Balaraba Ramat Yakubu was 12 years old when she was married off. By 19 she was divorced, jilted by her husband; left to fend for herself in Kano state, northern Nigeria.

But this isn’t a sad story.

Instead it’s one of community and independence — from the unlikeliest source.

Yakubu began writing. And writing. And writing. The subject she chose was strangely fitting for this child marriage survivor: romance.

Soon entire novels emerged. Written and printed in her native Hausa language, they spurred on a whole literary subgenre — “Littattafan Soyayya” (love literature) — which years later has grown into a prosperous cottage industry for the women of Kano.

Kano’s ‘most subversive’ author

New York-based photographer Glenna Gordon has extensively documented this invisible industry in new book “Diagram of the Heart.” Working with translators, like Carmen McCain, Gordon hopes to take the blossoming local enterprise and introduce these unheard of voices from Kano to the world.

She first journeyed to the northern state with a copy of Yakubu’s most famous novel “Sin is the Puppy that Follows You Home,” recommended by a friend. The novel is one of the most accessible of the Hausa love literature; the first by a woman to be translated into English, and available on Kindle.

A couple of days into the visit, she met with Yakubu, discovering her story and the power her words have had on others.

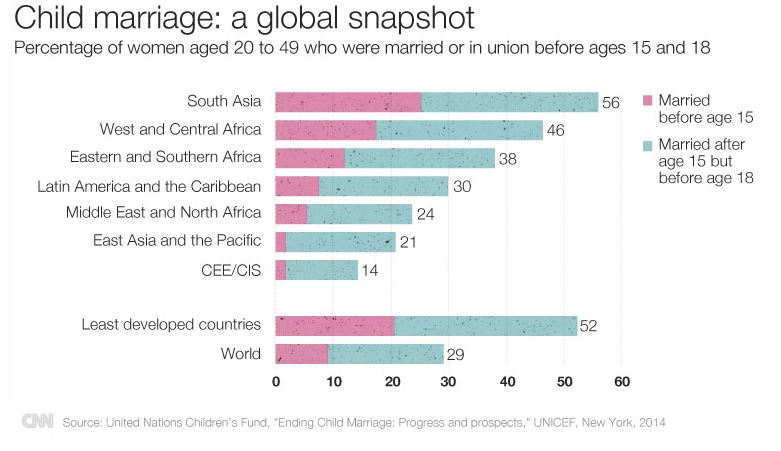

“Child marriage is a huge issue in northern Nigeria,” Gordon says. “In cities it’s less common than in the villages, but in villages and rural areas girls get married anywhere from 12 to 16.”

Yakubu has addressed the subject in her own novels, a collection Gordon describes as “the most subversive” of the genre.

In “Who will Marry an Illiterate Woman?” Yakubu addresses the subject of child marriage — and its consequences — from a female perspective. Drawing on her own experiences, Yakubu’s writing offers readers a searing condemnation of a practice that she was able to emerge from, but others might not.

Agony aunts

That’s not to say all the authors write about such serious or divisive issues.

“There’s a huge variety,” says Gordon. “Some are didactic, and speak out against human trafficking and other social issues. But then some of the books are standard romance novels, about a poor girl that gets a rich man.”

In Kano, the life of a book exists beyond its final page, with writers taking on the role of agony aunts.

“A lot of women write their phone numbers on their books,” Gordon explains. Prompted by the content of the novels, “other women call them up and ask for advice about their marriages.

“When I was hanging out with author Rabi Talle, she would have four phones, all with different numbers, and they’d be ringing constantly.”

Fighting for freedom of speech

Gordon’s photographs illustrate stacks of Hausa love literature piled up in warehouses, a testament to their popularity. And yet there are some looking to quash the genre.

In this region of Nigeria, these women are redefining their standing within Muslim society. Flirting with censorship from the morality police and working under the spectre of Boko Haram, they face bombs and book burnings.

In 2007, then-Governor of Kano state Ibrahim Shekarau publicly burned love literature books and implemented an author registration system enforced by the Hisbah, the religious police — basically, a censorship mechanism, Gordon argues.

Some authors face obstacles both publicly and privately. Behind closed doors, Gordon says there are mixed reactions to the growing number of female authors.

She explains that some writers feel pressured by husbands and families but there are others who are supported by their partners, who welcome a second source of income in a state with just over half the GDP per capita of Lagos.

Despite its following, Hausa love literature still makes up only a small fraction of Nigeria’s rich and diverse literary tradition.

Today, most Kano love literature remains untranslated, however with Yakubu pushing boundaries and new translations, Gordon hopes her new book will provide a spotlight on the burgeoning cottage industry.

She says: “(The stories are) popular in Kano, but they haven’t been heard of beyond, and (the authors) saw me as a way to make that happen, and were excited for that opportunity: to reach a bigger audience.

“They want recognition, just like everybody does.”