Ecuador has dealt a blow to OPEC unity by announcing it will start raising oil production this month, arguing it needs the money.

OPEC has for years cheated on its own agreements, particularly when oil prices fail to recover after an output cut. But Ecuador has taken the rare step of saying publicly it will increase production, making it impossible for the group to conceal the desertion.

The Latin American country won’t be able to meet its commitment to lower output by 26,000 barrels a day to 522,000 a day, as agreed with OPEC last year, Oil Minister Carlos Perez said in an interview with Teleamazonas late Monday.

“There’s a need for funds for the fiscal treasury, hence we’ve taken the decision to gradually increase output,” Perez said. “What Ecuador does or doesn’t do has no major impact on OPEC output.”

Indeed, Ecuador’s exit is largely immaterial when considering the size of the global oil market, as the amount it agreed to cut accounts for less than 25 seconds of daily consumption. Still, it does create a dangerous precedent in the Organization of Petroleum Exporting Countries, opening the door for other, perhaps bigger producers to follow suit.

“Ecuador’s latest statement will not matter for global balances but it shows the challenges for OPEC members given the cuts failed to raise prices,” said Amrita Sen, chief oil analyst at London-based Energy Aspects Ltd. The announcement may “again give rise to fears of the deal falling apart,” she said.

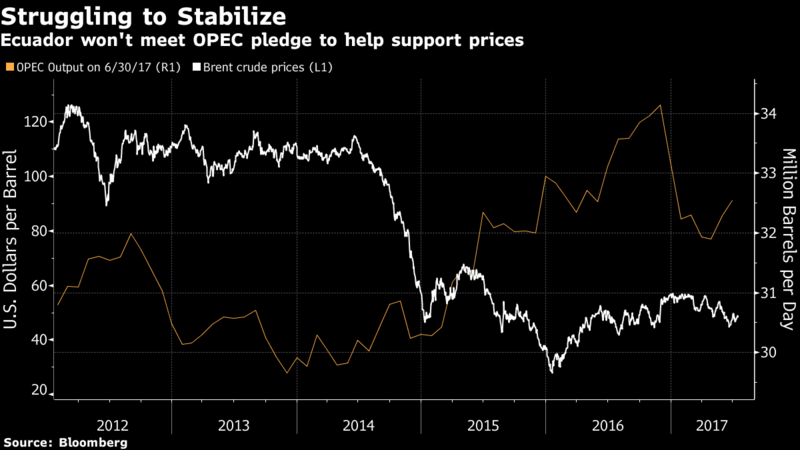

Benchmark Brent crude has erased most of the gains it made after OPEC’s November deal, dropping 14 percent this year to trade below $49 a barrel on Tuesday.

Ecuador says it had a “non-written” agreement with OPEC that gave it flexibility on output because of its fiscal needs. The Vienna-based group, however, hasn’t disclosed such an accord.

Ecuador isn’t the only OPEC member struggling to bolster its finances, with others such as Algeria also relying heavily on petrodollar reserves built up during the 2000-2008 oil-price boom to plug fiscal deficits. Many require prices significantly higher than today’s level to balance the books, according to non-partisan New York think-tank the Council on Foreign Relations.

Other small OPEC members may now argue they also need extra money, said Torbjorn Kjus, an analyst at DNB Bank ASA in Oslo.

“They should understand that this might hurt the whole deal,” he said, suggesting OPEC’s top producer Saudi Arabia could decide: “If you guys don’t want to participate then let’s just dump the oil price down into the $20s and see how funny that is.”

OPEC’s implementation of its deal to curtail output is slipping after a strong start earlier this year. The International Energy Agency put compliance at 78 percent in June, a six-month low, as Iraq, the United Arab Emirates, Ecuador and Venezuela pumped more than agreed. Iraq produced 4.5 million barrels a day, meeting just 29 percent of its commitment.

Ecuador, OPEC’s third-smallest member by production after Equatorial Guinea and Gabon, is now pumping close to 545,000 barrels a day from its oil fields in the Amazon rainforest, Perez said in the interview. That’s not far off the 548,000 barrels a day it produced before the OPEC deal kicked in.

OPEC and several non-member countries agreed to curb output by almost 1.8 million barrels a day, starting in January, to reduce global inventories and boost prices. So far the group, led by Saudi Arabia and Russia, has achieved little, with stocks well above the five-year average, in part due to rising U.S. shale supply.