At the Softex refugee camp in northern Greece, it is lighter by night than it is by day. Inside this windowless former warehouse, the lamps only work in the evenings. That is partly because the place was not designed to house people. It is part of what was a toilet paper factory.

“It’s insulting,” says Hendiya Asseni, a 62-year-old Syrian, of being housed in a one-time loo-roll store. “But then everything here is insulting – the life, the food, the fact we have a toilet in front of our tent.”

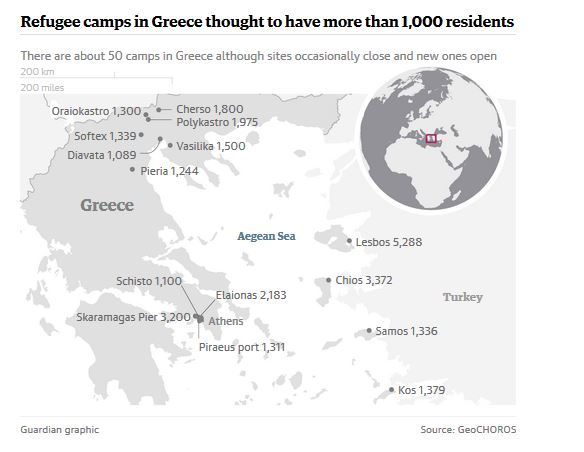

This humiliation is the logical conclusion of the migration policies that Europe has pursued since the death of Alan Kurdi this time last year. Attempting to stem the flow into Europe, politicians have established a deportation deal with Turkey, from where most Europe-bound migrants depart, and built fences throughout the Balkans, trapping about 50,000 people in Greece.

Some still smuggle themselves north. But the vast majority of those still on Greek territory when the borders shut in March are now stranded in about 50 squalid camps across the country. At least seven were infested with snakes and scorpions, aid workers said. In another, the mattresses were full of bed-bugs. But the most notorious is Softex.

“How symbolic is it that of all the empty buildings, of all the places for a refugee camp, one of the biggest and most permanent has been set up in a disused toilet paper factory?” asks Nico Stevens, head of projects for Help Refugees, a British charity funding improvements at the camp. “It’s very emblematic of the situation as a whole.”

Softex sits in an industrial wasteland on the northern fringes of Thessaloniki, Greece’s second city. Refugees have been here since the border shut in May, forcing the cash-strapped Greek authorities to hastily house people in whatever spaces they could find. Several hundred have now smuggled their way north, but about a thousand are still left. Most of them live in tents inside the gloomy warehouse. The rest sleep outside, a few hundred metres from a grim row of burnt-out trains and factory chimneys.

“We’re suffering, emotionally – we’re not good,” says Mohammad Mohammad, a 30-year-old taxi driver whose wife and children are under siege in a Damascus suburb. Mohammad came to Greece in February, hoping he could make his way to Germany, claim asylum, and then apply for his family to join him. Instead, the border shut before he could leave – meaning that he must pay a smuggler to take him north, or wait for the EU relocation programme to assign him a permanent place elsewhere in Europe.

But as so many stuck in Greece point out, relocation is not working properly – with just 5,100 places made available in the space of nearly 12 months. “The system doesn’t work,” says Mohammad. “At this rate, they’ll need 10 years to get it finished. But if we’re here for another month, we’ll be in a mental asylum.”

It is a familiar sentiment. Interviewees consistently said that the limbo they are trapped in – which has left them far from loved ones, without access to work and education, and without any clarity on their future – has led to a wave of depression and mental health problems.

Abouni, 17, is at Softex without his parents and sister, who are still under siege in Aleppo. As a minor, Abouni hoped to apply for family reunification after being granted asylum. Instead he is likely to turn 18 before that can happen, and he says the anxiety of the situation has led to him being taken to hospital four times with panic attacks.

“Sometimes I feel so angry that I can’t breathe, and then I fall unconscious,” says Abouni, who asked to be referred to by a pseudonym to avoid being stigmatised at the camp. “I have family in Syria under the bombs, and when I talk to my little sister on the phone, she asks if she’ll ever see me again. I’m stuck here in this jail.”

At the Vasilika camp outside Thessaloniki, one of seven visited recently by the Guardian, the warehouse is brighter than at Softex but the despair is the same. Hisham worked as a medic for an international aid group for 10 years in Syria but now finds himself as its beneficiary rather than its employee. The work he did in Syria still haunts him, with the images of dead bodies flashing before him as he tries to sleep at night.

“For years I saw people getting killed in Syria, and then you’re here for six months without knowing what’s going on, and I cannot sleep,” says Hisham. “What happened in Syria is playing every night like a film in front of my eyes. Psychologically, I need a doctor.”

Even basic health services are hard to come by. Aid groups like the Red Cross are present during working hours at most camps, but the services they can provide are limited. In serious cases, ambulances sometimes take too long to arrive. At Softex, Hendiya Asseni’s husband, a 71-year-old former civil servant, had his fifth stroke. Asseni said the ambulance took more than an hour to arrive. When he finally reached hospital, the doctors said he was too weak to live in a tent. But their advice was ignored, and he was still taken back to the camp a few days later.

Medicine is also scarce. At Vasilika camp, Mohammad Ibrahim, 10, has a blood disorder known as thalassaemia, a condition his sisters died from. The Greek government pays for Mohammad’s blood to be transfused once a month, but they cannot supply the medicine he needs. His existing supply, his brother Rezan says, “will run out in about two weeks. And the hospital says they don’t have any more.”

To add to all this, no one feels safe. The camps are nominally run by the army and patrolled by the police. But officers usually leave at night, and by day their presence is often light. Like in any population of 50,000 people, this has allowed a small minority of refugees in some camps to form gangs. According to testimonies from both refugees and aid workers, these gangs have sometimes robbed and attacked other asylum seekers, abused women, and forced others into prostitution.

Maria Diakopoulou helps run a programme that moves some of the camps’ most vulnerable residents into private accommodation in Thessaloniki. One woman Diakopoulou helped “was taken by the leader of the mafia in the camp, badly beaten, and was then made to have sex with people in the camp. The [gang leader] took the money.”

The Guardian is aware of other alleged cases of sexual abuse, including ones committed by non-refugees, but has agreed not to publish details in order to preserve the anonymity of the victims. More generally, the issue is “of serious concern” to the UN refugee agency.

“We are extremely worried about it,” says Roland Schoenbauer, a senior UNHCR spokesman in Greece. “It’s closely linked to substandard living conditions for asylum seekers in Greece. In many places, there are no gender-segregated toilets, there are showers without doors, and there are sleeping areas where [both genders] are together.”

In some cases, asylum seekers have willingly entered the sex trade because they feel they have no other choice.

On a recent night in Athens, Hassan describes how he knows when a man wants to pay him for sex. “With experience you can tell from someone’s stare,” says Hassan, a pseudonym. “Or when you’re sitting on a bench, and someone sits down next to you.”

Originally an estate agent, Hassan did not want to discover all this. Nor did the dozens of other Iranian and Afghans who have turned to prostitution in Athens in recent months. “But we’re stuck here in Greece and we have no other way of making money,” says Hassan, a 29-year-old Iranian. “So we’re forced to do this.”

Men have long sold sex in the Pedion Areos park in central Athens, but those familiar with the scene say their numbers have spiked in recent months – once Europe began tightening its borders over the winter.

Photograph: Patrick Kingsley for the Guardian

Ahmed Sher, a 36-year-old Afghan, has been working in the park on and off for several years – and now reckons he has around 30 to 40 new competitors. “I’m making a lot less money, and I have less work because there’s so many more people in the park,” he says, in a cafe near the park entrance. “Since the border closed, every 10 or 20 minutes you can see a young guy going inside the [undergrowth] with an older guy.”

Hassan reached Greece from Iran in February, aiming to join the thousands of other asylum seekers heading north through Macedonia at the time.

But by that point the Macedonian border closed to Iranians – and later to all nationalities – so Hassan tried six times to get smuggled through the Balkans instead. Each time Hassan was caught, he says, “and my smuggler ate all my money”. He had no means of moving on – and no means of staying put. Then a friend told him about the park.

“Most of us come as a joke,” says Hassan. “We hear about it and we think we’ll see what it’s like. But then when our families stop sending us money, we have to come here full-time.”

Perhaps the greatest desperation can be found on the islands, where you can find the most overcrowded camps. Before the deportation deal with Turkey began, new arrivals could move quickly to the mainland. But since March, most newcomers have not been able to leave legally – while deportations have largely failed to materialise. So the camps are overflowing, leading to tensions with some local residents. On the tiny island of Leros, refugee campaigners were told to leave by a mob of angry islanders, while on Chios, a dead rabbit was left outside an activists’ kitchen.

Refugees there face an even more precarious fate. Many are “very depressed”, said Methkal Khalawi, a Syrian oil technician stuck on Chios. “I see a lot of them crying deeply. They are here in exile, nothing more. Prisoners of Europe.”

Here and there, there are small signs of improvement. The camps are gradually being refurbished, often thanks to volunteer groups. The Greek government will attempt to place all refugee children in some kind of education this autumn. UNHCR hopes to move 10,000 people out of the camps, and into private accommodation. Small private projects – like Maria Diakopoulou’s – are also helping to integrate refugees into local households and communities. About a fifth of the 100 refugees in her scheme now have some kind of work, and some have set up an informal business.

But most observers acknowledge the general situation is dire – and has the potential to turn into a long-term tragedy.

The EU relocation scheme and the EU-Turkey deal are collectively meant to see most asylum seekers moved out of Greece. But with both schemes faltering, one of the early architects of the EU-Turkey deal believes many refugees may end up never leaving.

According to Gerald Knaus, the thinktank chief who first envisaged the deal last September, Greece could end up becoming a giant holding pen for refugees, performing the same controversial role for Europe that Nauru and Manus Island perform for Australia in the Pacific.

If the situation does not improve, Knaus says, “then what we have instead is an Australian-style system, where Greece becomes Nauru.”

Additional reporting: Mohammad Ajouz and Leila Moghaddam