Grama’s team built a machine using old car parts that can heat water without electricity. Think of the possibilities in rural parts of the developing world: Medical clinics could sterilize devices, people could clean clothes with warm water, or they could just take a hot shower, all without being connected to a grid. Revolutionary, right?

Grama took the invention to India expecting a huge response. Instead, he got: “Yeah, OK, that’s fine. But it doesn’t solve our problem.”

He had miscalculated. Rural Indians didn’t want to talk about hot water; they wanted to talk about cold milk.

“We were a classic case of a technology looking for a problem to solve,” Grama says.

“India is the largest producer and consumer of milk in the world,” he explains. “And all that has to be collected in this very time critical process, which leads to a lot of spoilage, [or] low quality milk that’s been sitting around for hours in the sun before it gets to a refrigeration facility or processing facility.”

So Grama, who grew up in Romania and moved to the United States when he was 18, set aside his award-winning solar water heater and focused on milk instead.

He moved to India and soon realized the main thing making milk go bad was unreliable power.

“The thing to understand is that all these villages do have power, [but] they don’t have it 24 hours a day.”

Sorin Grama, left, pours milk into his refrigeration system in India.

Credit:

Promethean Power Systems

Sorin Grama had a great idea. Like, a really terrific idea. It was so good, MIT awarded him one of its most prestigious entrepreneurship prizes: second place in the university’s annual 100K Entrepreneurship Competition.

Grama’s team built a machine using old car parts that can heat water without electricity. Think of the possibilities in rural parts of the developing world: Medical clinics could sterilize devices, people could clean clothes with warm water, or they could just take a hot shower, all without being connected to a grid. Revolutionary, right?

Grama took the invention to India expecting a huge response. Instead, he got: “Yeah, OK, that’s fine. But it doesn’t solve our problem.”

He had miscalculated. Rural Indians didn’t want to talk about hot water; they wanted to talk about cold milk.

“We were a classic case of a technology looking for a problem to solve,” Grama says.

“India is the largest producer and consumer of milk in the world,” he explains. “And all that has to be collected in this very time critical process, which leads to a lot of spoilage, [or] low quality milk that’s been sitting around for hours in the sun before it gets to a refrigeration facility or processing facility.”

So Grama, who grew up in Romania and moved to the United States when he was 18, set aside his award-winning solar water heater and focused on milk instead.

He moved to India and soon realized the main thing making milk go bad was unreliable power.

“The thing to understand is that all these villages do have power, [but] they don’t have it 24 hours a day.”

In India, most milk is collected in small amounts by rural farmers scattered across the country.

Credit:

Promethean Power Systems

But the MIT alum figured that if he could tap into the power grid when it was on and store energy, he could keep milk cold. The challenge was building a better battery.

His solution came in the form of a thermal battery, which slowly releases stored power.

“It’s like making ice. We make ‘ice.’ The process of freezing material stores energy and when that material melts it releases the energy.”

It worked. And Grama’s company, Promethean Power Systems, has now sold about 300 large industrial milk chillers in India. This means millions upon millions of gallons of milk are no longer being wasted. Meanwhile fewer people are getting sick, and small rural farmers aren’t losing so much money.

The MIT Sloan School of Management was so impressed with Grama — his business successes, and failures — that they’re bringing him in to teach a fall seminar. He’ll be the school’s first-ever entrepreneur in residence focused solely on the developing world.

“Many entrepreneurs fail the first, second, even third time, and having someone who can be honest with the students is very important,” says Georgina Campbell Flatter, the executive director of the Legatum Center for Development & Entrepreneurship at MIT.

The center emphasizes that inventions are only useful if they’re used. They encourage students to get out of the lab and into the developing world to tackle real problems.

Flatter offers a couple examples: “How do I think through the import/export challenges of moving my medical device from Boston to Lagos? How do I share profits with an artist who lives in rural India when they don’t have a bank account?”

Recent MIT master’s grad Cyril Masud Khamsi is one of the young entrepreneurs grappling with such problems. He’s now camped out at a shared workspace on campus, at the Martin Trust Center for MIT Entrepreneurship, launching a company to improve trucking services in Rwanda.

“I used to work in Rwanda, and I was working with farmers, and we had major struggles securing transport that was reliable for them and also that wasn’t taking a large portion of their margins,” says Khamsi.

He describes his company as Uber for commercial trucks in Africa. He’s been getting guidance on an almost daily basis from Grama.

Khamsi says, “This program is trying help push us to make sure we’re not just coming out and often looking at things very simplistically or paternally: ‘Oh these people have some problem, poor them. I know, I have the right knowledge, let me go fix it for them.’ I don’t think that works well.”

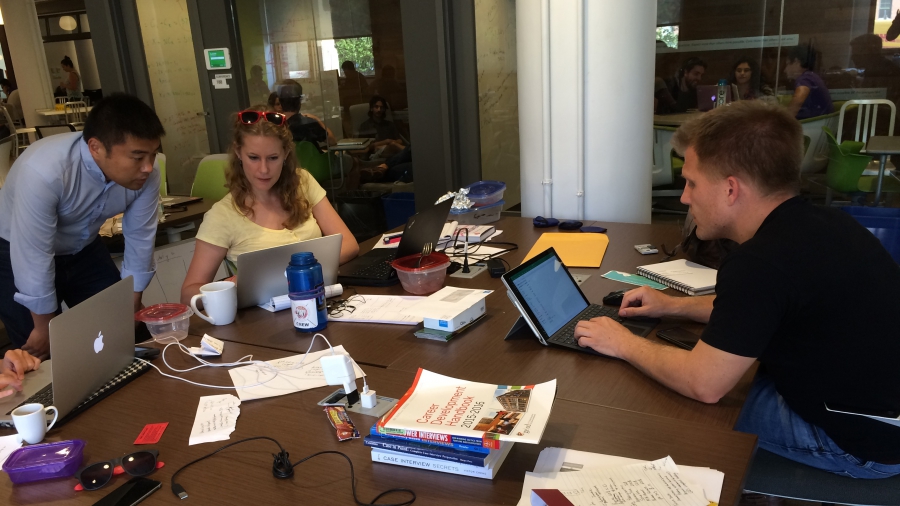

Students work at the shared workspace, the Martin Trust Center for MIT Entrepreneurship. Cyril Masud Khamsi is on the right.

Credit:

Jason Margolis

Of course there’s also the Steve Jobs philosophy. The Apple co-founder famously said, “A lot of times, people don’t know what they want until you show it to them.”

“It’s a good point,” says Grama. “But I think very few of us are like Steve Jobs.”

Sure, inventors can get lucky, Grama says. But he knows first-hand that it’s best to understand the market before you design a product.

Millions of Indians enjoying more fresh milk are no doubt glad Grama has come to see things that way.