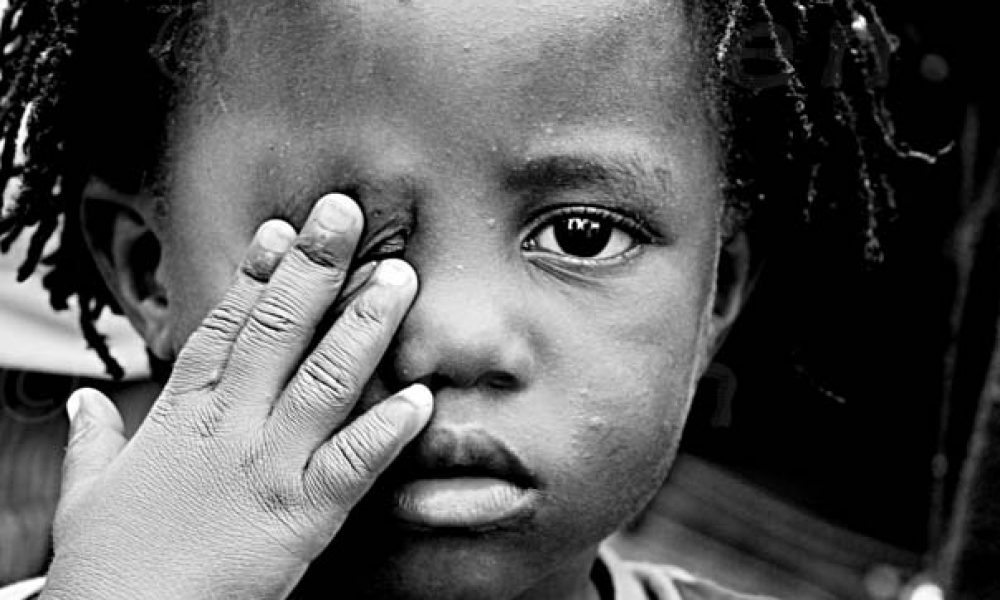

This year about 12 million of the world’s children will be married before they turn 18. UNICEF figures suggest about 18% of them will be boys and about 82% of girls.

Child marriage is widespread across developing countries, cultures and religions. It violates the rights of children and has widespread and long term consequences. It is driven by gender inequality, poverty, patriarchal traditions and the precarious socio-economic position of women, especially in rural areas.

The practise continues in the Middle East and Africa, even though many countries have laws banning it. In West Africa, Niger has the highest prevalence: 76% of all marriages there involve children. It is followed by the Central African Republic with 68%, Mali with 52% and Guinea with 51%. In North Africa, the figure for Mauritania is 37%; Egypt 17% and Morocco 13%.

The practise continues in the Middle East and Africa, even though many countries have laws banning it. In West Africa, Niger has the highest prevalence: 76% of all marriages there involve children. It is followed by the Central African Republic with 68%, Mali with 52% and Guinea with 51%. In North Africa, the figure for Mauritania is 37%; Egypt 17% and Morocco 13%.

Child marriages are slowly declining. Progress is most dramatic when it comes to the marriage of girls under 15 years of age. In North Africa, the percentage of women married before age 18 has dropped by about half, from 34% to 13%, over the past three decades. Nevertheless, child marriages are still prevalent in the region.

In my book, “Le marriage des filles mineures au Maghreb”, I explore the impact of child marriages. In particular, I show how the marriage of underage girls has a devastating effect on their lives. I also show how it hinders countries from achieving the UN sustainable development goals. This is particularly true when it comes to education, health, gender equality, and the fight against poverty.

Yet the problem is rarely integrated into the national development debate and is seldom tackled by governments. The book shows that Morocco, Tunisia and Algeria have ratified international human rights treaties and adopted universal conventions, but aren’t putting them all into practice.

There have been some encouraging signs. The three North African countries have made headway in educating girls and improving their living conditions during the past four decades. This has contributed to a decrease in child marriage.

They are good examples of effective intervention to end child marriage.

But Morocco, in particular, still has much further to go. More than 30,000 underage girls entered into arranged marriages in 2018. The country reformed its family law in 2004 but still allows young girls to marry before the legal age of 18 with the permission of a judge, and under circumstances such as pregnancy. The conditions remain vague.

It’s also a country where violence against women is not receding.

Forced despite consequences

Several economic, social, and cultural factors drive underage marriage. Poverty and old traditions often force young girls into it. Families calculate that there will be one less person to feed when a girl goes to her husband’s home.

A reason often cited is family honour. Families overlook the fact that child marriage often leads to domestic violence, divorce and sometimes even suicide.

My book argues that, regrettably, legal measures to protect women and girls by criminalising child marriage face substantial hurdles. These include a conservative culture, the accommodation of religious fanatics, and gender-based discrimination.

The consequences of child marriage can be devastating.

Little girls see their childhood curtailed and their adolescence confiscated. They run medical risks. Many girls don’t survive the first pregnancy and die during childbirth. They may suffer mental health problems, as well.

Girls are also forced to drop out of school.

Steps towards ending child marriage

Women’s and human rights organisations emphasise the need to end child marriage through legislation. They also call for severe sanctions against violations of the law and violence against women.

In my book I also stress the need to establish and implement laws and policies that criminalise child marriage. These marriages should become illegal, with no exceptions. Facilitating or participating in them should be made a criminal offence.

But the legal route is not enough. Other steps need to be considered. These include:

To meet the Sustainable Development Goal of eliminating child marriage by 2030, governments and civil society leaders in North Africa should continue their efforts to reform family laws.

Moha Ennaji ‘s most recent books are Minorities, Women and the State in North Africa and Moroccan Feminisms.

Moha Ennaji, Professor of Linguistics, Gender, and Cultural Studies, Université Sidi Mohammed Ben Abdellah