Nigeria’s latest attempt to ease the dollar shortage choking its economy is dependent on traders trusting the central bank.

The monetary authority opened a foreign-exchange window for investors and exporters Monday where the naira trades between the interbank rate and the black-market rate, which many Nigerians use to access dollars. In the weeks before the opening, Governor Godwin Emefiele told senior bankers that he would tolerate a weaker naira and allow the market to determine the rate within the new window, according to a person who attended the meetings.

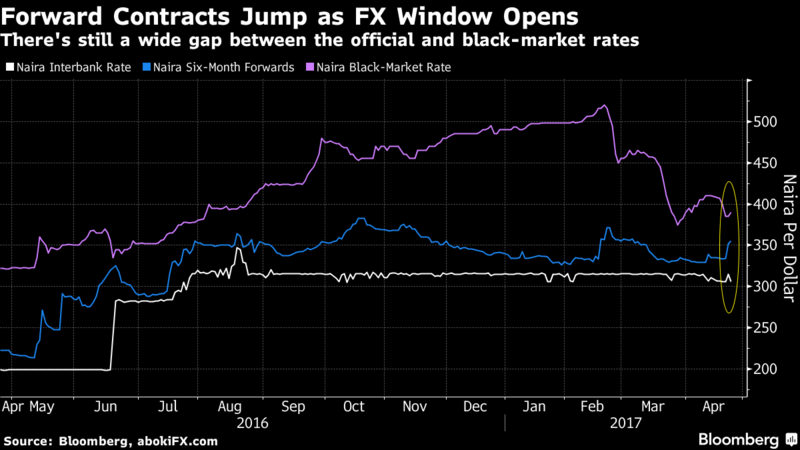

While the initial market reaction showed investors are optimistic the platform will be successful in bringing hard currency into Nigeria — bank stocks rose and naira forward contracts priced in a weaker currency — policy makers still must demonstrate that they’ll allow free trading. Investors have been disappointed before.

Last June, the central bank ended a 16-month currency-peg and promised to float the naira, but it has traded near 315 per dollar since August. That’s more than 20 percent stronger than its black-market price of 388.

“If this is going to be market-determined, that would be a great positive,” said Razia Khan, the chief Africa economist at Standard Chartered Plc in London. “Given the false start we had in June last year, there’ll be a certain amount of caution initially.”

Standard Bank Group Ltd. analysts expect a “sharp but unsustainable” decline in the naira as investors and companies try to clear their unmet demand for dollars of about $4 billion. If that happens, the central bank may start manipulating the rate again, which would discourage inflows.

“What is on paper may not actually be what is practiced,” Standard Bank’s Lagos-based Ayomide Mejabi and Phumelele Mbiyo in Johannesburg said in a note Monday.

What’s Happened?

Unlike Egypt, which floated its pound in November when it was also desperate for hard currency, Nigeria’s central bank has introduced multiple exchange rates and sold forward contracts to meet demand for dollars. But those measures haven’t diminished the need for a black market to buy the greenback.

The central bank says the separate window will help “deepen the foreign exchange market and accommodate all foreign-exchange obligations.” Those allowed to sell dollars include portfolio investors, exporters, banks and the regulator itself. Though trades are meant to be done on a willing-buyer, willing-seller basis, the central bank says it can intervene.

The FMDQ OTC Securities Exchange, a Lagos-based trading platform, will publish daily rates based on a poll of banks, with Monday’s closing rate set at 377.1 per dollar.

Why Did the Central Bank do This?

Nigeria has suffered from a dearth of foreign exchange since the price of oil, its main export, plunged in 2014. The central bank’s imposition of capital controls and a currency peg only worsened the crisis, according to investors, who have pulled money out of the country in the past two years. The government and central bank need them back to revive the economy, which shrank last year for the first time since 1991.

“There was acknowledgment from policy makers that greater flexibility in the FX regime was needed and that the existing system was hurting growth,” Khan said.

Will it Work?

Traders would prefer Emefiele to free the existing interbank market rather than create a separate exchange rate. But JPMorgan Asset Management says investors may be enticed into the market if they’re confident there’s enough liquidity for them to exit.

“It’s early days to gauge how effective the new window will be,” Diana Kiluta, an emerging markets debt portfolio manager at JPMorgan Asset Management in London, said in an emailed response to questions. “If indeed foreign investor flows can consistently clear in the window and there is some transparency around price determination, this could begin to restore some confidence.”

What are the Dangers?

Nigeria’s President Muhammadu Buhari and Emefiele have consistently criticized those calling for a weaker naira, saying it would only accelerate inflation already at 17 percent and hurt the poor. That’s fueling investor skepticism that the central bank will allow a true float within the window.

Another danger is that it’s unclear whether oil companies, which generate the bulk of Nigeria’s export earnings, will be able to sell dollars in the window. Without them, the central bank may be left as the main supplier until foreign investors return.

“There are a number of things that need clarification,” Khan said.