![Elizabeth Nyanyot Diu was married off when she was 12 years old [Caitlin McGee/Al Jazeera]](http://abovewhispers.com/wp-content/uploads/2016/02/South-Sudan-Child-Marriage-3.jpg)

At 12, she was told she had to marry a 30-year-old man who beat her regularly. “At any time, whenever he wanted, he would cane me,” she remembers.

Two years into their union, she became pregnant but there were complications. Her body wasn’t ready to carry and give birth. “It nearly killed me,” she said.

“My first-born died because I was too young. I was just 14 years old …. Women are having children too young,” Diu added.

Early and forced marriages are widespread in South Sudan.

Even before the start of the civil war in December 2013, UNICEF reported that 52 percent of all girls were married under the age of 18. Now, after two years of persistent fighting and violent attacks, the situation is getting worse, according to the organisation.

“One of the trends that we have seen in the past two years is an increasing number of girls forced into early marriage,” said Ettie Higgins, UNICEF’s deputy representative for South Sudan.

The civil war that started in December 2013 has been disastrous for South Sudan.

It has killed tens of thousands of people, displaced 1.69 million and left more than two million people facing severe hunger. But the toll on women has been particularly horrific.

During her visit in July 2014, the UN special envoy for sexual violence in conflict areas, Zainab Hawa Bangura, said women in South Sudan were the victims of the worst sexual violence she had ever seen. Bangura described the levels of assault as “rampant”.

According to a Human Rights Watch report from September, there has been a surge in sexual attacks and violence since the start of the civil war.

Dina Hunaiti manages the Women’s Protection and Empowerment programme run by the International Rescue Committee in the town of Nyal in Unity state.

She said violence against women had reached epidemic proportions.

“It is entrenched,” she explained. “It is expected as a normal part of a relationship and a normal part of life.”

Hunaiti said she saw a lot of forced marriage cases. “There are a lot of instances where girls are forced to get married. Not just early marriage but forced marriage ….”

Only 35 percent of girls in South Sudan get an education.

“I’ve worked in places before where the early marriage isn’t such an issue for girls because of how they have been raised,” said Hunaiti. “But here the girls actually want to stay in school.”

Higgins said a lack of money was one of the factors that drives families to pull their daughters out of school and marry them off.

While girls are often the most vulnerable in conflict zones, the increase in early and forced marriages is also happening in areas where there is no fighting.

“We’ve seen it used as a negative coping mechanism by families … to marry off a daughter means they have one less mouth to feed in the family,” Higgins said.

“It’s part of the tough economic climate and families think they can benefit economically by forcing their girls into this kind of marriage.”

In exchange for giving away their daughters to marriage, families receive a dowry. In most cases this takes the form of cattle.

“I was forced into the marriage young because of the dowry,” Elizabeth said. Her family wanted to marry her off young because she would be worth more cows, she explained.

![Women in South Sudan are the victims of extreme sexual violence, according to UN officials [Caitlin McGee/Al Jazeera]](http://abovewhispers.com/wp-content/uploads/2016/02/South-Sudan-Child-Marriage-1.jpg)

For many of these girls, these unions have deadly or debilitating consequences.

South Sudan has the highest rate of maternal mortality in the world, according to World Vision. Girls in South Sudan are three times more likely to die in childbirth than they are to finish high school.

Mi Hao Sito is a midwife for Doctors Without Borders, based in the northwest city of Aweil.

She sees girls in their early teens suffering through an obstructed labour because their bodies aren’t physically mature enough to cope with delivering a baby.

“Sometimes by the time they get to us they have been in labour for two days and the baby is already dead,” she said. “This is happening to girls who are 14, 15, 16 years old. They are too young to get married, it is too early for their bodies to be having a baby.”

Sito said early and forced marriages were a big part of why so many girls die while giving birth in South Sudan.

“Young girls’ bodies are not mature enough and mentally they’re not mature enough as well. They are still kids. It’s too much physically and mentally. I think they want to go to school but they cannot go,” Sito explained.

Many of those who do survive are left with a debilitating condition called fistula.

It can occur when the baby is stuck for so long during childbirth that there is rip between the vagina and the bladder or the rectum.

It leaves women unable to control their bladder or bowel or both. So when they stand up, the urine drains out of them. The stigma and the shame associated with fistula means many women stay shut away and marooned in their villages.

Corrective surgery is available, but in many cases it is a recurring problem.

“After surgery there is a strict recovery period that requires them to not get pregnant straight away,” said Sito. But many women have little control over their pregnancies and often find themselves pregnant soon after. “And then when they go into labour, they try and have the baby at home again instead of coming to hospital … and then they get fistula again.”

Many of the young women understand that they need to come to hospital, Sito said, but they face pressure from their families and husbands to get pregnant again quickly and to stay at home to have the baby.

![Local women often feel disempowered by the social expectations surrounding them [Caitlin McGee/Al Jazeera]](http://abovewhispers.com/wp-content/uploads/2016/02/South-Sudan-child-marriage.jpg)

Now 45, Elizabeth is taking part in the Women’s Empowerment and Protection programme run by the International Rescue Committee in Nyal in Unity state. It enables a group of women to meet once a week to talk and make crafts that they can take home and sell.

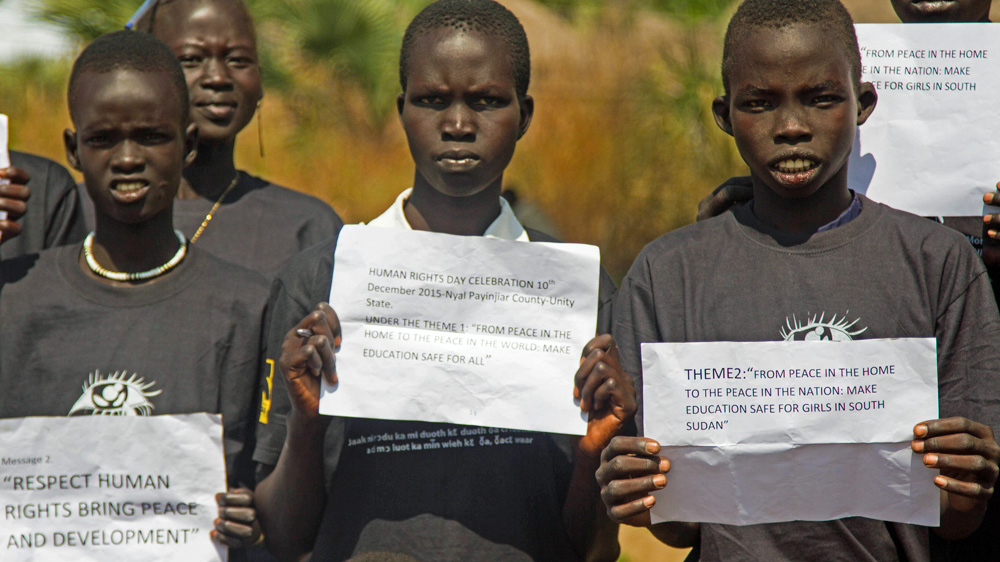

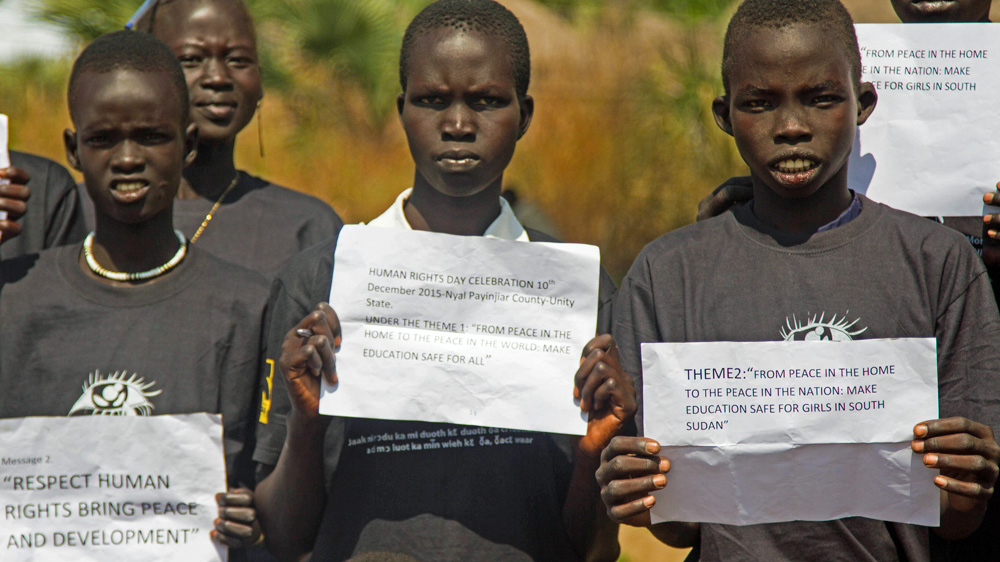

Another aspect of the programme is to educate boys at the local school about women’s rights.

Peter Kam is a teacher at Nyal mixed Primary school. He said that since the IRC’s Women’s Protection and Empowerment programme started last year, there have been big changes in the playground.

“I’ve seen the attitudes of some families change,” Kam said. “Now families are understanding that if their girls can go to school then they can get jobs and bring money into the family that way, instead of getting married for dowry.”

He said that before 2014 a lot of girls were being taken out of his classes and out of school to get married but now that is changing. And there is a big push to educate boys about equality.

Elizabeth believes this is the best way to break the practice of early and forced marriages.

“Men are the solution,” she said. “If they are taught then it can go into their heart and into their head.”