Jessica Bennett, in conversation at AOL’s BUILD series. (Photo by Matthew Eisman/Getty Images)

A man interrupts you as you’re trying to explain an idea at work. You sit down at a meeting only to be told by a male superior that you’re best suited to take notes. You somehow are always the one who gets stuck organizing the office birthday party and running around trying to find good cupcakes. You worry that asking for a raise will come off as selfish or greedy or entitled.

Each one of these situations is an example of subtle sexism in the workplace. Taken in isolation, none of these things are life ruiners. But add them all together? You’re looking at a long career full of wage losses, “mommy tracking,” men getting credit for women’s ideas, and women pitted against each other for the last seat at the table.

So, what’s a girl… er… woman, to do? According to journalist and author Jessica Bennett, the key is to think small, even while we’re working to smash the larger patriarchy. And starting a Feminist Fight Club ― essentially, a collective of women (and some good men) who share tips and tricks for how to go about this practical patriarchal takedown ― is one way to start.

We talked to Bennett at AOL’s BUILD Series (video below) about her new book, Feminist Fight Club: An Office Survival Manual For A Sexist Workplace, her real-life Feminist Fight Club, and how Donald Trump is the ultimate professional sexist.

“We fight patriarchy, not each other.”

What exactly is a Feminist Fight Club?

I’m in a real Feminist Fight Club, and it was the inspiration for the book. We fight patriarchy, not each other.

It’s a group of women I’ve been meeting with since I began my career about 10 years ago. We were all in really junior-level positions. I was a junior reporter at Newsweek. We all started butting up against what we would learn was sexism, but at the time we just thought, “Is this us? Do we just have shitty ideas?” We began meeting monthly at one of our members’ parents’ house ― because all of our apartments were too small ― and we would gather and talk about our jobs, talk about the challenges we faced. We would try to share tricks and tips. And it still exists! We still meet!

At what point did your individual Feminist Fight Club turn into the idea for this book?

The first rule of the club was that we didn’t talk about the club outside of the club. It was tongue-in-cheek, but some of us were in jobs where we didn’t feel comfortable having it be public that we were in a feminist consciousness-raising club. In the book, the club is still anonymous, but I talk more broadly about the tools we’ve used over the years and the tricks we’ve learned.

We talk so much about issues of gender inequity, but there’s not always a lot of solutions.

So I wanted to tell the story of this group I’d been involved in, but, also, we talk so much about issues of gender inequity, but there’s not always a lot of solutions. [Let’s say] I’m 24 and I’m just starting my career. It can feel pretty powerless to be dealing with some of this stuff, and your only recourse is to write your local Congressperson. So I wanted to combine a hipster handbook-style Mortal Kombat with research about how we can fight gender bias.

What are the minutiae of subtle sexism that this book is aiming to offer solutions to?

It’s not rocket science, and sometimes it almost sounds silly. Taken individually, a man interrupting you when you speak, or somebody saying, “Is it that time of the month?,” or having an idea you put forward attributed to somebody else, can sound small. I’ve heard it referred to as “death by a thousand cuts.” [It all] adds up over time, so that’s what I’m trying to tackle.

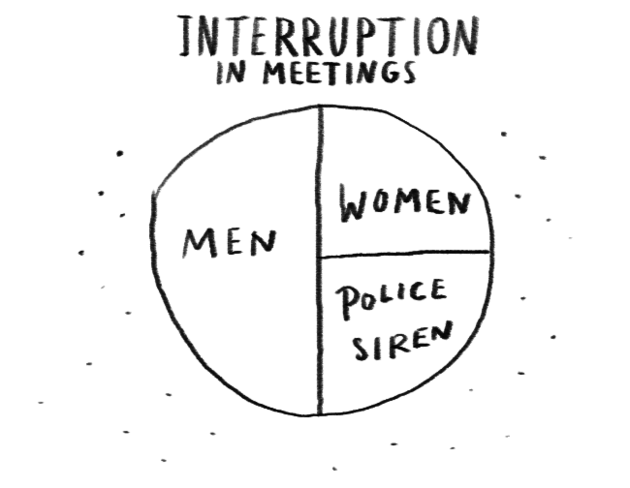

By creating these silly names for things, like the Manterruptor ― obviously, not every man is an interruptor, and not every interruptor is a man. It’s meant to be tongue-in-cheek. But women are interrupted at twice the rate of men, so there’s truth behind it. Just like mansplaining has allowed us to call out behavior that has existed arguably since the dawn of time, I think that these funny phrases can actually allow us to talk about really complicated issues.

So are there any moves from this guide that can help tackle a bully in the workplace ― or on a larger scale, like, maybe, a Donald Trump?

Donald Trump is sort of like a caricature of all of these things in the book. Like, the Menstruhater, which is the guy who every time you express an opinion goes, “Is it that time of the month?” Or the Lacthater, which is the man or woman who thinks that because you’re pregnant or breastfeeding or may some day get pregnant, you clearly can’t do your job.

Statistics can be your verbal karate. Anytime somebody tries to argue against this stuff, I just try to hit them with data.

Some of the tactics [to fight these things] are silly. Like, if somebody says, “Is it that time of the month?” You can say, “Yeah, it’s the time of the month where I’m about to do your performance review, and you’re screwed.” Or you can hit people back with research. I always find data to be very effective in shutting down an argument against it. So with the Lacthater, you can present research that shows moms do get shit done faster and more efficiently than people without children. They don’t have time to deal with crap.

Statistics can be your verbal karate. Anytime somebody tries to argue against this stuff, I just try to hit them with data.

You also touch on gendered language in the book ― words like “bitchy” or “aggressive” or “crazy,” which are used to describe professional women, but not their male counterparts. How does this language impact women on a larger scale?

These are double standards that women face. Hillary Clinton is obviously assertive, but she’s also referred to as aggressive. She’s often referred to as ambitious ― but not in a good way, in a pathological way. She’s a person running for president. Of course she’s ambitious. But what the research has shown is that these words can actually undermine women. And there was one study from the Women’s Media Center that found such language actually makes people less likely to vote for or support a candidate.

So, words actually do really have power. Like, “shrill.” Shrill is a word that’s twice as likely to be used in the media to refer to a female voice as a male voice. This is what I mean by the subtlety of things. Perceiving a woman as bossy when she makes a demand. Would you ever call a man bossy? Probably not. But don’t you want female leaders to make demands? That’s the requirements of the job. So some of this is as simple as watching our language when it comes to the way we talk about women.

And holding the media accountable.

Yeah! And checking ourselves. A lot of this is unconscious behavior. And men exhibit it, but so do women. I’ve caught myself doing that very same thing. And [it’s important to] take a moment to acknowledge it and realize it, so you can correct the behavior.

You actually have an entire section of the book that addresses the ways women unintentionally undermine themselves. Can you speak to that?

There’s been this argument for a long time in feminist circles when it comes to women undermining themselves. By asking women to correct those problems, are we actually putting the onus on them? [Are we saying] it’s their fault? And my feeling is, all of these things exist because we exist in a larger patriarchal society where men have ruled. So over time, we’ve been taught that our voices are not as important and we’ve learned to come off as humble. And men don’t face these things.

My intention here is not to tell women they need to change their behavior, but that there are these really simple things we can do in the day to day.

In one sense, to overcome that, we need to push back against it. We need to learn how to brag, we need to learn to self-promote. There’s this thing called Impostor Syndrome, when women or people of color or anybody who has the pressure of accomplishing a first feels like they don’t really belong. So there are some simple things a person can do to overcome that. One of them is power-posing ― you stand in a wide-stance Wonder Woman pose, there’s a famous TED talk about it ― and you stand there for 90 seconds and your testosterone levels go up, your stress levels go down and your confidence is raised. I’ve done it. I feel like an idiot while I’m doing it, but I’ve used it for pitch meetings, I’ve used it for speeches, I used it for a breakup once. And it can be really effective.

My intention here is not to tell women they need to change their behavior, but that there are these really simple things we can do in the day to day, while also fighting against structures.

At one point, you cheekily suggest that we all learn to carry ourselves with the confidence of a mediocre white man. What about that mediocre white man are we trying to emulate?

I didn’t come up with the phrase, “carry yourself with the confidence of a mediocre white man,” but I used to share a wall at Newsweek with a very confident white man. I call him Josh in the book ― that’s not his real name ― but I would just observe him. I would observe the way he pitched stories, and I would observe the way that even when he had no clue what he was talking about, he delivered whatever he was saying with such confidence that the people in the room believed him. And I would be stumbling through this story idea that I had spent hours preparing for, but I didn’t have that confidence.

Over time, it almost became a joke among my colleagues. We’d be like, “What Would Josh Do? WWJD?” I’d literally ask myself going into a negotiation or into anything that made me stressed out or fearful, “What would Josh do? How do I try to mimic that behavior?” So I don’t think it’s about telling women to act like men ― it’s supposed to be a joke ― but, asking yourself what would a man do in a certain situation? That has worked for me.

So let’s talk a little bit about men. How can men join this conversation in a way that’s productive?

Humor is a really great way to open up these issues so that people don’t feel attacked. But also understanding that men are some of our greatest allies in this battle and there are a lot of really simple things they can do in the moment to help these issues:

(1) If you hear a woman being interrupted in a meeting repeatedly, you can interrupt the interruptor.

I think we need to recognize that men are actually amazing, amazing allies in this battle.

(2) You can give credit where it’s due. I’m not going to sit here and accuse men of taking credit for female ideas, though that has happened. But what the research shows is that female ideas are frequently attributed to men without them taking credit. We just assume that a great idea must have come from a man. So, what can a man do? He can correct that.

(3) If you’re in a hiring position, for every [white] man that you interview, you also interview a woman and you interview a person of color. There’s no excuse in this day and age to not do that.

I think we need to recognize that men are actually amazing, amazing allies in this battle.

This interview has been edited and condensed for clarity.