If you’re trying to reach your potential, when should you double down on your strengths and when should you mitigate weaknesses?

One view is that “if you work on your weaknesses you’ll end up with a lot of mediocre weaknesses.”

This is terrible policy. You can do fine in life if you are really good at math and just passable at English. Or exceptional at marketing and only mildly competent at finance. I can barely use Excel and it’s not destroying my life.

However, pushing in the complete opposite direction, to only focus on your strengths is equally naïve.

Take the talented programmer that has no social abilities, and so can’t move up in the company or build a client base. A basic ability to manage relationships and politics is a survival skill, not a nice-to-have. Or the tremendously charismatic sales guy that has no financial skills, and spends every dime he earns.

Clearly weaknesses can hold us back.

When your time is limited, how do you decide what strengths to maximize and what weakness to mitigate, in order to reach your potential?

Skills Multiply, not add

Start with the notion that skills are multiplicative, not additive.

Skill 1 x Skill 2 x Skill 3 = Ability.

This matters because if you have a complete zero in there anywhere, no amount of strengths will make up for it. If you’re completely brilliant but never do a minute of work, you get nothing. If you’re so shy that you can’t talk to someone without averting your eyes and blushing, it’s going to be almost impossible to compensate.

You have to start by looking at what the essential skills are in your field, and committing that you’re going to have to get at least to competent in them.

The good news is that any field can be reduced to about five or six fundamentals.

In Business, I’d say they are Sales/Marketing, Innovation, Operations, Finance and Management.

If you rank as a complete zero in any of these, it probably doesn’t matter how good you are at all the others — that one will hold you back. However, you only need to get to basic competence to be able to do it yourself when you’re first getting started, and then eventually to manage someone else doing it at a later stage.

Once you’ve established what the fundamentals are, there are two useful models for how to approach them.

The 80/20 vs. 10,000 hours.

The 80/20 approach to skill acquisition, as taught by authors like Tim Ferriss and Richard Koch is this: You can get 80% proficiency in a subject in about six to twelve months. Japanese, Tango, Marketing, anything.

The other approach is Anders Ericsson’s 10,000 hour rule, popularized by Malcolm Gladwell in his book Outliers. It states that the way to become world class at something is to apply ten thousand hours of deliberate practice.

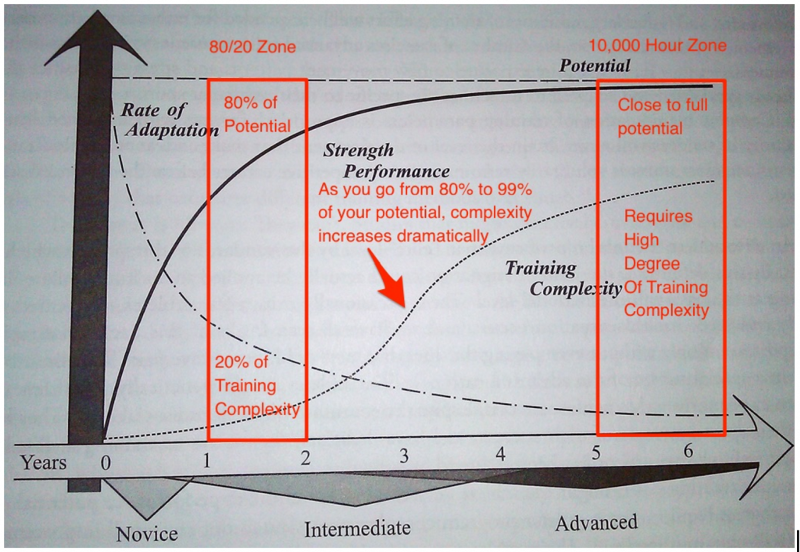

The phrase “don’t let the perfect be the enemy of the good” encapsulates the divergence between the two approaches. To go from 0% to 80% (good enough) requires a completely different approach than that needed to get from 80% to 99%. One approach is not better than other — rather, you’ll have apply both depending on what the situation calls for.

These two approaches can be understood by looking at research done in a field where the results are easily quantifiable: strength training.

According to Mark Rippetoe, author of the world’s most popular book on strength training, it usually takes twelve to twenty-four months of training to get to 80% of your genetic potential strength-wise. This can be done with only four exercises: squats, deadlifts, bench press and pull-ups. Do each of those exercises twice a week for three sets of five. Start with the bar. Each week, add five pounds.

With two to four hours a week, anyone can get to 80% of their genetic potential for strength within a year or two. That’s only 208–416 hours, tops.

To get from 80% to 99% of your potential, things get much more complicated and take much longer.

Anyone who is trying to go from 80% to 99% of their potential in strength sports, has sacrificed other aspects of life in pursuit of competitive success.

If you study guys at the top of their game, strength-wise, it is in most cases the defining activity of their life. Family going on a one-week vacation? Can’t go, missing a week of training could be a six-month setback.

No alcohol. Perfect sleep. All meals prepared in advance and weighed and measured for their macronutrient ratio.

They may spend two hours each day training instead of two hours each week. They spend hours each week just planning out their training trying to get the perfect combination of volume, intensity, and rest.

And they have been doing this day in and day out for five plus years. That’s a very different level of commitment to doing something for two to four hours per week for a year.

While this is most apparent in strength training, because you can precisely measure someone’s strength stats, it’s true in any field.

If you want to get to 80% of your potential as a writer, able to clearly communicate in email and the occasional article, that’s probably doable with a year of deliberate practice.

To get to 99%?

Stephen King spent “four to six hours a day, every day”

for a decade before he broke through as a successful commercial writer.

You can learn to play guitar in ten hours well enough to play most of your favorite pop songs. To become world class, it took The Beatles thousands of hours playing in crummy pubs in Germany.

So why not 80/20 everything and simply develop a portfolio of “good enough” skills?

All the gains accrue to people at the very top.

The gains disproportionately accrue to people at the top. The top salesperson in a team of ten will usually earn over half of the total commission. Stephen King probably sells more books than the rest of his category combined.

If you want to compete in the Olympics, being at 80% of your potential in ten different events won’t hack it. Olympic medalists are all at 99% of their potential for their chosen event. They are probably good enough at related events — a weightlifter might do some 80/20 sprinting and gymnastics in their training — but their overwhelming focus is on their core competency.

So you need to pick a very few things to tackle through the other framework: the 10,000 hour rule.

But how do you pick which of the essential ones to spend your 10,000 hours on? You apply The Calculus of Grit.

Researcher Angela Duckworth’s uses the notion of grit to describe how a person’s passion and perseverance in the face of difficulty are among the most important predictors of success. Grit is woven into the 10,000 hour rule. To log 10,000 hours of deliberate practice requires tremendous passion and perseverance.

The calculus is this: there’s a difference between what grit looks like to someone on the outside and what it feels like to you on the inside.

If you’re on the right path, then it should get easier over time for you relative to other people working on the same skill. Almost everyone that takes an introductory computer science course finds it difficult. If the third or fourth one is still excruciating, instead of exciting, and everyone is moving faster than you are with less work, it’s time to find a new field. Same with music. Or marketing. Or writing.

The great ones all put in the time, but they put time into things where they have a comparative advantage.

People often ask me how I read 60 books a year, and although I have some tips that I can share, a big part of it is that I find it much easier to read than most people. From the outside looking in, it seems like a lot of perseverance, but it’s easier to persevere when you feel yourself getting better more quickly than others.

I had the opposite experience of sales. I spent six months working full-time on sales and though I got better,I saw lots of other people around me getting better much faster than me. I’m glad I 80/20d my sales skills, but I’m not planning to log another 9,500 hours. I don’t have world-class sales potential.

What do people frequently ask you about that seems easy to you, but impressive to them?

That’s a good sign it’s worth investing more time into.

There’s a difference between skills and strengths

Scott Adams, creator of Dilbert, says that in order to be successful at something, you need to either be in the top 1% of a field, or in the top 25% of two or more different fields.

Here’s Adams:

The first strategy is difficult to the point of near impossibility. Few people will ever play in the NBA or make a platinum album. I don’t recommend anyone even try.

The second strategy is fairly easy. Everyone has at least a few areas in which they could be in the top 25% with some effort. In my case, I can draw better than most people, but I’m hardly an artist. And I’m not any funnier than the average standup comedian who never makes it big, but I’m funnier than most people. The magic is that few people can draw well and write jokes. It’s the combination of the two that makes what I do so rare. And when you add in my business background, suddenly I had a topic that few cartoonists could hope to understand without living it.

Capitalism rewards things that are both rare and valuable. You make yourself rare by combining two or more “pretty goods” until no one else has your mix…

It sounds like generic advice, but you’d be hard pressed to find any successful person who didn’t have about three skills in the top 25%.

This is outstanding advice. However, I would add one wrinkle to Scott’s advice: it’s important to distinguish between strengths and skills.

Skills are extrinsically defined. They are the way subjects were divided in school or how you describe yourself. They are things like physics, math, marketing, and programming.

Strengths are intrinsically defined. They are something you come to intuitively understand about yourself that has applications across a range of extrinsic skills.

You need to be in the top 25% of three extrinsic skills, but that combination is often you logging 10,000 hours towards an intrinsic strength.

For example, if you were to ask me what the three top 25% skills I’m developing are, I would tell you marketing, operations, and writing. This is true, but it sort of misses the point.

I’m not actually that good at marketing. I can think of people who are much better than I am at all the primary elements of marketing: pricing, positioning, product and place.

The success I’ve had with marketing is more a result of something that might be described as “contextualization.” I’m better than most marketers I know at understanding the context, and second and third order effects, of how new products are received. If a promotion goes out this week, it will affect customer behavior for years to come. Understanding how and why is one way to be effective at marketing, even though no one has ever taught contextualization as a part of marketing.

The same is true of writing. If I were to compare myself to other writers, I’m not particularly good at writing. I’ve got poor narrative skills and terrible grammar, but I’m better than most at contextualization in my writing. I write in an essay style because it lets me explore future consequences, which is my (relative) strength.

So my internal strength that I’m investing 10,000 hours into is contextualization.

In Scott Adams’ case, it might be something like “engaging, clear explanations.” If you read his book, it’s just as engaging, funny, and clearly articulated as his comics, even though it contains relatively few drawings. Removing one of his top three skills (drawing) from the book doesn’t make his strength any less effective.

Mitigating Weaknesses Can Mitigate Strengths.

If something is a weakness, you may want to 80/20 it, but not much more.

For starters, there’s the opportunity cost. If you have two machines and putting a dollar in one (mitigating weaknesses) gives you $1.10 back, but putting a dollar in the other (maximizing strengths) gives you $3 back, which machine would you put your money in?

Not only can it be a poor use of resources that could better be spent maxing out strengths, it can be outright harmful. According to LinkedIn Founder Reid Hoffman, “Most strengths have corresponding weaknesses. If you try to manage or mitigate a given weakness, you might also eliminate the corresponding strength.”

Reid is not particularly organized, but has done little to remedy it out of concern that focusing on getting organized will hurt his creativity.

“Creativity involves connecting disparate ideas. [Reid] is a non-stop generator of ideas — perhaps the unstructured tempo of his life is a positive enabling force. How intensely organized you are and how creative you are may be two opposite sides of the same coin.”

I have the worst rote memory of anyone I know. If I spend a lot of time with someone, they often get irritated because I will bring up the same topic over and over and have no recollection of having previously discussed it.

This used to really bother me until I read Einstein’s biography by Walter Isaacson. Einstein did exactly the same thing. He lost his keys and left his door unlocked all the time. He did it because he was always thinking about physics and not locking the door.

If he’d beaten himself up over not remembering to lock the door, he might not have discovered Relativity, but he would have saved on all the locks he had to have changed — a terrible tradeoff.

I do basic things to mitigate my problems. I write everything down and I implemented David Allen’s Getting Things Done system, which is enough to ensure that if I am collaborating on a project with someone, they can trust me to get done what I say I will get done.

Beyond that, I don’t worry about it too much. I probably pay a couple hundred dollars in “forgetfulness tax” every year from lost coats and the like, but it’s worth it. I get to spend more time thinking about things which, in the long run, are more valuable to me than a coat.

So it seems pretty clear at this point. Pick your domain, figure out the fundamentals, give them all a shot, see which is the easiest for you relative to other people, start investing your 10,000 hours on that, and 80/20 the rest.

How To Get Started To Reach Your Potential

I didn’t always know my strength was contextualization, because you can’t major in contextualization. There are no jobs for contextualization.

You have to pick one or a few skills and get started on them, and over time see what strengths emerge. Since you can find your strength and reach your potential through multiple domains, it doesn’t matter so much where you start, as long as you follow two heuristics.

The first heuristic is one we established earlier: always do more of what you find easy, that others find hard.

I worked in marketing for a few years, and it wasn’t until I moved to operations that I quickly realized that I wasn’t that great at marketing, I was good at seeing the full context and designing systems that consistently implemented basic block-and-tackle marketing.

When you are marketing yourself, it’s important to remember that most people won’t describe themselves by what their real strength is, because it doesn’t make sense to anyone but them.

I don’t walk around telling people I’m a contextualizer.

No one pays contextualizers. It’s not something that shows up in job ads. People pay marketers. People pay operations experts. People pay writers (although less than they pay marketers and ops guys).

However, when you make decisions about what to pursue, you want to be internally calibrated with your strengths. I choose projects where contextualization is a high leverage activity. That could be marketing, operations, or a totally different external field.

The second heuristic is: ship your work constantly.

The only way to know what your internal skill is, is to constantly release work and find the thread that runs through it, looking back. Ira Glass, the host of This American Life, had this to say:

“And if you are just starting out … the most important thing you can do is do a lot of work. Put yourself on a deadline so that every week you will finish one story. It is only by going through a volume of work that you will close that gap, and your work will be as good as your ambitions”

Acknowledgements: Ben Casnocha, Venkatesh Rao, Spencer Greenberg, Marc Andreesen,Scott Adams and Christina LoParco