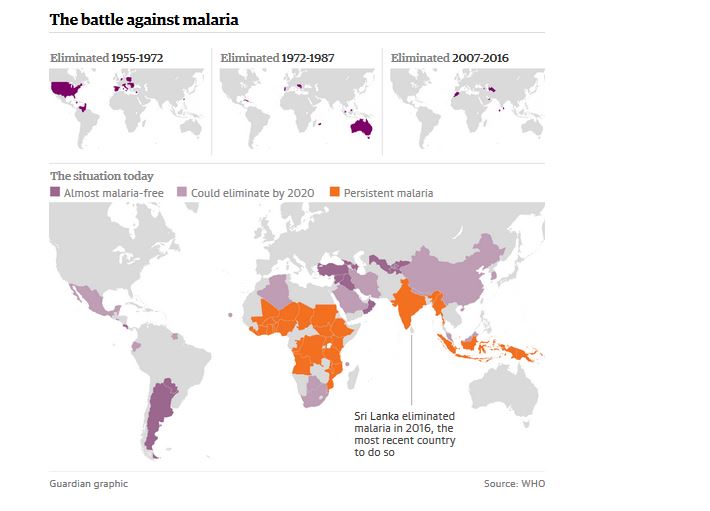

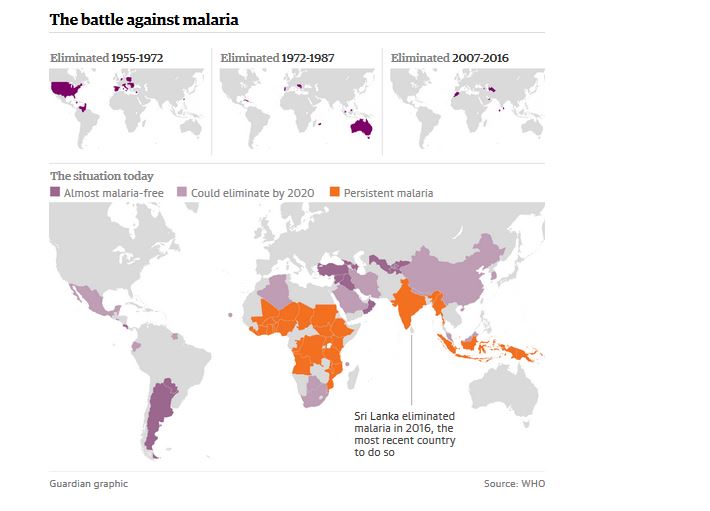

Hopes of eliminating malaria from more than 30 countries with a total population of 2 billion have risen following the successful removal of the disease from Sri Lanka.

Public health officials said 13 countries, including Argentina and Turkey, had reported no cases for at least a year and may well follow the success of Sri Lanka, which this week declared itself malaria-free after meeting the criterion of going three years without an infection.

By the end of the decade, another 21 countries, including China, Malaysia and Iran, could be free of the disease, which kills 400,000 people, mostly babies and pregnant women, every year.

Public health officials believe that in years to come the elimination from Sri Lanka, highly symbolic because the island came within a hair’s breadth of defeating malaria more than 50 years ago, may be regarded as the beginning of the end for the disease.

The director of the World Health Organisation’s global malaria programme said Sri Lanka had shown that, with commitment, any government could eliminate malaria, even with the tools available.

“The country took ownership of the problem themselves,” Dr Pedro Alonso said. “They wanted to eliminate malaria even in the face of the civil unrest they had in the last decade. They paid for it themselves.

“In a world where a lot of declarations are made, the translation of that commitment into real action is best exemplified by putting real resources in themselves,” he said. Other funders, such as the Global Fund to Fight Aids, TB and Malaria then came in with support.

Secondly, Sri Lanka had an enlightened public health system and academia. It did not just buy in millions of mosquito nets and drugs; it conceived a plan to solve its own particular problem.

Sri Lanka’s director general of health services said success came through teamwork and strong political commitment over many years.

“Elimination of malaria from every nation is possible. That’s the best lesson I guess: you have to work hard,” Dr Palitha Mahipala said.

More than 80% of Sri Lanka’s 22 million people live in rural areas which provide ideal ecosystems for Anopheles culicifacies mosquitoes, which are one of the main vectors for malaria in the region.

It was not possible to eliminate the mosquitoes from jungle areas, so the government focused instead on the parasite which causes the disease in humans, and is transmitted from person to person by the mosquito.

The quick diagnosis of malaria in children meant they could be treated earlier, reducing the chances of mosquitoes sucking up the parasites in their blood and transmitting the disease to other people.

Sri Lanka also sent mobile clinics into the worst-affected areas and spent time, money and effort on educating the public.

Other countries have also been doing well. The millennium development goals, set by the United Nations in 2000, focused minds and attracted money. The number of new malaria cases worldwide fell by 37% between 2000 and 2015 while death rates dropped by 60% overall and by 65% among children under the age of five.

The countries on the list of 21 that could eliminate malaria within the next four years, published by the WHO in April, are: China, Malaysia, South Korea, Iran, Saudi Arabia, Belize, Costa Rica, Ecuador, El Salvador, Mexico, Paraguay, Suriname, Bhutan, Nepal, Timor-Leste, Algeria, Botswana, Cape Verde, Comoros, South Africa and Swaziland. All have brought down malaria cases dramatically and share a political commitment to the endgame.

Last year, the UN and the Bill and Melinda Gates Foundation devised a plan to eradicate malaria worldwide by 2040. It was not an outrageous suggestion; for the past 15 years, there have been ever more ambitious and hopeful strategies and statements from global organisations and leaders on the prospects of ending malaria.

But there are stubborn spots. The countries where the problem is most difficult to tackle are still in sub-Saharan Africa, which is suffering most of the child deaths.

“There should be no deaths in malaria if you have the right health system and identify patients early on,” Alonso said.

The Democratic Republic of the Congo and Nigeria suffer more than 40% of all malaria deaths. Tanzania, Uganda, Mozambique and Côte d’Ivoire also have heavy burdens of disease.

With resistance building to the best available drug, artemisinin, and the first-ever vaccine providing only low-level protection, new tools are needed, but most important is the sort of determination shown by Sri Lanka’s government.

“Eradication is the only sustainable solution to malaria,” Bill Gates said on the release of the report his foundation produced with the UN last September. “The alternative would be endless investment in the development of new drugs and insecticides just to stay one step ahead of resistance. The world can’t afford that approach.”

The reason why Sri Lanka’s success is so symbolic is because we have been here before. In 1955, the UN committed to ending the scourge of malaria. It was optimistic because it thought there were effective tools. The pesticide DDT had been found to kill the mosquitoes that were spreading the disease in US army camps in the Pacific during the second world war. Widespread use of DDT and the drug chloroquine drove malaria out of many countries in the Americas, Europe and parts of Asia.

But it all fell apart. There was no real attempt to tackle malaria in sub-Saharan Africa because it was thought to be too difficult. Elsewhere, elimination fell foul of the problem that has bedevilled all malaria control efforts: resistance of the malaria parasite to drugs and of the mosquitoes to pesticides. Then in 1962, Rachel Carson’s blockbuster Silent Spring was published, alerting the world to the environmental devastation wreaked by DDT. The UN’s malaria eradication plan was officially scrapped in 1969.

Sri Lanka had been so close. Two million cases a year had dropped to just 17 in 1963. But when control efforts ended, the numbers surged back up and malaria was endemic once more. By 1998, there were more than 250,000 cases a year.

“In the world of malaria, Sri Lanka carries a special weight,” Alonso said. “It is often cited as the example of what happened during the first malaria eradication programme. They didn’t complete the job and malaria came back with a vengeance. We need to learn from the past so we don’t repeat the mistakes.”

Elimination means the end of malaria in a country or region. The aspirational talk is of eradication: “making the parasite disappear from the face of the planet”, Alonso said.

Realistically, he said, the tools, knowledge or physical resources were not available to do that. But as one country after another succeeded in eliminating malaria, it was possible they would obtain all of those things and be on track to end the disease.

Eradication has been achieved in only one disease so far: smallpox. The eradication of polio is so close and yet so far, with small numbers of cases in just a few countries but also a constant sliding back, as seen recently in Nigeria, which had been considered polio-free.

Additional reporting by Dinitha Rathnayake