The internet revolution is coming – old news in much of the world but not in Chad, a tech laggard where women languish at the very back of the line when it comes to connectivity.

With just 6.5% of the population online, Chad has the 6th lowest rate of internet usage in the world, according to the latest World Bank figures.

Women are even more cut off than Chadian men as so few own phones, literacy rates are low, and cultural norms dictate that tech jobs go mostly to men, according to advocates.

But since the emergence of a handful of tech hubs, coding classes and start-up accelerators in N’Djamena, women have started breaking into the field – and are now pushing hard to ensure others are not left behind.

“Technology is something that will concern our whole lives,” said Aicha Adoum, 35, founder of a Chadian telecoms company that is working to expand internet access in the Central African country, where paved roads and electricity are rare.

“We need to sensitise young girls,” she told the Thomson Reuters Foundation.

Adoum was looked down on by family and peers when she got a job for a telecoms company because she worked at night and with men, both frowned upon.

With more women breaking into tech, this is starting to change, she said – but slowly.

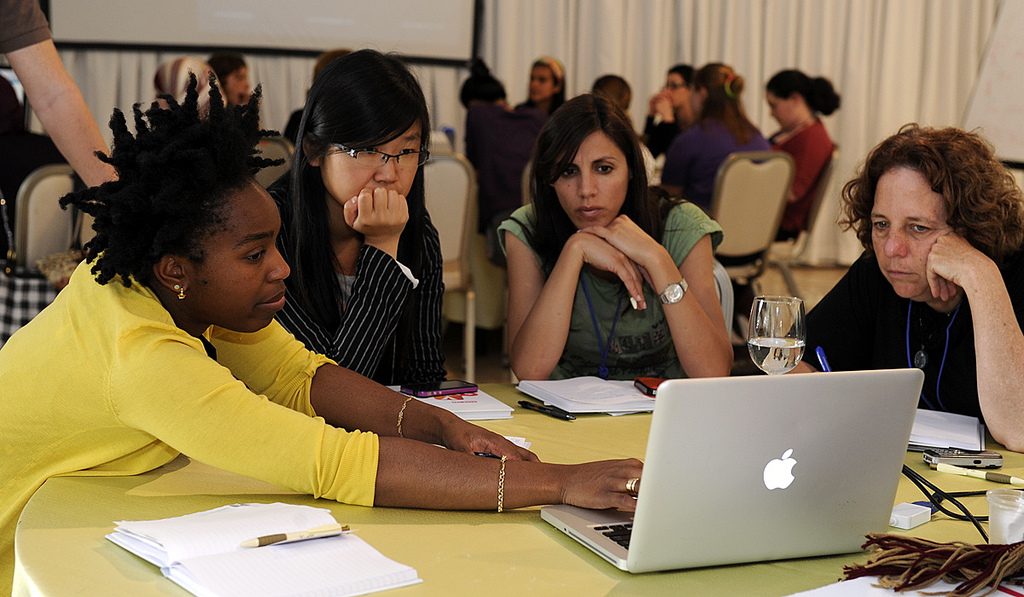

At a recent tech conference in the capital, a crowd of veiled, young women glanced around hesitantly when quizzed by a 26-year-old entrepreneur.

“Has everyone here used the internet before?” Falmata Awada asked the group, pulling up a slideshow to explain what the internet is and how it works.

Several girls shook their heads to say ‘no’ – they had never been online.

Yet all were high school or college students in the capital N’Djamena, and all had come to attend a conference on women in digital technology and entrepreneurship.

Women across sub-Saharan Africa are 15% less likely to own a mobile phone than men and 41% less likely to use mobile internet, largely due to gender gaps in income and literacy, according to the telecoms industry body GSMA.

The widest gender gaps tend to occur in poorer countries with overall lower mobile penetration, such as Chad, said GSMA.

BREAKING BARRIERS

A landlocked country in the Sahara, Chad has almost no economy beyond oil exports, while politics have been stagnant since President Idriss Deby took power in 1990.

Deby has periodically restricted internet access for political reasons, once in 2016 after a disputed presidential re-election and again in March 2018 for more than a year, forcing people to use expensive VPN services to get online.

But the number of mobile phone owners and internet users is steadily growing, and the cost of 1 GB of data fell from about $20 to $2.50 last year.

“The internet revolution is coming,” said Safia Youssouf, a software engineer and entrepreneur, telling young women to seize the opportunity as data becomes cheaper and more accessible.

The event on women in tech, called “Digit’Elle”, was part of Chad’s third annual Global Entrepreneurship Week and “Digital November”, both sponsored by foreign donors and U.N. agencies and organised by young Chadians.

Among young leaders in the field, there is a sense of optimism. Many studied abroad and returned with new ideas.

“We see that there are problems, and we know that with digital technology we can solve them,” said Awada, who studied software engineering in Senegal and returned to co-found a mobile app for pregnant women.

She received grants and opportunities through organisations such as the Tony Elumelu Foundation and Women in Africa, which Awada found out about online.

Now she wants to help other young women.

“I have the impression that most of them use the internet only for social networks – Facebook and WhatsApp,” said Awada, as some of the students at the event pulled out smartphones.

“They don’t know the other opportunities,” she said.

NOT INTERESTED

While “Digital November” was long on inspiration, some of the concrete efforts to involve women and girls fell short.

At tech hub WenakLabs, two-day digital training for high school girls was meant to include 40 students, but only nine attended. Some parents refused to let their daughters go, and some schools didn’t follow up on the offer.

“With women, it’s slightly complicated,” said WenakLabs founder Abdelsalam Safi.

“More women come in with start-up ideas in general, but they are not very interested in digital,” he said, explaining that it is seen as a male field, short on female training and support.

Several women said barriers were largely in their heads.

“Girls tell themselves it’s hard and not for them,” said 28-year-old entrepreneur Zam-zam Djorkode, who studied coding in Cameroon.

It is still widely accepted in Chad that a women’s duties are in the home, locals said.

Only 12% of Chadian girls attend secondary school, half the attendance rate of boys, according to U.N. data.

The World Bank estimates that 1% of women in the workforce have a salaried job, against 10% of men.

“As a woman, you will see your responsibilities grow every day,” Youssouf told the gathered students, referring to housework and childbearing.