Like many parents, financial adviser Dennis Ryan has two daughters with starkly different personalities. Emma, 18, is introverted and intellectual, and she hated competitive sports as a young child. “She was the kid in left field with the glove on her head picking dandelions,” he says. Annie, 15, is the polar opposite: She’s incredibly social, a leader among her friends and always glued to her cellphone. “She never wants to miss a single text or Instagram post,” Ryan says.

He has paid close attention to his daughters’ contrasting personalities as they’ve grown older. He inspired Emma to participate in the Latin club and charity work, while he encouraged Annie to take advantage of what he calls her “gift of gab” by using her popularity to be a positive leader among her friends.

Ryan’s parenting style is a prime example of what Lea Waters, Ph.D., head of the Positive Psychology Centre at the University of Melbourne, calls strength-based parenting: an approach to parenting in which “parents place more of their focus and energy on the strengths, talents and positive qualities of their children, as compared to focusing their time and energy on fixing the faults, flaws and weaknesses in their kids.”

Strength-based parenting—which is fueled by the concepts of positive psychology—is still in the nascent stages of research, but many parents already do it subconsciously. Waters says the handful of scientific studies on the topic have shown it can help children become more successful as adults. Other valuable parenting techniques for raising well-rounded children include stressing the importance of soft skills, teaching children that failure is acceptable and inevitable, defining more broadly what it means to be smart and using the concepts of positive psychology to help children be happier.

Waters says most people were raised to believe the best way to improve a child is to fix what is wrong with him or her, when instead we should focus on nurturing his or her inherent strengths. Johnny isn’t good at math? Don’t drill it into him 24/7. Instead build on his natural talent for language by encouraging him to write short stories.

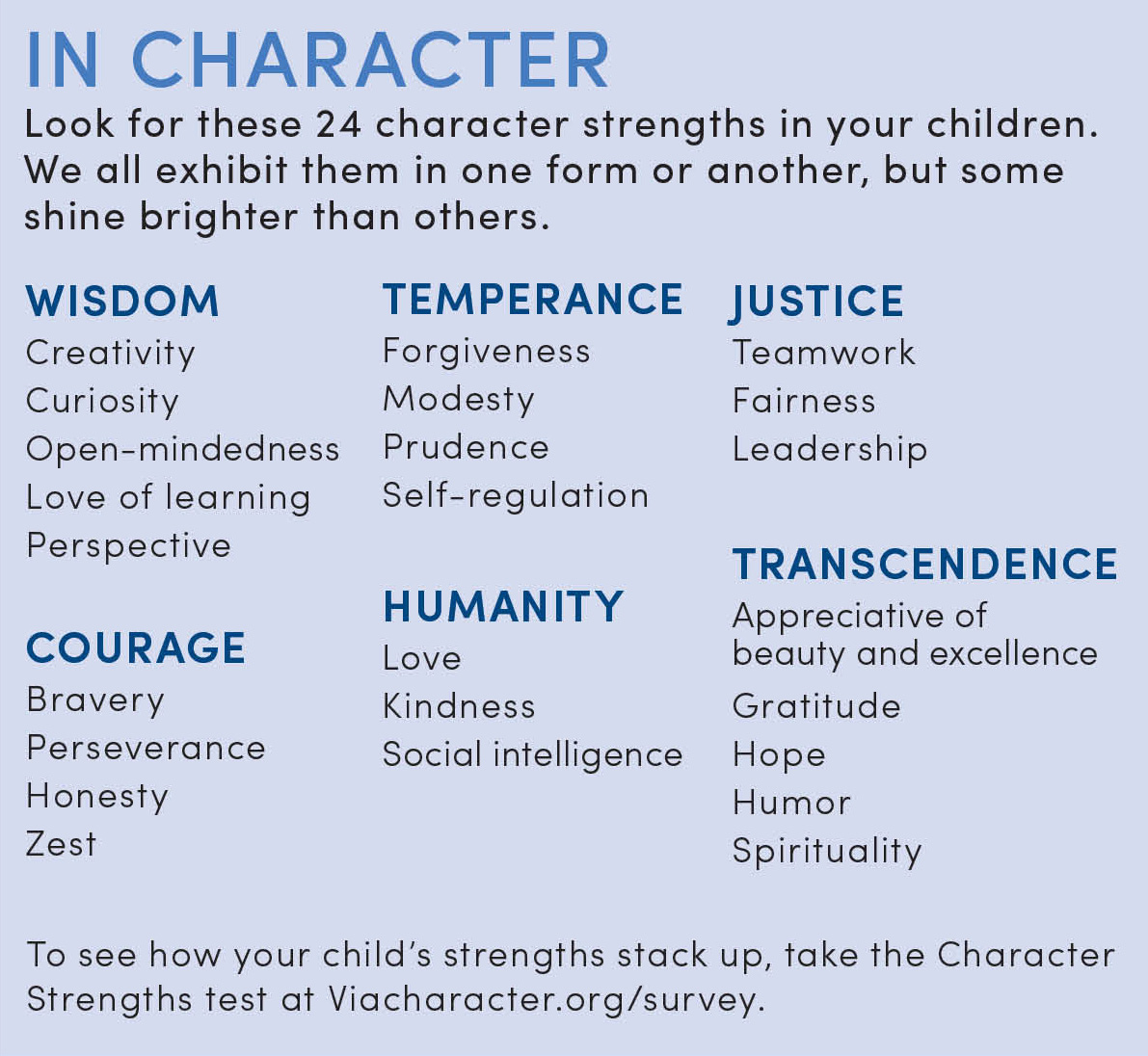

In attempting to fix our children’s’ flaws, Waters says, we think we’re doing the right thing, when instead “whether you mean it or not, you’re consistently and constantly telling your child, You’re not good enough. You are impatient. You don’t have good social skills. You’re uncoordinated.” Instead of fixing the negative qualities, improve upon your child’s naturally strong character strengths, such as kindness, grit, creativity and leadership.

The New Smart

Although strength-based parenting is imperative for raising conscientious, well-adjusted children, most parents also want their children to be considered smart. They want their children to flourish and fare better than they did—to score better on the SATs, to land a better job than they did, to go on to make more money than they do. Although raising children to be intelligent is crucial, it’s not enough. In today’s world, with so much competition for quality jobs and other jobs giving way to technology, prospective employers want candidates who are creative, deep thinkers, too. Happiness, grit, creativity, communication, courage and critical thinking are arguably more important for developing your child’s intelligence than being able to name the capitals of every state.

“It can’t be that everything can be reduced to your score on a narrowly construed bubble test.”

“It can’t be that everything can be reduced to your score on a narrowly construed bubble test,” says Kathy Hirsh-Pasek, co-author of Becoming Brilliant: What Science Tells Us About Raising Successful Children. “It has to be that success means more than just preparing our children in reading, writing and math.”

We need to redefine the word smart, says Roberta Michnick Golinkoff, co-author of Becoming Brilliant. “While you want your children to do well in school, it’s not enough. We want parents to know there is nothing wrong with wanting your kids to be successful personally and to have happy and well-adjusted lives.”

Important as it might be, being considered smart won’t necessarily mean a child goes on to have a happy, well-adjusted adult life. “Education means not cramming people with meaningless facts they regurgitate in exams,” said Sir Anthony Seldon, one of the leading proponents of positive psychology, at the International Positive Education Network’s (IPEN) inaugural Festival of Positive Education held this past July. “Transformative, real education is about drawing out what is inside—those multiple attitudes and intelligences.”

Traditionally called soft skills, abilities such as communication, teamwork, adaptability and time management are just as important to a child’s success in school and life as anything else, Hirsh-Pasek says. “I’m trying to put a bullet through hard and soft skills,” she says, “because I think rather than demeaning some of these skills that are so important and so foundational, we should begin to understand that there really is a breadth of skills all kids need if they’re going to succeed and be happy kids in the present and then be good, collaborative, thinking, smart people in the future.”

Learning to Fail

One of the most prevalent problems plaguing today’s society is our “one-answer culture,” Golinkoff says, because when children fail, “they really fail.” A dyslexic child may do dismally on the SATs and be deemed unintelligent, when in fact he or she may exhibit some of the character strengths inherent in dyslexic people, such as creativity and high emotional intelligence. We need to teach children that there are multiple ways to be smart.

Hirsh-Pasek stresses the importance of allowing young children to tinker and explore, because in exercising their creativity, “one of our kids might just develop the next iPad or the cure for cancer.”

In teaching children to fail, we can also allow them to hone in on their unique skill set. Children start out with an I-can-do-anything attitude in preschool, Golinkoff says, and if they don’t grow out of this phase, they won’t develop their specific talents and skill sets. Don’t tell your daughter she’s a natural swimmer if she’s not. Instead, try to strengthen her natural gift for leadership or compassion.

The Happiness Factor

Catering to your child’s character strengths, teaching him or her how to fail and instilling in your child the skills necessary to be intelligent in today’s society are all important. But the most important quality, the most necessary component for raising a child, is ensuring he or she is happy. Raising children with the tenets of positive psychology and developing their happiness at all times is the secret weapon for effective parenting.

“Having a positive mindset is one of the greatest competitive advantages we can give somebody,” positive psychologist Shawn Achor, “The Happiness Guy” for SUCCESS, said at IPEN’s Festival of Positive Education. “I think we’re afraid of happiness as a society,” he says. People think if they’re too happy, they won’t be hungry enough for success. But by positively supporting children during the learning process, they can reach higher levels of happiness and in turn be more successful in school.

He says one way we can help our children is by shifting the thought process from If I work harder, I’ll be more successful and I’ll be happier to If I’m happy, I’ll work harder and I’ll be more successful.

At the end of the day, we cannot prevent the inevitable failures and setbacks our children will face. But we can arm them with the tools to remain resilient no matter what happens.

“We cannot help our children from bad things happening to them,” Seldon says. “Bad things will happen to us in our lives. But if we do these things—if we give young people the best possible character, education, virtue, skills and positive psychology approaches—it will give them the optimal chance to be able to cope with it.”