In Africa, as in Cuba, the late Fidel Castro was both loved and despised.

Yibrah Mehari thinks of Castro as a benefactor. After his father, an Ethiopian soldier, died in 1971, Mehari was sent to Cuba at age 14 and educated there through his post-graduate years, becoming a successful architect.

Mehari says he and thousands of other Ethiopians educated in Cuba have “tremendous love” for Castro. “Like a father, he used to come to visit our school and encourage us to do well,” he told VOA’s Horn of Africa service Monday. “We felt at home in Cuba, never isolated or felt [like] outsiders.”

Angola

Jonuel Goncalves thinks of Castro as a war hawk. Goncalves is a political analyst in Angola, a country where Castro sent more than 20,000 troops in 1975 to back the Marxist MPLA in Angola’s civil war. He also deployed troops to support leftist governments in Mozambique and Ethiopia.

The interventions, backed by the Soviet Union, “transformed Africa into a Cold War battlefield,” Goncalves says. And, he notes, “The countries that benefited from the presence of Cuban soldiers had to pay for those soldiers.”

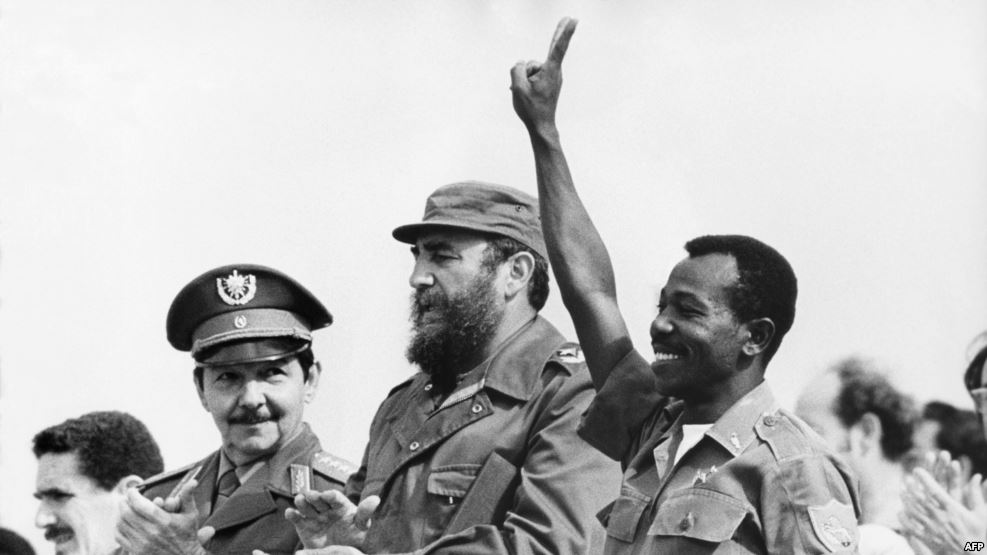

In all, Castro leaves a complicated legacy in Africa. Many on the continent will remember him as a key ally to African independence movements, and as a generous man who provided doctors and teachers to poor societies.

Those views, however, are far from universal. Perhaps the one thing all observers agree on is that Fidel Castro made a deep, lasting impact on Africa as the continent shook off the yoke of colonialism.

“As you know, and this is well documented, you cannot write the history of Africa or Cuba without Castro,” says Erastus Mwencha, the deputy chair of the African Union Commission.

Africa libre

Mwencha, a Kenyan, says Africa’s independence movements from the 1960s onward knew they had a comrade in the Cuban ruler, who, from the start, preached a type of liberation theology and practiced what he preached.

“It started with the DRC, with Patrice Lumumba, and continued until the liberation of South Africa from apartheid,” he says. “Cuba, through Castro, gave resources, gave soldiers, trained combatants, and did everything it could to assist Africa [and] gain independence.”

That spirit of assistance continued after Castro ceded power to his brother, Raul, Mwencha notes. “Most recently, when we had the problem of Ebola, Cuba was one of those countries, challenged as it is under sanctions, that sent doctors and did everything that they could to assist the countries that were affected.”

A former chair of the AU commission, Salim Ahmed Salim, was once Tanzania’s ambassador to Cuba and carries a positive, albeit balanced, view of Castro.

“He improved the lives of his people but at the same time helped neighboring and African countries during the liberation struggle and sending doctors, teachers, scientists and military assistance to countries like Tanzania and Namibia,” he says. “Yes, there are a lot of things that did not go well on liberty of expression and other forms of freedoms, but when we talk about social and economic development, there is a lot to learn from and follow.”

Military muscle to leftists

Castro’s intervention — some would call it interference — in Africa’s affairs, stemmed from his strong communist beliefs, a need for economic partners abroad and his alliance with the Soviet Union during the Cold War.

For years, Cuba was one of the chief supporters of the MPLA in Angola, supplying tens of thousands of troops to bolster the movement as it seized and held power. In return, Angola paid Cuba hundreds of millions of dollars from oil export revenues.

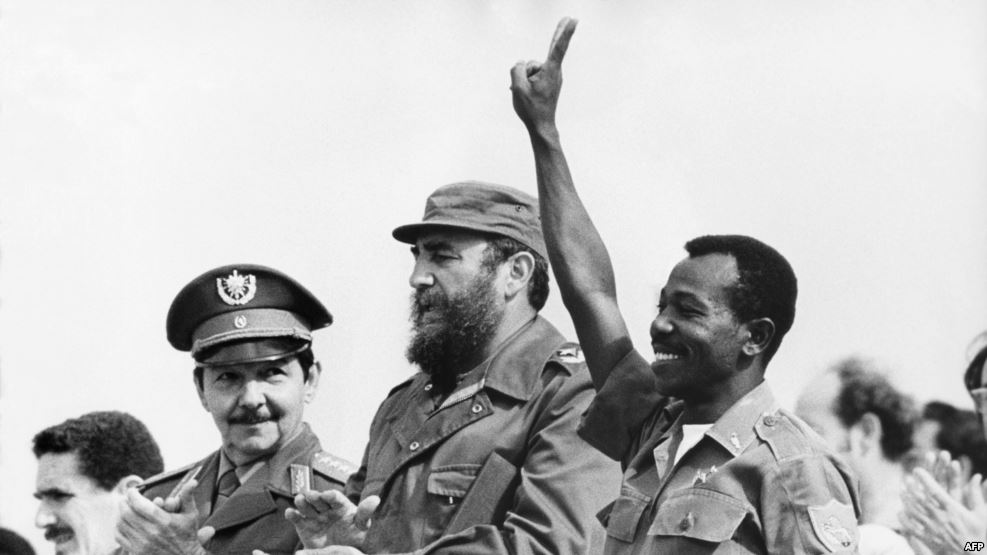

In the mid-1970s, Cuba supplied troops to support Mozambique’s ruling FRELIMO party and the government of Mengistu Haile Mariam of Ethiopia. The intervention in Ethiopia was especially forceful, a deployment of 15,000 troops after Somalia launched a 1977 offensive to capture the Ogaden region, which has an ethnic Somali majority.

Before the offensive, Castro visited the region and tried to enlist Ethiopia, Somalia and Yemen in a socialist federation. “We told him that this is about the self-determination of people and if this federation is going to unite ethnic Somalis, we are up for it,” says former Somali Deputy Defense Minister Mohamed Nur Galal.

After Somalia attacked, Cuba and the Soviets sided with Ethiopia. By March 1978, Somali troops suffered heavy defeats and were driven back to where they started the offensive.

Not surprisingly, Castro is not remembered fondly in Somalia today.

“I read a book Castro wrote, saying he brought Somalia to its knees,” says Galal. “He was a bad man who hated Somalis.”

Not forgotten

Castro’s influence in Africa greatly declined but did not entirely vanish after the Soviet Union collapsed, costing Cuba its main economic sponsor and plunging the country into a wrenching depression.

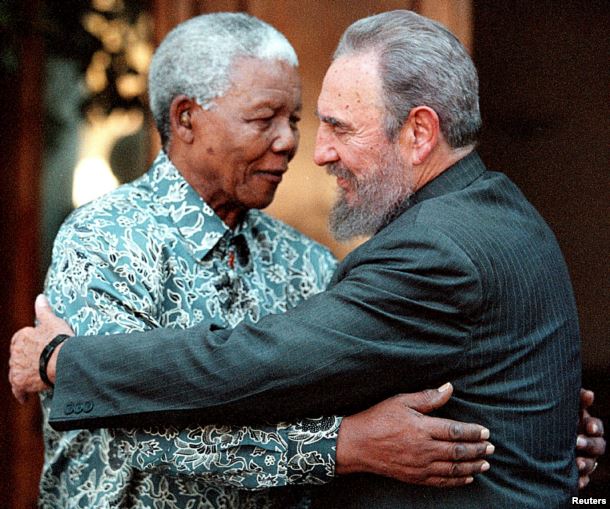

In the 1990s, Cuba offered to help South Africa with its AIDS epidemic by providing cheap drugs. In 1998, Castro visited Johannesburg, where he met with President Nelson Mandela and was given a state dinner in thanks for his support of the anti-apartheid movement.

When Castro is laid to rest in Cuba on December 4, there will no doubt be an assortment of current and past African leaders on hand, saying goodbye to a man that many, though not all, considered a friend.

VOA’s English to Africa, Portuguese to Africa, Horn of Africa, Swahili and Somali Services contributed to this article