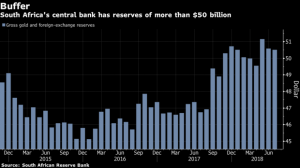

South Africa’s Lesetja Kganyago has a fight on his hands to protect the central bank’s $50 billion of reserves.

More than eight months after the ruling African National Congress decided that the South African Reserve Bank should be state-owned, like most other central banks, the governor said his main concern remains to protect the regulator’s independence and mandate.

But also at risk may be billions of dollars in reserves and a legal brawl that could last for years.

While the 97 year-old Reserve Bank’s shares are only worth about 20 million rand ($1.4 million) based on the current share price, some shareholders have argued the bank’s assets belong to them and they should be compensated for that when the government nationalizes the institution, according to Kganyago. Eight percent of its 770 owners are foreigners, so steps to nationalize could be challenged using bilateral investment treaties or end in international arbitration.

“This is not a fight I want to be busy with,” Kganyago said in an interview in his 32nd floor office in the capital, Pretoria. “There is sufficient emerging-market turmoil that keeps me busy. I should not be wasting my time on this thing.”

Photographer: Waldo Swiegers/Bloomberg

‘Paid to Go’

The rand slumped to its weakest level against the dollar in two years last month as upheaval in Turkey spilled over into other emerging markets. The currency was 0.2 percent lower at 14.7115 per dollar as of 7:16 a.m. in Johannesburg Monday.

Some of the investors do feel they are entitled to a share of the reserves, but they are wrong, said Jannie Rossouw, the head of economics and business sciences at the University of Witwatersrand. He is a former secretary at the Reserve Bank and owns its shares.

South Africa had $50.5 billion in gross reserves at the end of July and holds about 170 billion rand of deposits on behalf of the state, according to central bank data.

Some shareholders “want to be paid to go away,” Kganyago said. “‘Show me the money, show me the money!’ is what they are looking for.”

South Africa’s central bank is one of a handful, including Switzerland and Japan, still owned by private individuals. However, shareholders are limited to 10,000 shares each and have no say over monetary policy. They get to vote for seven of the central bank’s 10 non-executive directors.

“Why should we be paying people who are in any case at the moment very constrained,” Kganyago said.

Trojan Horse

Kganyago, the 52-year-old former head of the National Treasury, fought off a proposal by the nation’s anti-graft ombudsman last year to change the constitution to take away the regulator’s inflation-target mandate. Last month, the radical Economic Freedom Fighters political party, which has won support by vowing to nationalize everything from land to banks, tabled a bill to make the Reserve Bank state-owned.

If the law is passed, the change would be mainly cosmetic. That’s unless it’s used as a gateway to meddle with the mandate again, the governor warned.

“Is this a Trojan horse?” Kganyago said. “If it leads to a point that there’s that debate about the mandate of the bank and the independence of the Reserve Bank — check what happened with Turkey, check what happened in Argentina, check what happened in Venezuela. If you want an African example, check what happened in Zimbabwe.”

“Should they interfere with our independence, they’ve got a fight on their hands,” he said.

The maximum price over the past six months for a Reserve Bank share, which is available over the counter since they delisted in 2002, has been 10 rand. Investors share a maximum dividend payout of 200,000 rand a year.

‘Horrible Investment’

The stock is a “horrible investment,” according to shareholder Dawie Roodt, the chief economist at financial services company Efficient Group Ltd. He bought his shares more than two decades ago because they allow him access to the central bank’s annual meetings, where he can speak to its managers, Roodt said.

Previous governors had an acrimonious relationship with some shareholders. Tito Mboweni accused one of disrespect in 2009 when the barefoot investor dressed in lederhosen, a traditional Bavarian garment, disrupted his AGM.

During Kganyago’s four years at the helm, those gatherings have become duller affairs that last less than an hour. If the government does become the sole owner of the bank, the meetings could be over in minutes, he said.

The central bank would prefer to leave things as they are. Should nationalization take place, Kganyago won’t give up the nation’s assets or allow tinkering with the mandate.

“If there’s a dispute over these things, you can rest assured that we will have protracted fights in the courts,” he said. “Arbitration can rule either way, but the legal costs associated with that are going to be massive, there’s no doubt about that.”