When Vincent Bollore arrived in Cameroon two years ago to meet with Paul Biya, Africa’s second-longest serving head of state, the presidential guard escorted him from his private jet to the state house.

The billionaire French businessman emerged after an hour, beaming, to tell reporters about investments he was making in the country, including in railways, a major port and a chain of movie theaters. Then, he was off.

Photographer: Zakaria Abdelkafi/AFP via Getty Images

For decades, that was Bollore’s modus operandi, and that of a generation of older French businessmen: cultivate personal ties with African leaders, mirroring France’s cosy relationships with its former colonies, and receive lucrative contracts and deals. While recent French presidents have vowed to do away with the shadowy network of money and power widely known as Francafrique, business hasn’t slowed down.

But Bollore’s way may be in jeopardy. After operating almost unchallenged in West Africa for more than 20 years, he was brought in for questioning by French judicial police Tuesday as part of a probe into possible bribes of public officials in Guinea and Togo. Wednesday, he was charged and released.

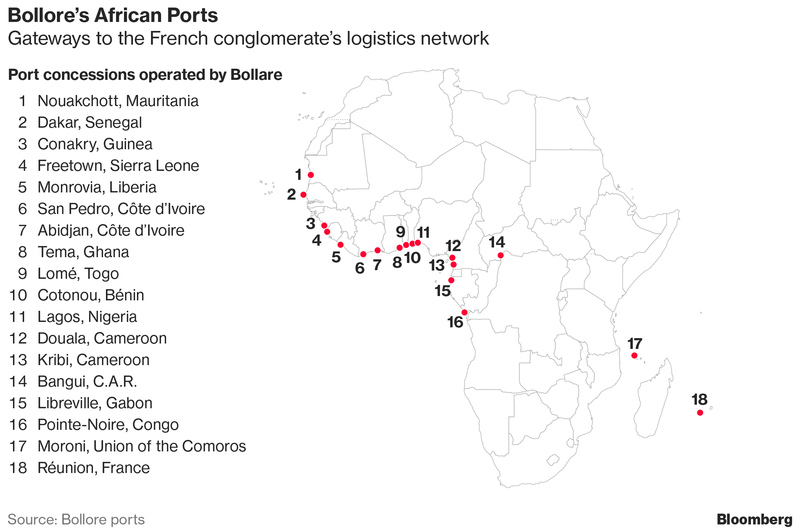

The investigation focuses on whether an advertising and media consulting company controlled by Bollore Group was used to facilitate getting port management contracts for Bollore’s Africa logistics unit. The media company ran the election campaign of Alpha Conde, who won Guinea’s 2010 presidential vote. Within months of assuming office, Conde had the operators of the Conakry port evicted by the military and the contract was given to Bollore’s Africa company.

As for Togo, investigators suspect the company’s services in the election of Faure Gnassingbe the same year were billed at a lower price than they should have in exchange for a similar port contract in Lome, according to a person familiar with the matter.

“Allegations of meddling by French politicians and businesspeople in West Africa has been a narrative that’s marked France’s interventions in these countries since the colonial era,” said Liesl Louw-Vaudran, senior researcher at the Institute for Security Studies in Pretoria, South Africa. “The rules are certainly changing. People have closed their eyes to the accusations of corruption surrounding Bollore for such a long time that it’s good to know that finally, some judicial process has started.”

Photographer: Steve Jordan/AFP via Getty Images

The Bollore Group said in a statement that it “formally denies” that its African company did anything irregular, while saying it is the target of an investigation over billing for communications services in Guinea and Togo in 2009 and 2010. The media company, now called Havas, “has always operated with irreproachable transparency.” After Bollore was charged, the company said he and his defense team will have access to the case file underpinning the allegations for the first time and “will have the opportunity to respond to these unfounded accusations.”

Guinea has repeatedly said the awarding of the port concession was legal. Still, Guinea was ordered by an arbitration court to pay 38.5 million euros ($47 million) to the evicted port managers, according to court documents. The government didn’t respond to requests for comment on the French case. Neither did the Togolese government.

The African business environment has changed since Bollore first began investing there in the 1980s. Investors and companies from China, India and Turkey have started doing more commerce on the continent, undermining French dominance in West Africa. At the same time, President Emmanuel Macron has gone farther than his predecessors in denouncing France’s past political interference, telling students in Burkina Faso a few months ago that the country’s colonial past should no longer color relations.

The probe into Bollore’s dealings also fits into a global push for more transparency in business and politics, following high-profile exposures of corruption and fraud such as in Wikileaks and the Panama Papers. Last year, a French court handed a suspended jail term to the son of Equatorial Guinea’s leader after convicting him of using state funds to buy real estate in Paris and luxury cars.

“The problems of Bollore in Africa show that France is getting out of a historical anachronism,” said Antoine Glaser, author of multiple books over several decades about France’s activities in Africa. “It’s lasted for a long time because some African presidents were under the sway of France for many years and were still in office. But there’s a feeling that we’re heading toward a more globalized Africa.”

Bollore, 66, built a conglomerate worth $15 billion in part by acquiring a near-monopoly on ports and logistics in West and central Africa. His empire, which runs almost all the main seaports in the region as well as several dry ports, airports and railroads, also extends to palm-oil plantations, marketing companies and television.

Africa accounts for 23 percent of company revenue. Outside Africa, Bollore owns stakes in Vivendi SA, Universal Music, pay-TV channel Canal Plus and Telecom Italia SpA, among others. Among his close friends: former French President Nicolas Sarkozy.

On the continent, Bollore fostered ties both with ex-Ivory Coast President Laurent Gbagbo and then with the man who defeated him in the 2010 election, Alassane Ouattara. Guinean President Alpha Conde and Republic of Congo President Denis Sassou Nguesso both call Bollore a friend. During the visit in Cameroon, Biya, 85, smiled widely as he embraced Bollore and kissed him on both cheeks.

Yet in recent years, Bollore has lost goodwill among some African leaders. Following a protracted legal dispute between Bollore and a Beninese competitor over the right to build and renovate a railway link between Benin and Niger, Benin President Patrice Talon said last month that he wants both companies to withdraw from the $4 billion project. China, he told Radio France Internationale, is much better placed to fund and build the railway.

Bollore Group didn’t respond to questions about how it operates in Africa.

Bollore still gets his way sometimes. A Cameroonian contract to develop and operate a container terminal at the Kribi port was awarded to a consortium led by his company—even though it had been excluded by a government commission from the shortlist of companies vying for the deal. And that happened even before Bollore’s 2016 meeting with President Biya.

Photographer: Issue Sanogo/AFP via Getty Images

In Ivory Coast, Bollore won a concession to build a container terminal despite objections from the World Bank about the transparency of the bidding process, before getting the contract for a second terminal in 2013, effectively obtaining a monopoly in the port of Abidjan. Competitors lodged a complaint with a regional authority, the West African Economic and Monetary Union, and the deal was criticized publicly by the country’s then-Minister of Commerce, Jean-Louis Billon.

“Bollore is the lord of transport in Ivory Coast,” he said. “I wonder why every time someone arrives in the tropics, he allows himself to do what he wouldn’t do at home.”

— With assistance by Gaspard Sebag, Samuel Dodge, Kossi Woussou, and Ougna Camara