When the Egyptian feminist Nawal El Saadawi was a young child, she wrote a letter to God challenging him to explain why women were treated differently to men.

“He never replied,” said El Saadawi, who is still as passionate about women’s rights. “I told him, ‘if you are not fair, I’m not ready to believe in you.'”

El Saadawi’s writing and political activism have made her many enemies over the intervening eight decades, upsetting governments, religious authorities and extremist groups alike.

She has received countless death threats.

Sacked from the health ministry in the 1970s, she was jailed in 1981 after criticising President Anwar Sadat and spent nearly two decades in exile during President Hosni Mubarak’s rule.

“When I was in jail, the jailer said, ‘If I find paper and pen in your cell, it’s more dangerous than if I find a gun,'” El Saadawi told the Thomson Reuters Foundation in an interview in London this week.

Described as the “Simone de Beauvoir of the Arab world”, El Saadawi has written more than 50 books, covering taboos from sexuality to prostitution to female genital mutilation (FGM).

But she dislikes any comparison to the pioneering French feminist, saying: “I’m much more radical than her.”

Unlike de Beauvoir, whom she says was dominated by her partner, the French philosopher Jean-Paul Sartre, El Saadawi proudly lives alone, having divorced all three of her husbands.

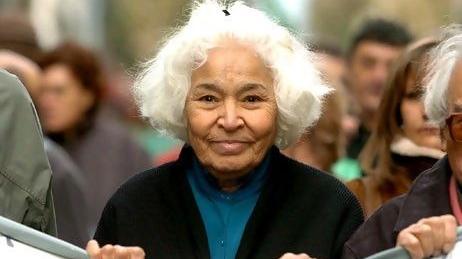

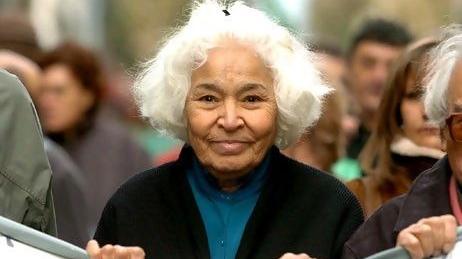

With her shock of white hair, bright eyes and ready smile, she is a force of nature who never minces words.

Now 86 and living in Cairo, she says she does not fear her opponents and enjoys huge support from young people across the Arab world. “I have lost my fear of death, I have lost my fear of prison,” she said.

CHILD MARRIAGE

In a new edition of her autobiography “A Daughter of Isis”, El Saadawi describes growing up in a patriarchal culture where girls were subjected to abuse, including child marriage and FGM.

Aged 10, she was dressed up and told to serve coffee to her first prospective husband. Unaccustomed to heels, she tripped, pouring hot liquid all over him.

An outspoken child, the young radical managed to fend off a succession of suitors before persuading her parents to let her pursue her studies, which led to medicine and psychiatry.

It was while working as a doctor in the 1950s and 1960s that she became an early campaigner against FGM.

Although El Saadawi had been cut as a young girl, she says she developed “amnesia” around the event.

It was not until she met some Sudanese women who had undergone the most extreme form of FGM – in which the vaginal opening is sealed – that she began to examine her experience.

“(The psychological effect) is terrible,” she said. “It’s the feeling you lack something, that they cut part of you. Women are deprived of (pleasure in) sex. They feel humiliated.”

Egypt outlawed FGM in 2008 but it continues.

El Saadawi says the government is too scared of Islamic groups to take robust action.

About 87 percent of women and girls aged 15 to 49 have been cut, according to U.N. data, making Egypt the country with the highest number of women in the world to have undergone FGM.

El Saadawi disputes the figures, saying educated families have abandoned the tradition.

“A lot has changed. There is marvellous progress,” she said.

El Saadawi has also courted controversy for her views on the veil – another “tool of oppression”.

She says the veil is not Islamic and is annoyed when images of veiled women are used to symbolise Arab women on her books.

STILL DREAMING

Although much of her writing examines the status of Arab women, she says patriarchal oppression is everywhere. She ranks Islam as less oppressive than either Judaism or Christianity.

“After travelling all over the world … I discovered that girls are brought up in a very similar way – we are all in the same boat. The patriarchal, religious, capitalist system is universal.”

El Saadawi does not believe anyone will hand women their rights – women need to organise themselves and fight.

“I have had a dream since I was a child. A very mad dream, but very simple – to change the world,” El Saadawi said.

“The dream is still alive.”