Photograph: Ryan Brown

When Ebola struck Sierra Leone in 2014, its terror lay in its mystery. It was a gruesome disease that no one had seen before, and claimed lives without apparent cause or cure. But Mohamed Moray had a broader perspective.

“It was just like the war,” he says, referring to the civil conflict of the 1990s, in which an estimated 50,000 people were killed or had limbs hacked off by rebel fighters.

Now, as then, communities were splintering under the twin pressures of fear and suspicion; amid the chaos, few had the chance to mourn properly for those whom they had lost.

Moray knew exactly what that dangerous alchemy of fear and grief could spawn – anxiety, depression, post-traumatic stress disorder – because he had watched it happen before.

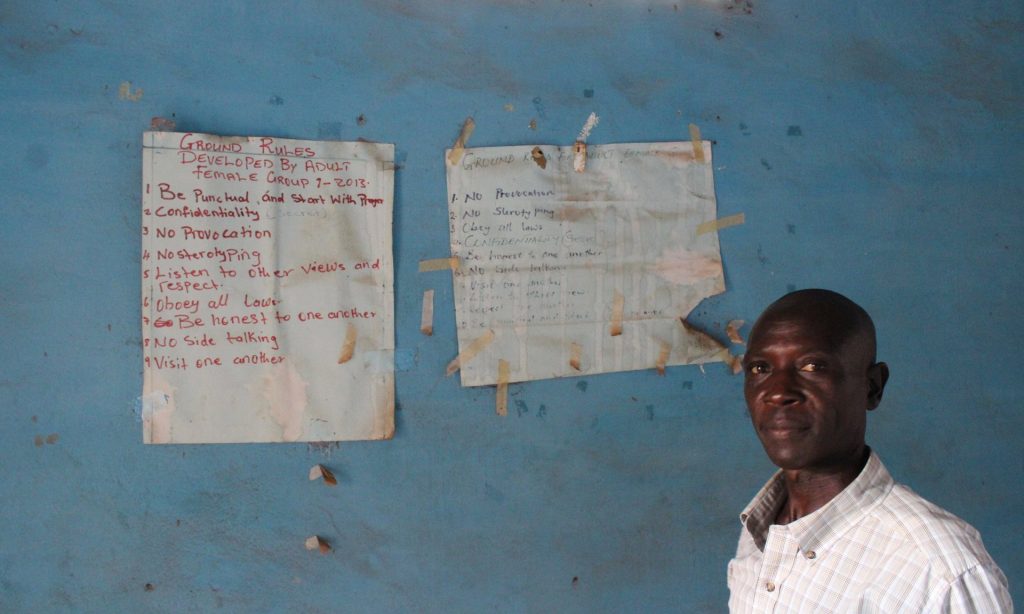

“A man who knows how to swim cannot watch his friend drown without feeling great stress,” says Moray, clinical supervisor for the regional branch of the Community Association for Psychosocial Services (Caps), which has provided counselling to communities around Kailahun in eastern Sierra Leone since the end of the war. “So when we saw this happen again, we felt a responsibility to do something.”

For nearly two years, Ebola stormed across this corner of west Africa, devastating communities and health systems that were already among the world’s poorest. But within that public health emergency was a second crisis, acute but nearly invisible: one of mental healthcare.

When Ebola hit, just 136 doctors were working in the public sector in Sierra Leone, a huge shortfall for a population of roughly 7 million people. But there was also just one active psychiatrist, a wry 70-year-old who spent his mornings scribbling prescriptions at the country’s only psychiatric hospital in the Kissy neighbourhood of eastern Freetown.

At this institution, which is also the oldest on the continent, most patients are kept chained. Treatment consists of little more than a daily dose of expired antipsychotic medication.

To Moray and his team, this state of affairs was frustrating, though hardly inexplicable: in the years during and just after the civil war, they had watched as money and expertise poured into the country in an effort to help mend emotional wounds.

A series of initiatives promised community healing, psychosocial support and empowerment. The confessional bonfires of one such project – which brought perpetrators and victims together in public pleas for forgiveness – even featured in the acclaimed documentary film Fambul Tok.

Photograph: Ryan Brown

Moray and his fellow counsellors had started out as clients – and later employees – of the Center for Victims of Torture (CVT), an international NGO that provided counselling to Sierra Leonean refugees in Guinea in the 1990s and early 2000s. For several years, they criss-crossed Guinea, and later Sierra Leone, providing trauma counselling to those who needed help, as they once had.

“The passion I have to help people with this has always been because I have gone through a similar experience,” says Edward Bockarie, whose parents were murdered during the war and who is now the executive director of Caps. “I know how I was then, and how I was after I was helped [by counselling].”

When CVT’s operation wound down in 2005, Bockarie, Moray, and the other counsellors decided to form their own group. However, international funding was waning along with interest. “People don’t wear mental health on their faces, so it can be hard to keep up the excitement in it, especially once a place returns to normalcy,” says Nancy Peddle, an American psychologist and academic who has worked in Sierra Leone for more than two decades. “People come and go, and the urgency comes and goes too.”

There were incremental changes, says Peddle, but much of the work done by international groups after the war was not formally institutionalised, with changes never integrated into the public health system.

A decade later, when Ebola struck, few formal resources were available to meet the emotional needs of – among others – the ill, survivors, bereaved family members, healthcare workers and orphans. Major health charities scrambled to train people in “psychological first aid”, but few focused on it.

After all, people were dying by the dozens as they waited for ambulances or in crowded hospital wards. Mental health, many reasoned, would have to wait.

For Bockarie, Moray and their staff, waiting wasn’t an option: they were professional counsellors, living in the eastern provinces where both war and disease had done great damage. Those who fell ill, those who were grieving or without hope – these were not faceless strangers but neighbours, friends and relatives.

In mid-2014, Moray’s counsellors began to make ad hoc house calls across Kailahun town. They would comfort a grieving widow here, an orphaned child there. “They came to my house and grieved with me, and they told me I must come to their office any time I wanted,” says Janet Sanfa, who lost her mother, brother and sister to Ebola. For more than two months, she would drop into the office two or three times a week to see the counsellors. “If not for that, I think I might have died myself,” she says.

Photograph: Tanya Bindra/AP

Soon, other organisations began to take notice of Caps’ rare expertise. By the end of 2014, its counsellors were hired out to help orphans looked after by Save the Children, burial workers employed by Concern Worldwide and Catholic Relief Services, and patients in Médecins Sans Frontières treatment centres. “It was very similar to what we saw after the war,” Moray says. “Stress, anger, depression, guilt.”

As the epidemic began to wane in late 2015, Caps encountered another familiar pattern: there were fewer international headlines, and less money.

“At the end of the day, when the funding came for post-Ebola projects, we were left out,” Bockarie says. By early 2016, the organisation’s grants had dried up.

Despite this, on a Monday morning in May, every one of Moray’s seven counsellors was at work in Kailahun, hunched over laptops as they finalised funding proposals. Outside, a Ford Ranger sat slumped on four flat tires – it broke down a year ago, say staff, and they haven’t had the money to fix it.

When asked how he earns an income now, Moray says he has a vegetable garden and rarely needs to buy food. “This is our own programme,” he says. “If we leave it, who will do it? No one.”

- Ryan Lenora Brown was a fellow of the International Reporting Project in Sierra Leone