The sky above was dark with smoke. At the railway station, as Ntsiki Makhubo and her mother returned from a day in Johannesburg, they were met by an anxious crowd.

As they stepped down from the train, they trod on shattered glass and heard the news. Your brother has been shot and killed, Makhubo was told.

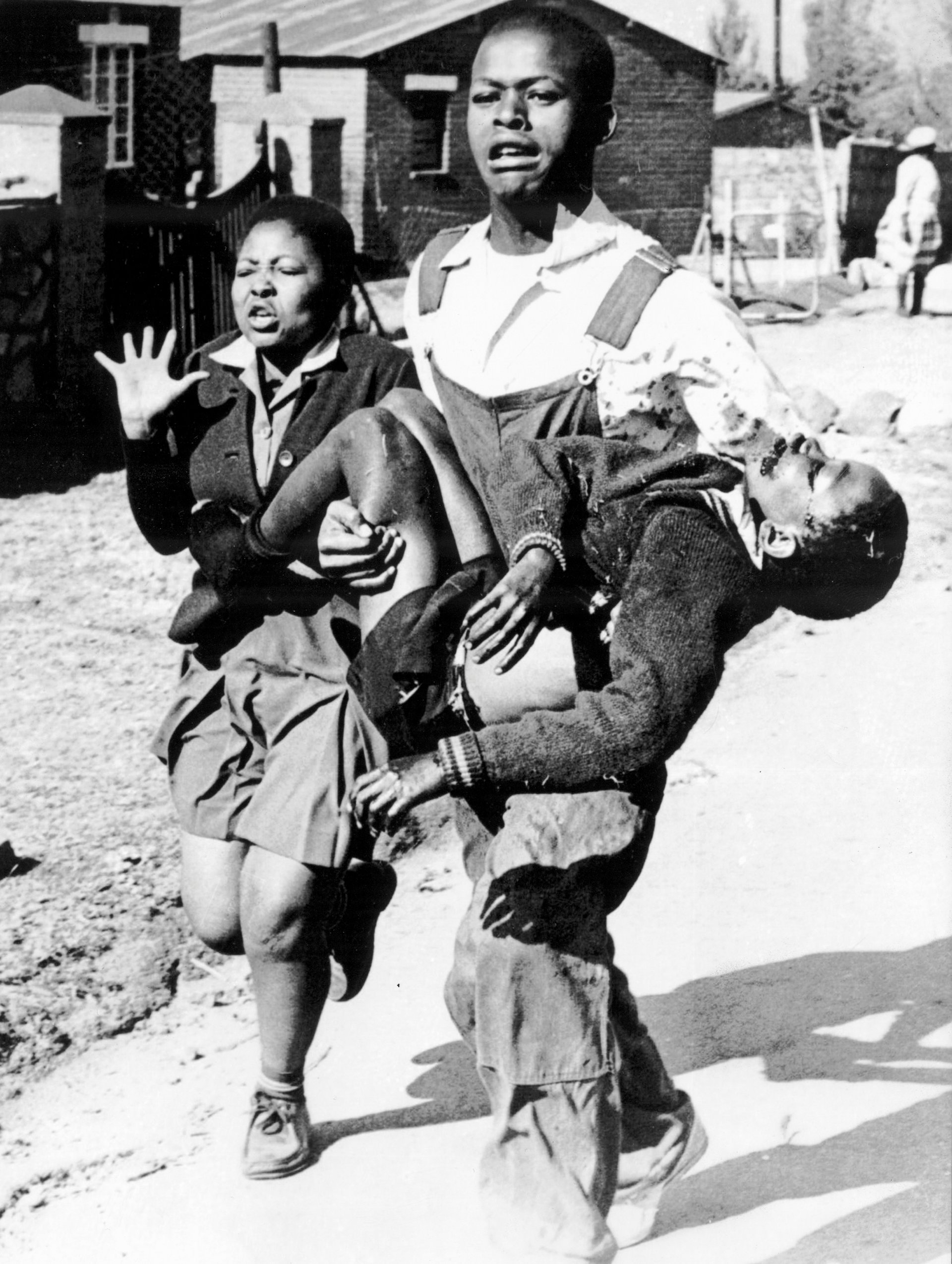

When South African police opened fire on marching schoolchildren in the township of Soweto on 16 June 1976, Makhubo’s neighbours had seen her older brother, 18-year-old Mbuyisa Makhubo, drenched in blood and staggering to a clinic, carrying a limp boy in his arms. They assumed he had been gravely hurt.

In fact, it was the 12-year-old boy Mbuyisa had scooped up in the midst of the chaos who lost his life that day. His name was Hector Pieterson. A photograph of the two taken by a local journalist was printed first by a local newspaper, and then around the world.

It would go on to have a huge impact, prompting global outrage at the police’s brutality, becoming an iconic image of the struggle against a hated racist system and prompting a new wave of protest that would eventually lead to the end of apartheid.

Today, South Africa commemorates the 40th anniversary of the Soweto uprising, as that day is now known. No one knows exactly how many people died – estimates range from 150 to 700 during the months of subsequent violence.

But the anniversary – like the famous photograph – will provoke a variety of reactions, not all of them easily reconciled.

“The uprising means different things for different people,” says Khwezi Gule, chief curator of the Hector Pieterson museum and memorial in Soweto. “There are different generations and varying constituencies. Even those who were there in 1976 were affected differently: parents, students, leaders, people just caught in the crossfire.”

Much attention has been focused on Pieterson and the screaming girl in the picture, his younger sister Antoinette. Both were pupils at local schools and were marching to protest against the introduction of compulsory tuition in Afrikaans, seen as just one more humiliation for students crammed into deliberately overcrowded, under-resourced schools designed to deny, rather than provide, education to South Africa’s black majority.

There were deeper factors too. A new generation had lost faith in its political leaders, who were mostly in jail or exile, and many were contemptuous of parents who they thought had accepted apartheid’s humiliating restrictions.

Pieterson, although not particularly politically aware, had joined his school friends to march through the dirt streets of the sprawling township to a local stadium. Police blocked their way. A standoff followed. Stones began to fly. Teargas filled the air. Then the shooting started.

“There was confusion. I saw people hiding themselves and then I hid myself too. I was afraid because I didn’t know where Hector had gone to … then I moved forward and I … saw Hector’s shoe,” Antoinette remembered 15 years later.

It was then that Mbuyisa Makhubo picked up the boy and began to run. There was little point – he was dead before he reached the nearest hospital.

But if the Pieterson family were shattered by the events that day, the Makhubo family were soon to suffer too for Umbiswa’s impulsive act of kindness.

The family had already paid a heavy price for their involvement in the anti-apartheid struggle. Key African National Congress (ANC) leaders such as Nelson Mandela and Walter Sisulu had been family friends before being jailed, and the Makhubos were well known to authorities.

Mbuyisa, his other two brothers and sister Ntsiki were frequent visitors at Mandela’s Soweto home where Winnie, his second wife, sometimes cooked for them. “She also helped me register for college,” Ntsiki said. “We used to go over and eat there: spinach and pap [maize flour mash], or sometimes grilled meat.”

Photograph: James Oatway/the Guardian

Mbuyisa’s father had joined the Umkhonto we Sizwe organisation (MK), which waged a campaign of sabotage and violence within South Africa in the early 1960s. Forced to flee to avoid prison, he lived in ANC camps in neighbouring countries before dying in 1973 in Kenya.

Within days of the Soweto uprising of 16 June, it became clear that Mbuyisa would follow his father into uncertain exile.

“I was very close to my brother. After that day, when he had carried the boy, he was disturbed, distressed. He was harassed all the time by police and journalists. Eventually he said, ‘I have to go’, and I packed him a small bag and he left for the border, to Botswana. He wrote for a while but after five years, the letters stopped. We never saw him again,” Ntsiki said.

Recently, there have been reports that Mbuyisa has been found in Canada, but no firm identification has been made and Ntsiki remains sceptical.

The family were to suffer more over the coming years as the government intensified its brutal efforts to maintain the apartheid system in the face of massive opposition, economic crisis and international opprobrium.

In 1985, it was the turn of another Makhubo son to flee: Ntsiki’s second brother. He also joined MK and left South Africa for training as a guerrilla fighter. He remained in exile until the ANC took power and Nelson Mandela became president in 1994, but died of Aids five years after returning to his homeland.

Since then, the fortunes of the Makhubo family have steadily improved – like those of their nation. Though Ntsiki herself still lives in the rundown breeze-block house on Litabe Street – from which her brother set out 40 years ago to join a march – her own children have grown up knowing relative peace.

Two of them live in Cape Town, where one is a university student and the other is a supermarket manager. The third, Zongezile, a stylish 37-year-old, still lives in Soweto, where he runs a tourism start-up.

For Zongezile, the commemoration of 1976 sends an important message. “The memory of Hector Pieterson and my uncle means sacrifice and selflessness, but it also means change,” he said.

Soweto itself is certainly transforming. There are car dealerships, new roads and bus stations, and shopping malls with major western brands. An influx of tourists to the area around the site of Hector Pieterson’s killing – now marked with a signboard – has prompted a mini-boom of souvenir shops and restaurants serving “authentic” Soweto cuisine.

The Hector Pieterson museum opened in 2002 and now has 90,000 visitors a year. Many are schoolchildren and students, who smile and pose in front of the picture of Mbuyisa carrying the dying boy.

Few of these youngsters who visit know much of the uprising, nor are they particularly interested. “I’d say out of the 40 or 50 school kids I usually take round the museum in any one group, you’ll have three or four who either know something or engage,” said Liz Block, a lecturer and volunteer tour guide.

Photograph: James Oatway for the Guardian

Ntsiki is concerned by this lack of knowledge, and fears violence might return. She was horrified when dozens of protesting mineworkers were shot dead by police near Johannesburg in 2012, and by a series of recent brutal clearances of squatter camps.

“Was the sacrifice worth it? There are a lot of positive things no doubt. A lot has been done. I am proud to be a South African. But I am still saddened. There is much that is wrong. People are still being gunned down in squatter camps when they protest. We didn’t fight for that,” she said.

In parts of Soweto too, deep poverty remains. In some areas families are crammed into apartheid-era hostel housing. In others, poor immigrants from rural areas or neighbouring countries rent tin shacks for £25 a month. The contrast with the touristy areas of Orlando West, let alone the wealthy suburbs of Johannesburg only a 40-minute drive away, is striking.

In Kliptown, on the south-eastern fringe of the township, 45,000 people live on dusty streets without access to schools or jobs. The area suffers from endemic drug abuse and violent crime. Angry community leaders talk of betrayal by their elected representatives.

“The government and politicians will come by for the celebration, do their campaign, host their events, but it has nothing to do with us,” said Bob Nameng, who runs a local community programme.

But Zongezile Makhubo insists that, despite all the problems facing South Africa and Soweto 40 years after the uprising, he is hopeful.

“Some here overlook the good we have achieved in the years of democracy and just look at the problems,” he said. “But we have shown that our country unites to face the challenges. Everyone comes together and says we must do what we can to help and that this is the country we love.”