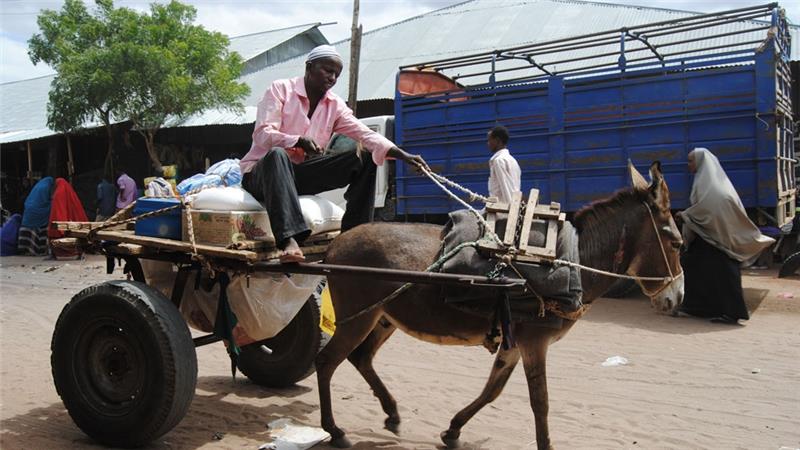

![A man ferries goods from the market in Hagadera camp in Dadaab [Anthony Langat/Al Jazeera]](http://abovewhispers.com/wp-content/uploads/2016/07/Somali-Camp.jpg)

When war broke out in Somalia, Deck’s parents were among the first to arrive at Dadaab in 1991. “My parents have told me that I was just one year old when we came. But they haven’t even told me the name of the village we came from in Somalia,” Deck says.

At the camp, his family lived in poverty and depended on food rations to survive. His mother struggled to make their lives better by selling firewood. She later opened a small clothes shop at the camp’s market. Life got better and Deck and his siblings attended school. For Deck, the camp has always been his home, a peaceful place from which he has never ventured.

Upon finishing primary school in 2008, he started working in the family business. He now spends his days at his family’s shop, selling men’s shirts, trousers and shoes.

The shop his mother started through the proceeds from selling firewood has grown and can now comfortably provide for their family. It now has stock worth approximately $850, he estimates.

But Deck’s life may soon change if Kenya makes good on its plan to repatriate the Somali refugees from Dadaab. Joseph Nkaisserry, Kenya’s cabinet secretary for interior, first made the announcement in May. He said the camp was a threat to security and had been used to plan attacks within the country. The government expects to close it by November.

Mwenda Njoka, the Ministry of Interior spokesman, told Al Jazeera that the first group of 15,000 refugees would be taken to various places in Somalia on July 1. “We are currently conducting a workshop for all officials from different agencies which will be involved in the repatriation. We are also working closely with the UNHCR in planning the repatriation,” said Mwenda.

![Deck Yusuf Mohamed, left, attends to customers at his family's shop in Ifo refugee camp [Anthony Langat/Al Jazeera]](http://abovewhispers.com/wp-content/uploads/2016/07/Somali-in-Kenya.jpg)

‘I am happy here’

Dadaab refugee camp has 326,611 Somali refugees (75,169 households) in its five camps – Ifo, Ifo 2, Hagadera, Dagahaley and Kambioos. Ifo camp, where Deck lives is home to 76,121 refugees. Ifo is the oldest camp in Dadaab and was opened in 1991, when civil war broke out in Somalia.

Deck has never returned to Somalia – he hasn’t even left the camp – and he is reluctant to now. “I am happy here, security is good and business is good too. But repatriation is going to end all this and force us to a place where there is war,” he says.

Hussein Abdullahi, 27, is a tailor at Ifo. He is deaf, as are three of his friends, two of whom are teachers and one a barber. They worry that because they are unable to hear, repatriation will be even more dangerous for them. “If a bomb or gunshots occur, we are unaware and may end up losing our lives,” Hussein reflects.

He arrived in the camp in 1992, when he was three years old and has never left. He was educated at the camp and can read and write well, something he says may not have been possible in Somalia due to war and the poor educational system. He now plies his trade at Ifo market, where he sews trousers and shirts for other residents of the camp.

Because of the uncertainty about the future of the camp, he opted not to pay his shop’s rent this month, working instead from the verandah of a closed shop. This way, he says, he’ll be able to save a little money in case he’s repatriated soon.

“If we could hear, if we were not deaf, we could have gone back without hesitation,” Hussein says. “At least then we could run away if tragedies occur.”

One of his friends, Hussein Aden Ali, 27, is a barber, but he is now out of work since his employer shut his barber shop after hearing about the repatriations. “Many people are closing their shops and selling their goods out in the open – some at throw-away prices – in anticipation for the repatriation,” Deck says.

![Deck Yusuf Mohamed's family shop was set up by his mother, with the proceeds from selling firewood [Anthony Langat/Al Jazeera]](http://abovewhispers.com/wp-content/uploads/2016/07/Somali-Deck.jpg)

‘I would rather earn less here and be safe’

At Hagadera camp, about 5km from Ifo camp, some have voluntarily left for Somalia, but 22-year-old Mohamed Ousman says he is not yet ready. His family left Buale in Middle Juba 21 years ago. Some of his former neighbours in the camp returned there last December.

“When we speak on the phone they tell me that right now there is peace but al-Shabaab fighters are in the region. So if we are forced to go, we never know when the operation will be at Buale and that will put us at risk. I don’t want that,” Mohamed says.

Mohamed finished secondary school at Hagadera in 2013 and when he was unable to get a scholarship to study medicine – his dream career – he settled for teaching. In 2015, he started teaching maths and English to class five and six pupils at a Lutheran World Foundation-funded school at Hagadera. He says he would love to go back to a peaceful Somalia some day and be assured of a job.

At the school where Mohamed teaches, some of the children have already left for Somalia. He fears they may not have access to an education there.

According to SAFE, the Somali and American Fund for Education, decades of civil war have led to a collapse of the education system in Somalia. It says that 90 percent of all schools were destroyed during or after war. SAFE estimates that 80 percent of school-age children are not enrolled in school.

The Un refugee agency, UNHCR, has been repatriating refugees from Dadaab who want to go back to Somalia. So far, it has repatriated 16,000 over the course of three years. David Mwancha, a UNHCR spokesman, said that once in Somalia, the refugees are provided with food and the agency also ensures that the children get enrolled into school.

Mohamed says that some of his friends who have returned to Somalia tell him that there are government jobs that pay better than at the camp. Since 2012, the Somali government has embarked on an education sector strategic plan with funding from the Global Partnership for Education. But Mohamed isn’t convinced.

“That is tempting, but I would rather earn less here and be safe in a peaceful place than earn more and risk my life,” he says.

![A young boy leaves the market place at Hagadera camp in Dadaab [Anthony Langat/Al Jazeera]](http://abovewhispers.com/wp-content/uploads/2016/07/Somali-Boy.jpg)