefit of a private company is a gross violation of the right to education, and a country’s international obligations, as the UN special rapporteur on education described it.

Best testing ground

In any case, Liberia might be the best country in Africa to “test” this model. The education system is still in shambles following a prolonged and brutally destructive 14-year civil war, resulted in the flight, or death, of a large chunk of trained workforce, physical infrastructure was destroyed. The Ebola outbreak of 2014-2015 just set everything back again, and Liberia is significantly behind most other countries in the African region in nearly all education statistics.

In that case, an education system, which is modelled on accountability, standardisation, analytical rigour, and policy changes that can be backed with rich data sets – albeit private – is far better than what Liberia has at the moment.

Still, it sets the teeth of many on edge. And the claim that Bridge gives parents a choice ceases to hold water in Liberia, where every public school may soon become a Bridge International Academy.

UPDATE: An earlier version of this story indicated that parents in Liberia would be paying $6 as tuition fees for each child, and that this could exclude parents who don’t come up with the money. Bridge International Academies has informed Mail & Guardian Africa that the education model in Liberia would not be paid for by parents out-of-pocket, but that it would be financed by public funds from the government of Liberia.