Sudan stands alone as it protests thirty years of oppression. And yet so much of its struggle resonates across Africa and the world.

Sudan struggles alone. The government’s reaction to nationwide protests has been brutal. The uprising began on 19 December and continues to pick up numbers and energy over a month later. So far, at least 40 people, but probably many more, have been killed by security forces. Hundreds have been beaten and severely injured. Thousands have been detained.

As always, these numbers mask the real human cost of state violence. On a single day in Khartoum, university student El Fatih Nimeir was shot in the head and died; Dr Babakir Abdelhamid, a doctor who had been treating protesters in his home, was apparently executed; Dr Mauwia Khalil, another doctor tending to those hurt, was killed despite reportedly approaching police with his hands up.

Each of these stories, occurring almost daily around Sudan as it rises up against 30 years of oppression, is a tragedy that demands attention. Yet the response from beyond Sudan has been muted.

The international media has been quiet, while government reactions have been tepid. This has led some to point to Western powers’ own interests in keeping Omar al-Bashir in power, whether to serve their own goals of curbing migration or maintaining a base for military personnel in the case of the US. Others note that neighbouring countries such as Egypt have their own repressive policies to consider.

Tame statements of “concern” by these powers are unlikely to be understood by al-Bashir as a precursor to any real action and are not meant to be. So who should the people of Sudan look to?

One possible answer is nobody at all. Sudan is used to fighting alone. Successful uprisings in 1964 and 1985 show the people have the strength to overthrow governments. Meanwhile, the size and longevity of the current protests prove al-Bashir’s regime has not been able to completely sap the vitality of resistance.

Still, the price of the struggle has been high and shows no signs of letting up. The state continues to imprison political leaders and activists and use deadly force at will. Fighting alone comes at a cost.

Another option

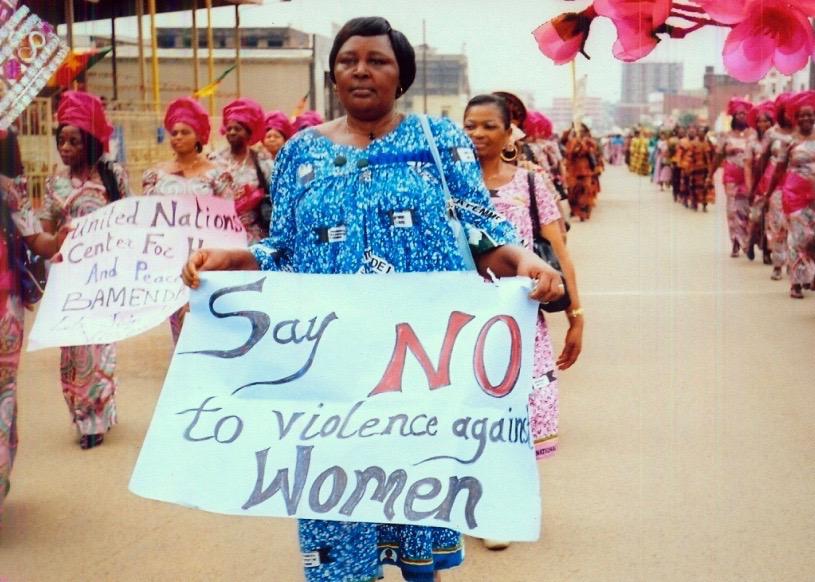

Both expending energy on attracting the attention of self-interested foreign governments and continuing alone are inadequate options, but there should others. Specifically, choices that draw on the promise of radical solidarities that reach across borders and cut out governments in favour of broader grassroots support. Choices that draw on African solidarities, Black solidarities, feminist solidarities, workers solidarities, and more. All of these political forces should be harnessed in Sudan, though doing so seems to require feats of political imagination that quickly appear idealistic.

The apparent dearth of international solidarity with Sudan is not because of a lack of political engagement on similar issues elsewhere. This is especially the case in Africa. The uprising in Sudan can be loosely categorised alongside a swell of protests that Adam Branch and Zachariah Mampilly call the “Third Wave” in the African Arguments book Africa Uprising.

These mobilisations have unsettled entrenched African regimes since the early-2000s. Responding to political repression and corruption, national and global inequalities, and the frequently insidious role of Western actors in propping up parasitic governments, these protest movements have significant elements in common despite vastly different histories and contexts. Today, for example, one can see similar dynamics to those in Sudan playing out in countries across the continent from Uganda in the east, to Zimbabwe in the south, to Togo in the west.

Counter-establishment movements outside Africa have also seen renewed energy in ways that also resonate with Sudan. The French gillettes jaunes have become a particularly visible symbol of the resounding calls for fundamental change across Europe. Meanwhile, Black Lives Matter in the US gained huge strength from 2014 as increasing attention was paid to the rate at which the police kill black men, women and children. This echoes clearly with the shared struggle in Sudan; pictures shared on Facebook and WhatsApp of boys and men killed by Sudanese security forces bring to mind the photos of Trayvon Martin, Michael Brown, Alton Sterling.

The case of Noura Hussein, initially sentenced to death last year for stabbing a man she had been forced to marry and who raped her, is simply the best-publicised of many similar cases. Once again, there are unsettling similarities to be found in many other countries where the law fails to protect survivors of sexual assault. This includes the US where women such as Cyntoia Brown are met with the full weight of the US carceral system for defending themselves against gender-based attacks.

Struggling with

It shouldn’t be surprising there are commonalities within movements for justice and freedom. Many of the forces at work here are global and interlinked. The violence of imperialism has not only wreaked havoc across the world, but is reflected in policies of labour extraction and the penalisation of vulnerable communities in their home countries.

The same logic of international capitalism that has devastated nations in the Global South has also broken up workers unions and increased levels of precarious labour in the North. Even the workings of patriarchy, often dismissed as a uniquely “cultural” phenomenon, are intertwined with the hierarchical rationalities of capital and empire.

None of this is to say that situations across the globe are identical or that different contexts do not often fundamentally change the meanings of struggle, its stakes and possibilities. The “echoes” of shared pain across borders and oceans are sometimes only that. Ignoring differences and attempting to struggle for rather than struggle with other oppressed populations has led to failures that have put many people off the idea as a whole. We are familiar, for example, with the critiques of attempts such as feminist Kate Millet’s misguided sojourn to Iran in which the concept of “global sisterhood” elided the needs of many of the women she claimed to be defending.

Solidarity even within borders can also be difficult. In Sudan, for instance, histories of marginalisation and violence against regions with predominantly racialised populations such as Darfur and the Nuba Mountains create gaps between the centre and peripheries that will require thoughtfully-constructed bridges.

Yet refusing to attempt solidarity for fear of misstep is itself a privileged position to hold.

Working towards solidarity is always a process rather than a state of being. Its many previous failures mean new attempts require a lot of political imagination, but what better time to harness those imaginations than during uprising, when the possibility of something better provides the strength needed to withstand violent oppression?

For those of us who are not Sudanese or who live outside Sudan, the uprisings might seem hard to reach. But some of the tools we need to practice solidarity are already in our grasp. Activists take huge risks sharing information widely and instantaneously over social media; the efforts of governments to restrict internet access shows how seriously it takes this threat. We can start by using the opportunity this information provides to pay closer attention to the issues that connect us; to increase our understanding of the histories that shaped them; and to begin imagining trans-national solutions that don’t rely on politically-motivated aid packages.

The interconnected nature of the world means that ignoring the need for trans-national struggle is not an option. The long-term success of the uprisings in Sudan will depend in part on the state of the world as a whole.

Meanwhile, the Sudanese protests’ fate will in turn have global repercussions, the extents of which are unknowable today. At the very least, they will push the limits of the possible, either for freedom movements or for oppressors. Recognising this fact should be enough to convince us that although Sudan continues to struggle alone, we shouldn’t let it.