I was born and raised on the South Side of Chicago, and I never thought about Confederate monuments during my childhood. I did not grow up walking past them every day, or reflect on how it must have felt to do so. I never put much thought into the meaning of monuments at all, because the ones I saw all looked alike to me ― dead white men on horses. What did they have to do with me? They did not reflect me or my experience. They did not reflect my reality, or that of anyone I was close to.

I grew up surrounded by what Bryan Stevenson of Equal Justice Initiative has called “refugees” from the South ― black people who fled the oppressive laws and overt injustice and deep racial inequality there. The people who filled my world shared stories about how hard life was in the South. For a child growing up in the North, the South seemed scary, especially since I came of age after the gruesome murder of Emmett Till. Till, like so many black children I grew up with, went “down South” to visit relatives ― but he never came back. He was from Chicago, too, and his story haunted me and the families around me.

Since 2008, I have been working to have a monument created to honor my great-grandmother, the investigative journalist and anti-lynching activist Ida B. Wells. In the United States, when it comes to representation in marble and metal, there is an incredible disparity. White men make up approximately 30 percent of the population, but over 90 percent of our statues and monuments are in white men’s images.

There are numerous statues to Robert E. Lee, Jefferson Davis, Stonewall Jackson and Nathan Bedford Forrest ― all leaders of the Confederacy. In contrast, I found just one statue apiece of women of color like Fannie Lou Hamer, Althea Gibson, Billie Holiday and a handful of other African-American women. Wells, an investigative journalism pioneer who exposed the realities of lynching and spent her life fighting for justice and equality, is set to get her first monument in 2019.

Last summer’s “Unite the Right” rally in Charlottesville, Virginia, was purportedly about preventing the removal of one of many monuments to Robert E. Lee. It turned into a horror show: White supremacists marched through town carrying torches to express their feelings of being disenfranchised. They killed a woman. The prospect of even one statue coming down was enough to spark a march that resembled the night riders prevalent during my ancestors’ time.

It made me question why the saving of one monument to a dead white man was such a point of contention for a group of white men whose existence is validated, and whose likenesses are reflected, in every crevice of our society. Why would the removal of one monument among several hundred feel like such a threat?

Monuments and statues are a way to document history in public spaces. Seeing monuments that reflect your image serves to validate who you are. When you don’t see monuments that look like you, it’s easy to not even pay attention to them, because there is no emotional connection. It’s just another thing that has nothing to do with you.

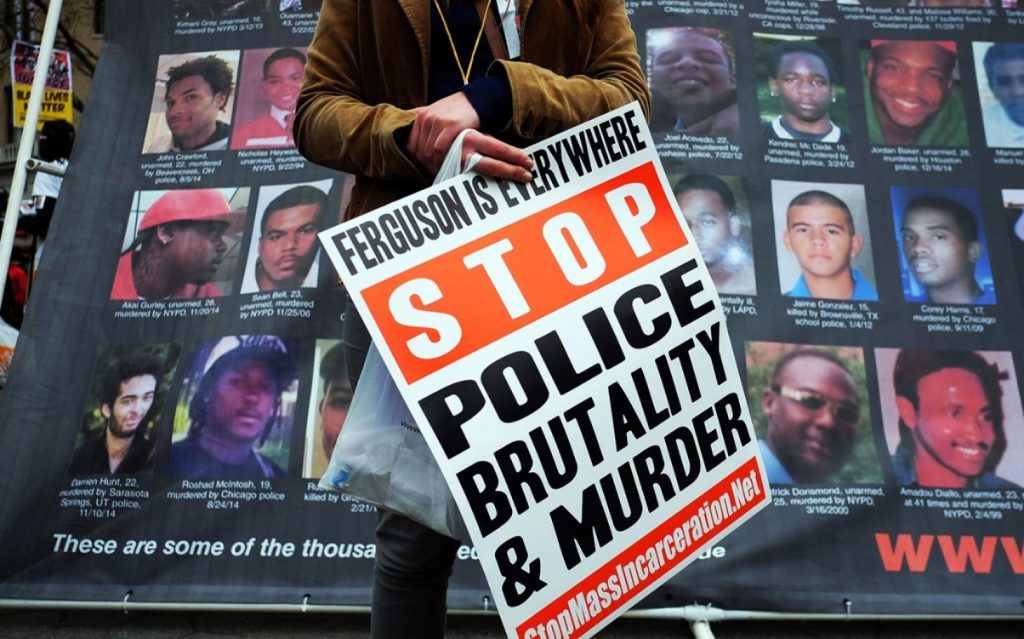

This country boasts almost 800 Confederate monuments, which are in the image of white men. The great majority of the wealth and power in this country is in the hands of white men. And yet despite all their power, the white men who descended on Charlottesville were enraged by the removal of just one monument, threatened by the idea that their needs, their voices and their image (even in monument form) might not be reflected in 100 percent of America’s public and cultural spaces. And they decided to make their voices heard by terrorizing entire communities that don’t look like them.

What is the effect of having your image reflected in public spaces? Whose stories are being told and whose are being ignored? What is being celebrated, and what is being erased? Statues are a reflection of what we are, and what we are is much more than white Confederate men.

As hard as it might be for white men to accept, almost 40 percent of this country is non-white. It is time for white men to recognize that Confederate monuments do not reflect the true history or racial makeup of this country. They are a tribute to a false narrative about the U.S. and its history that has been perpetuated for generations.

The disproportionate representation of white men, and the extreme underrepresentation of women and minorities, has contributed to a skewed and incomplete view of who built and shaped this country. Until America’s diversity is accurately reflected in every area of our society, including our statues and monuments, we will not be whole.