Mary Twachekwa, 52, had no idea she needed a birth certificate to get a passport.

“I have been asked to attend a church conference in America. I went to apply for a passport and they asked for my birth certificate. It was the first time I knew about the need for one.”

Twachekwa is waiting in a queue that snakes past rows of plastic chairs and spills out into the corridor at Monrovia’s bureau of statistics in the hope of getting her birth registered.

Josephine Johnson, 21, is in the same queue. She is going to university elsewhere in Africa and needs a birth certificate to enrol. She says her mother didn’t know she needed to register her birth when she was born.

Michael William, 25, is here to get a replacement birth certificate because he is trying to join his fiancee in the US. He recalls that he did have one before Liberia’s civil war, but says his parents’ home was destroyed and all the family documents with it.

“People have no idea of the implications of not having [a birth certificate]; that is until they need one. It has so much impact on travel, study, medical care,” says Liberia’s assistant minister for statistics, Chea Sanford Wesseh.

“It doesn’t matter most of the time but, for example during elections, it can be a big problem. We can’t even prove a voter is old enough to vote. And how can you prevent things like child marriage if you can’t prove how old someone is? Or if your child is abducted, how do you prove it is yours?”

Wesseh says no one knows how many Liberians have a birth certificate due to a lack of census data, but says it is “extremely few”, despite laws stating that births and deaths must be registered within 14 days.

In 2007, the UN children’s agency, Unicef, estimated that Liberia had the second lowest rate of registration in the world at 4%.

“Death registration rates are also a problem, less than 5% are registered. Ebola death rates may have been higher because there are an estimated 10,000 people [for whom] we don’t know how they died.”

Logistics have been the main barrier to registration. Until recently the only place to register was the bureau in Monrovia, something many of the country’s citizens can’t afford to do. Almost 70% of Liberians live below the poverty line, according to the World Bank.

Before the civil wars, some births were registered in hospitals, but as Esther Thomas, Liberia’s birth registration coordinator, explains: “It was a paper-based system. Officials would give a hand-written certificate but not keep a record of it so there was no way to verify numbers or track the system. And of course so much was destroyed during the war anyway so whatever few records were there are gone.”

But things are slowly starting to improve. A joint programme by the government and Unicef has trained vaccinators in health clinics to register births, and community volunteers are also being instructed in how to do so in outreach programmes in rural villages. One-stop registration centres are being set up across the country so that people only need to travel to their nearest town rather than the capital. These efforts have resulted in 25% of under-fives getting registered by 2013. In that same year, 79,000 children were registered at birth.

The Ebola outbreak, though, dented progress. In 2014, when many health facilities were closed, registrations dropped to 48,000 – a 39% decrease on the previous year. An estimated 70,000 children born during the crisis remain unregistered.

“Registration is a prosaic issue but it is fundamental,” says Sheldon Yett, Unicef representative in Liberia. “It is also a huge child protection issue because we know children can be trafficked, illegally adopted or disappear without a trace. Without a document there is no proof that child even exists.

“And without death registration, how can we properly monitor the long-term impact of health programmes if we don’t know what people are dying from?”

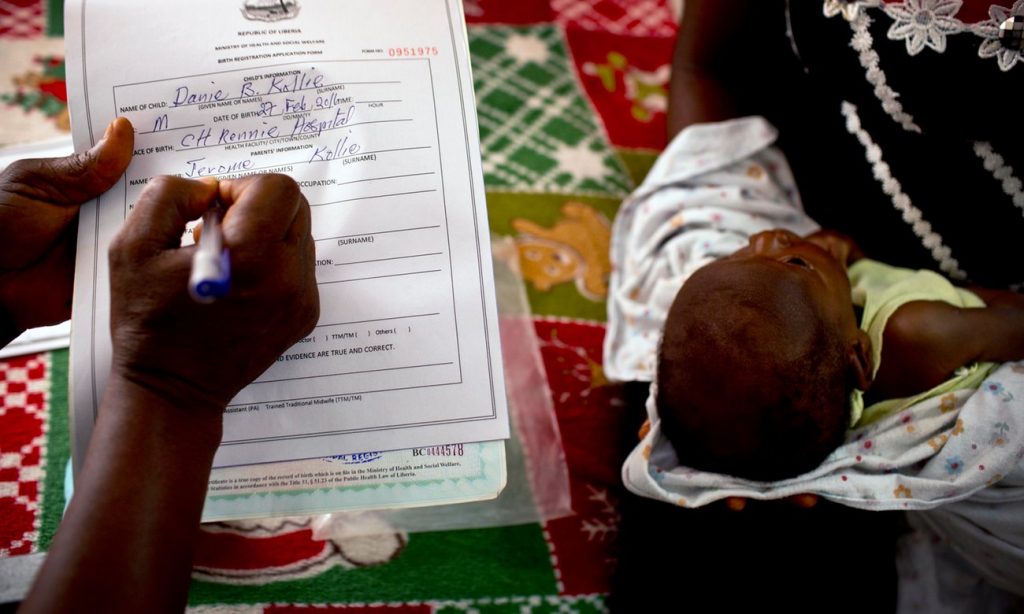

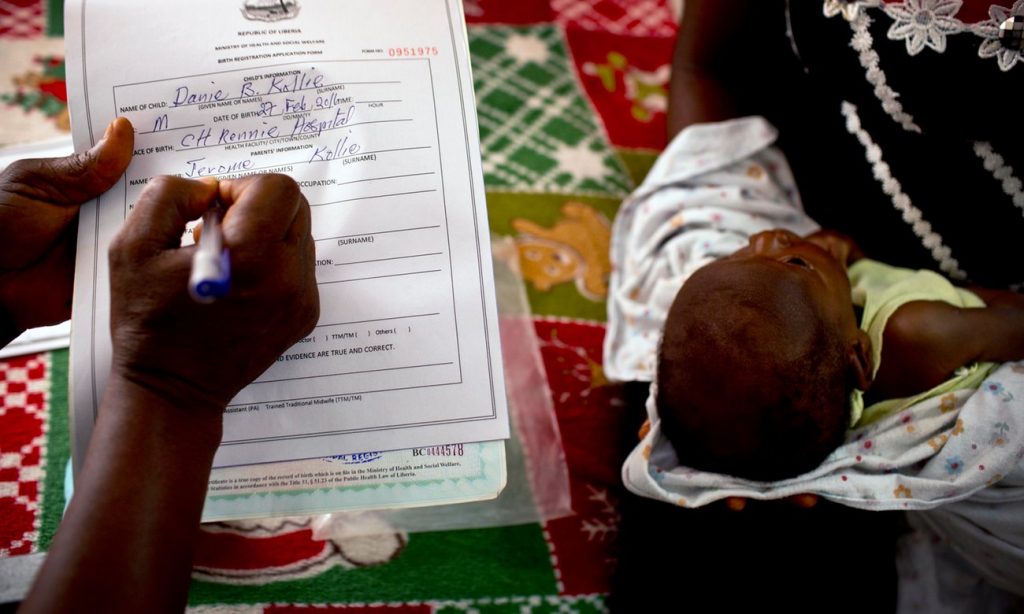

At Kakata Rennie hospital in rural Margibi county, south of Monrovia, principal registrar Edwin Yarkopwalo and his team make daily visits to the wards seeking out children to register. Once they are registered, certificates are printed in his office.

“Normally people don’t even know what a birth certificate is, let alone why they need one. By going directly to [the parents] I am able to explain the importance of it.”

Mercy is at the hospital with her six-month-old daughter, Flomo. “I was surprised when this man told me about this thing, that to be a citizen my child needs this. It is good to know this and I will keep it safe for her.”

The government has set a target of 80% of newborns registered by 2018. However, Wesseh points out that although the issue is “one of the most important aspects of anyone’s life” it is not attracting much funding.

“We need to scale up the decentralisation and make it easier for people to register locally but we can’t do that without funds,” he says. “We can’t fine someone for failing to register a child or disposing of a body without documentation if we don’t give them a way to get the documents they need.”