For the past six years, the city of Zinder in Niger has been gripped by American-inspired gang violence, a phenomenon international researchers and local journalists have struggled to understand.

The street violence is popularly referred to as the Yan palais. In the local Hausa dialect, “palais” is a word for young people who mimic the clothes, drugs, music and sexualised culture of their western counterparts.

But while some journalists have offered insight into what’s happening and why, others have been accused of exaggerating the violence and over-simplifying the causes.

A recent 4,000-word report in the US publication Foreign Policy described Zinder as devastated by “days and nights of brutality”, street fights, murder, rape and armed robbery. There are “cut bodies”, “slit throats”, “crushedbones” and machetes “dull from years of cutting into bodies”, wrote journalist Jillian Keenan earlier this year.

But for those who know Zinder, the article presents a distorted reality. I recently translated the story, titled Dead Man’s Market and the boy gangs of Niger, into Hausa, and shared it with residents in the city, including members of the palais. Many claimed they didn’t recognise what they read.

“It was true that there were fights between palais youths, and people did use machetes, and there were deaths, but her description is much exaggerated,” said Ohlala, a well known palais leader. “There were certainly less than a dozen deaths in the whole five years [from 2010 to 2015] when violence was the most intense,” he added.

Oumoul Kheir, a local resident in her 50s, asked: ““Are we animals? How do these people think of us? People do not slit other people’s throats just like that.”

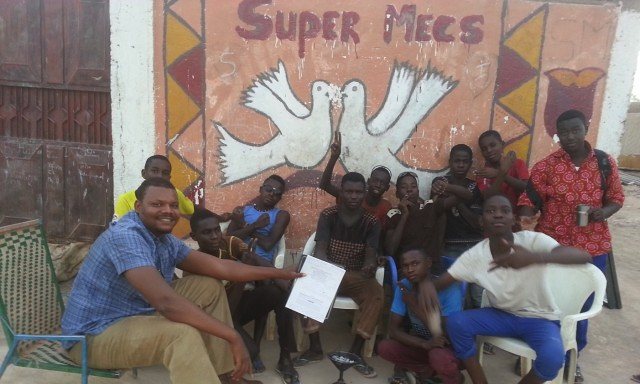

Photograph: Ibrahim Yahaya Ibrahim

DMX in Zinder

There is no doubt that there has been a rise in urban violence in Zinder over the past five years.

In 2009, the city’s police registered 258 acts of violence. This number increased in 2010 and 2011 to 551 and 952 respectively. The number of reported violence incidents peaked in 2012 at 2,016, before dropping to 1,243 in 2013.

This rise is grave, but you could argue that it’s notable only because thecity was historically peaceful.

Another mistake the article makes, as many have before, is to try and draw a conclusive link to Islamist militancy, arguing that because of local poverty, the young gangs are potential recruits for Boko Haram, which is based in neighbouring Nigeria.

In reality Zinder’s youths are inspired by American gangs. The city’s graffiti culture references DMX, Bad Boyz, Outlaw, Black Power and Gangsters City, while many of them sport baggy trousers, dreadlocks and mohawks.

According to the article’s logic, it must be puzzling that a “poor” and “dusty” city like Zinder, with a large Muslim population and located in the confluence of Boko Haram, Islamic State (Isis) and al-Qaeda, is not teaming with jihadi cells.

Perhaps the article should instead focus on the differences between Zinder and other towns in the Sahel region that do have this problem: why are some inspired by western gang culture and others look to Isis?

Veiled colonialism

Descriptions of the Yan palais phenomenon reflect a wider problem in western coverage of Africa, much of which features veiled colonial discourse imagining primitive and savage populations.

The catalogue of shocking images and stories of war, famine and disaster coming from the continent make the narratives in stories like Foreign Policy’s seem immediately understandable.

The article ends on a note of hope about the decline of the violence, but the only actor credited with playing a role is the international United Nations agency for children.The efforts of Zinder’s residents, whose lives are most affected, go largely unmentioned.

Government efforts to improve policing are omitted, as are job training programmes and the Fadas and Palais Movement for Youth Promotion, which offers young people a peaceful venue to settle disputes.

Religious leaders who organise public prayers and preach for peace are also overlooked, as are the parent associations and women’s movements who advocate for better education.

Once again, Africans appear as the victims, lacking the initiative to address their own problems, waiting desperately for others to come to their rescue.

A version of this article first appeared on African Arguments