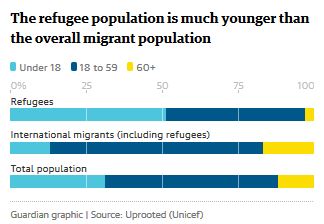

Children now make up more than half of the world’s refugees, according to a Unicef report, despite the fact they account for less than a third of the global population.

Just two countries – Syria and Afghanistan – comprise half of all child refugees under protection by the United Nations High Commissioner for Refugees (UNHCR), while roughly three-quarters of the world’s child refugees come from just 10 countries.

New and on-going global conflicts over the last five years have forced the number of child refugees to jump by 75% to 8 million, the report warns, putting these children at high risk of human smuggling, trafficking and other forms of abuse.

The Unicef report (pdf) – which pulls together the latest global data regarding migration and analyses the effect it has on children – shows that globally some 50 million children have either migrated to another country or been forcibly displaced internally; of these, 28 million have been forced to flee by conflict. It also calls on the international community for urgent action to protect child migrants; end detention for children seeking refugee status or migrating; keep families together; and provide much-needed education and health services for children migrants.

“Though many communities and people around the world have welcomed refugee and migrant children, xenophobia, discrimination, and exclusion pose serious threats to their lives and futures,” said Unicef’s executive director, Anthony Lake.

“But if young refugees are accepted and protected today, if they have the chance to learn and grow, and to develop their potential, they can be a source of stability and economic progress.”

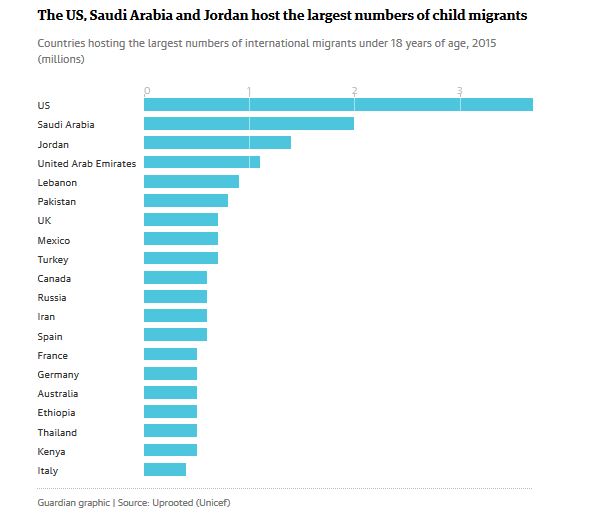

Today children comprise one-eighth of all international migrants in the world (31 million children out of 244 million total migrants), according to 2015 data. The vast majority of child migrants – some 3.7 million children – live in the US, followed by Saudi Arabia and Jordan, while in Europe, the UK hosts the largest number of migrants under the age of 18 (close to 750,000).

Unicef UK is calling on the UK government to step up action to ensure that refugee children stranded in Europe can reach safety with their families in the UK.

“Today, nearly one in every 200 children in the world is a refugee,” said Lily Caprani, Unicef UK’s deputy executive director. “In the last few years we have seen huge numbers of children being forced to flee their homes, and take dangerous, desperate journeys, often on their own. Children on the move are at risk of the worst forms of abuse and harm and can easily fall victim to traffickers and other criminals.

“Many of these children wouldn’t resort to such extreme measures if the UK government made them aware that they may have a legal right to come to the UK safely, and if they provided the resources to make that process happen before these terrible journeys begin.”

The vast majority of the world’s child migrants live in Asia or Africa, the report says. Asia is the birthplace of nearly half (43%) of all the migrants in the world, with nearly 60% of these migrants moving within the region. Most of Asia’s child migrants are hosted in Saudi Arabia, which also receives the highest number of labour migrants – the report’s authors say more research is needed to understand the connection between the two.

Globally, Turkey has the largest share of refugees – including adults – under protection by the UNHCR, and is believed to host the most child refugees as well.

In Africa, nearly one in three migrants is a child – nearly twice the global average – and three in five refugees are children. African migrants move both within and beyond the continent’s borders in nearly equal numbers; South Africa and Ivory Coast are the top two host countries for immigrants. But on-going conflict in many countries, in addition to linguistic difficulties between peoples and extremely limited resources to deal with migrant and refugee populations, mean that “the economic and social pressures of hosting threaten to uproot refugees once more”, the report warns.

Understanding how and why children move within or beyond their birth countries is hugely important but usually hidden from view, says Dale Rutstein of Unicef’s Office of Research – Innocenti, which is investigating the multiple drivers that push children to start new lives, and the problems that they face as a result.

“The systems we have in place for people fleeing or seeking asylum are focused on adults, and in no way are articulated for children,” he says. “They are usually based on border control and law enforcement, yet we know that detention for a child is the worst thing that can happen and can create significant problems [for] a child’s development. But time and time again, we see that states don’t have any system for [holding] children apart from [putting them in] detention.”

Data clearly shows that refugee and migrant children disproportionately face poverty and exclusion despite being in great need of aid and resources, and in many circumstances are required to handle their own legal cases as they lack any form of legal representation.

“In many parts of the world, children are often and regularly in court proceedings where they have no legal representative and no adult representation, most notably on the border between Central America and the US,” says Rutstein.

“Think of how absurd it is for a child to be arguing their case against a government-appointed lawyer. Often states believe they are set up to protect ‘their own’ children, but children have to be children anywhere and everywhere, and need to have the same standard forms of protection and treatment [around the world].”

The report calls on the international community to fulfil the Convention on the Rights of the Child, the most widely ratified human rights treaty in history, which obliges ratifying countries to respect and protect the rights of all children within their territories, regardless of a child’s background or migration status. While legal frameworks protecting refugees and other adult migrants is unclear and fragmented, the report says, the children’s convention is clear and unequivocal, taking into account minors’ particular vulnerabilities.

![Of Burundi's more than 250,000 refugees, most are young women and children [Dai Kurokawa/EPA]](https://abovewhispers.com/wp-content/uploads/2016/09/Burundi-Refugees.jpg)