Mangar Makur Chuot left Sudan as a child after his father was killed during the civil war. He lived for eight years in a refugee camp in Kenya before his family were granted asylum in Australia. To launch the Guardian’s Dear Australia series, we tell the remarkable story of South Sudan’s 200 metres hopeful and how he’s heading to the Olympic Games and a possible match-up with Usain Bolt.

On the blocks for the start of the 200 metres at the Rio Olympics, Mangar Makur Chuot will carry on his back the name of the newest nation on Earth and, on his chest, the name of one of the men who helped liberate it.

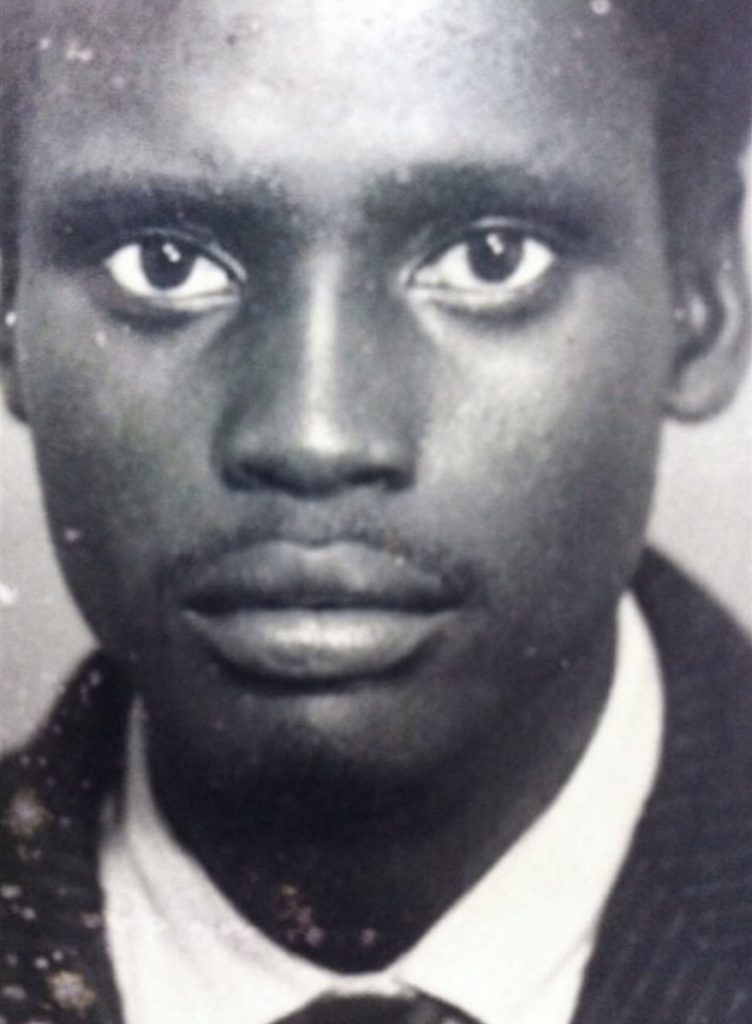

Chuot’s father, Makur Chuot, was a chief and a judge in his village, in what was then Sudan, a country stricken by near-constant drought and riven by a brutal, intractable civil war. When Chout was four a raid on his village by a rival faction saw his father murdered in a hail of bullets.

“Our village got attacked and he had to fight and he was killed,” Chuot says. “He had to fight to save his people, and he died doing that.”

Two decades on, Chuot is now a dual citizen of South Sudan – the country his father died for but whose emancipation he never saw – and Australia, the adopted country he arrived in as a refugee.

Chuot belongs, he says, to both places.

“Australia will always be part of whatever I will do in life,” he says. “Because all I have achieved now, without Australia, I could not have done it.”

His story is the first in Dear Australia, a series of films by the Guardian charting the lives of refugees in Australia – telling their stories, recognising their contributions, understanding better the trials and tribulations that attend being forced from home.

South Sudan

In Rio, Chout will run for the land of his birth and for his father, whose name he will carry on his chest on to the track.

Makur Chuot, he says, “died a hero”.

“It is for the honour of him. In our tradition in South Sudan, this is how it works. I’m Mangar, and my surname is my father’s and my grandfather’s names, Makur Chuot. He was Makur … it’s our role as boys to carry our ancestry, to carry the name.”

South Sudan emerged from more than four decades of Sudanese civil war – at the cost of hundreds of thousands of lives – to be declared the world’s newest nation on 9 July 2011.

But independence has brought neither peace nor prosperity to the South Sudanese. The country remains benighted by famine and drought, and the early promise of freedom has faded, replaced by a desperate descent back into internecine violence.

The country has almost no sporting facilities and few people who might use them. Generations of children were forcibly conscripted into armies instead of being taught to play games.

But the children of South Sudan can go to the Olympics now. “And we are going to arm them with sports instead of with guns,” Wilson Deng Kuoirot, South Sudan’s Olympic committee president, promised when his country was admitted to Games ranks.

The country will send its first team to the Rio Games, a bare handful of athletes. They don’t yet have uniforms or plane tickets. But they will be there, Chuot among them.

Like his country’s tortuous route to liberation, Mangar Makur Chuot’s path to the Olympics has been a triumph of will over difficulty and disappointment. After violence forced him to flee his country, and years in a distant, crowded refugee camp, he was given a new home in Perth, Australia.

His first attempt to make a Games team was marred by a freak injury but he came back to win an Australian national championship two years later.

Now, on the verge of becoming an Olympian, Chuot is still forging his own path.

The singlet he trains in, printed with the name of his country and its flag, he had to make himself, because no official gear exists. His coach and supporters have scrimped enough money to buy him a new pair of spikes, bright blue and monikered with the name of a man he may race against in Rio: Usain Bolt.

Kakuma

In the aftermath of his father’s death, Chuot lived with elderly relatives, the traditional life of a boy of the Dinka tribe. His job was to tend to the family’s herd of cattle on the savannah surrounding the village, a place where lions were an occasional, but very real, danger.

“You wake up as a young boy, four, five, six years old, and your job is to look after young cows. Take them out there in bush … come back home. Thinking about it now, dangers are there, wild animals eating some cows. Some big boys, they were allowed to have weapons to shoot off lions going to attack us.

“It was normal back then, but when you think about it, it’s what made me very tough, really adaptable … even though things are hard I know I’ve done a lot when I was young, I’ve suffered along the way. It builds you as a person.”

Chuot’s mother, meanwhile, fled the war that killed her husband, seeking a safer land for her six children. She fled first to Ethiopia then walked south hundreds of kilometres, crossing the border into Kenya, where she found the massive, sprawling Kakuma refugee camp, a sanctuary for those fleeing conflict and drought on the African conflict for a quarter of a century.

“After my father died, my mother had to make a decision,” Chuot says. “The decision was our future. Looking back now, she tells stories of what she went through, all these people she saw dead on the way. A lot of women, they made that decision, to sacrifice themselves … for our future.”

Chuot’s mother, Helena, established herself in Kakuma camp, running a small business selling food and drink to raise, little by little, enough money to book her children spots on a cargo plane that would deliver them from their homeland.

Chuot arrived in Kakuma as an eight-year-old to find a place scarcely better than the one he had left.

But Kakuma offered one thing the instability of conflict-ravaged Sudan could not: an education. School was in a sweltering tent from 9am to noon every day. Chuot went every day.

“It was very tough life, when you think about it. You’ve got to wait for ration from UNHCR once a month, and it’s one tin of food for one person. If you cook it in one day it finished in one day. So it’s very tough. At same time, it was better than the situation back home, you could go to school and learn English. That was the good thing of it.”

After eight years in Kakuma refugee camp, a place where thousands have spent decades displaced, Chout’s mother and her seven children were among the fortunate few selected for resettlement via the UNHCR’s global program in 2005. They came to Australia.

Photograph: Ben Doherty for the Guardian

Australia

The 16-year-old Chuot found the adjustment at once easy and difficult. The Australia he found was “a blessed place” but all of the houses in his new neighbourhood looked the same, and he needed friends to tell him how to catch a bus.

But he soon discovered – or was discovered – running, by the sprint coach Lindsay Bunn.

Bunn is the Cerutty-esque doyen of sprinting in Western Australia, a man with a famed ability for unearthing potential in out-of-the-way places and moulding it into an athlete.

His squad trains this evening in fading light on a grass track next to the stadium where Chuot has completed his final run-throughs. It is a cosmopolitan group, with runners from Afghanistan, the Seychelles, Liberia and remote communities of outback Australia.

Bunn once described seeing Chuot run in a park for the first time as like watching “a giraffe on amphetamines”. It is a line he now regrets for the regularity with which it is repeated back to him.

“But I didn’t think he was that quick. He made a lot of noise, and there were a lot of arms and legs going round … but he really had no idea. He was certainly not the quickest that came to the park.”

But Chuot was willing. To listen and to learn. Bunn taught him how to run – “you don’t throw someone in a pool and expect them to know how to swim, it’s the same with running” – and from within the whirr of limbs emerged a sprinter.

“That’s what has made him an athlete: his real dedication to learning the techniques and working, working really hard at them. One day it just happened, all of a sudden it came together.”

Chuot was “no better than an eleven-and-a-half-second 100m runner” when he turned up, Bunn reckons, but with several months of unstinting effort “the speed just jumped out of him”.

Raw talent is but a fraction of Chuot’s success, Bunn says.

In 2012, Chuot, by then a dual citizen of Australia and South Sudan, had his sights set on qualifying for the London Olympics.

But the old enmities of his homeland, however distant and dormant, remained, and in the months before qualifying, Chuot was attacked three times by a group of Sudanese men, including once when they broke into his Perth house and bashed him with a length of wood, targeting his legs.

He moved in with his coach for safety.

Two months later, in his first race without pain-killing injections after the attacks, Chuot crashed to the track after a blistering start. Doctors confirmed a hamstring tear, right on the spot where he was attacked. An Olympic dream vanished in an instant.

Four years on, the gregarious Chuot remains uncharacteristically reticent to talk about the attacks. “We finish that a long time ago,” he says. “We never want it to come next to us.”

But Bunn says, for all of the turmoil and trauma of the time, the adversity was the making of Chuot as an Olympic-level runner.

“That’s why Mangar is a great example: he knuckles down and does the work,” Bunn says. “He gets disappointments and setbacks, but he gets over them quickly and resets himself and goes harder again. It’s those qualities that makes great sportspeople. It’s the thing he’s got: resilience.”

Bunn and Chuot share something deeper than an athlete-coach relationship. Bunn babysits Chuot’s four-year-old daughter as he juggles training with university studies. The coach occasionally cooks meals for his runner and, together, the pair plot their training programs and the races they’ll run.

They have precious little funding for it. Two years ago they spent a national championships in Melbourne sleeping on the floor of a friend’s housing commission flat and catching a tram to the track.

Photograph: Ben Doherty for the Guardian

Chuot won the national title for the 200 metres in a time of 21.08 seconds.

Bunn says he regularly “pinches himself” at how far his charge has come.

“When you get the background story of the fact he never went to school until he was 12, or saw a television until he was 11, and some of the things he had to go through in the refugee camps, they were really difficult times, you do wonder at the person he’s turned out to be, how incredible it is for him to have survived all that and turned out to be such a positive person.”

Chuot says despite the hardship of his early existence, he feels he has much to be thankful for. He says he will be forever grateful to Australia for, in his words “giving a chance to somebody like me, a young kid that is out there”.

Beside’s Chuot’s Olympic ambitions, Bunn and his athlete share another athletic passion: teaching Indigenous children in remote parts of Western Australia how to run.

Several times a year, the pair cram into Bunn’s car and drive for days visiting schools in remote parts of the state that have no track, and have never held a school carnival. There, with a set of old starting blocks and a stopwatch, they teach the children how to run, and leave their teachers with a series of drills to continue the training.

Every visit ends with a race against Chuot.

“And they are very quick, very quick,” Chuot says. “I have to get really warmed up to race these kids, because I am afraid one of them will flog me.”

But the visits are as much aspirational as they are athletic. Chuot says he feels a connection with the Indigenous children of remote communities: “They’re very tough kids, and that was me when I was young.

“I tell them about my situation and my history, and that I didn’t have people around with to show me the way. And if I can motivate anybody, our plan is always to just go there and tell them, ‘Look, you don’t have to be a sprinter, but you can be anything you want in life.’”

It’s this, Bunn says, the personal development in Chuot, in all his athletes, that he takes most joy from.

“It’s not about winning medals, it’s about … what sort of person you become.”

Chuot’s story is the perfect starting point for the Guardian’s Dear A

ustralia series, because at its heart it tells stories that go beyond the official record, and the rhetoric around refugees that make for an often unedifying debate in politics and the media. Unashamedly, Dear Australia seeks to ask our community to look past a “mode of arrival” or a visa category, to see the person beyond. Because being a refugee is never the whole story, it is only ever a part of a person, an element of their character, a piece of their history.

Across the country as the Guardian met with people for Dear Australia, a recurrent theme resonated powerfully in every interview: that of refusing to be defined by the singular fact of being a refugee. People are sprinters and doctors and students and poets, journalists and gardeners and restaurateurs. They are mothers and fathers and daughters and sons. They are husbands and wives and friends.

They lead lives of extraordinary achievement, of burning ambition, of quiet industry. Lives too, of difficulties and setbacks, of frustrations and failures. Lives like any other. Too commonly, when the world talks of forced migration, those at the centre of the debate are voiceless in the discussion. Refugees are instead defined by the stories and the words that others use about them. This series is a chance to put their stories first.

Photograph: Ben Doherty for the Guardian

Rio

For Chuot, the most extraordinary chapter of his story remains unwritten. Ahead now lies Rio, the realisation of a long-nurtured dream.

Since his early meetings with his coach, a place at the Games has been Chuot’s singular ambition.

“Mangar was very clear that he wanted to go the Olympics,” says Bunn, who has taken an honorary role as a coach for the South Sudanese athletics team. “And I told him I’d give it my best shot and help him as much as I could. In a sense, I am honouring that commitment.”

There is the very real chance that, come 16 August, Mangar will find himself drawn to race the fastest man ever to walk the Earth, the man whose name is on his new running shoes: Usain Bolt.

Chuot says he is undaunted. “It’s a privilege to run against Bolt, I’ll try the best I can, give it my best shot. You never know what will happen.”

But Chuot sees his competing at the Olympics as being a part of something far larger than a result, or a time, or a medal. His race is his small role in the evolution of his homeland, the world’s youngest independent nation, teetering again on the verge of collapse.

“For me to be part of the people who put up the flag of South Sudan is something very special, because we had people who gave their lives to make this a nation. It is in honour of my father and all of the other brothers and sisters and mothers, the uncles and fathers of other children that couldn’t see this moment,” he says.

The Games, he hopes, will be cause for celebration in a country that has had little to exalt, and a small step towards a peace it has barely known.

“The peace will come from us, the youth who really suffered, who knew and experienced the hardship our parents went through. I think the bright future of South Sudan is within us.”