.

Photograph: Muyingo Siraj

I first met Phiona Mutesi in September 2010 sitting on the mud stoop of her family’s shack in one of the most challenging places on earth: Uganda’s Katwe slum. I had been told about Phiona; how at the age of nine she could neither read nor write and had dropped out of school, when she met a Ugandan missionary, Robert Katende, who offered to teach her the game of chess – a sport so foreign in Uganda that there is no word for it in Phiona’s native language – and how in just four years she had become an international chess champion. On that autumn day, Phiona’s mother Harriet looked as defeated as any person I’ve known. She had been forced to relocate Phiona and her two brothers five times in the previous four years, once because they’d been robbed of all their meagre possessions and another time because Harriet feared their house was about to collapse.

Phiona’s latest home consisted of one 10ft x 10ft room with no windows and a tin roof so dilapidated that every rainstorm flooded the shack. The house contained little more than a wash pot, a tiny charcoal stove, a teapot, a worn toothbrush, a cracked mirror, a Bible and two musty mattresses for the entire family to sleep on.

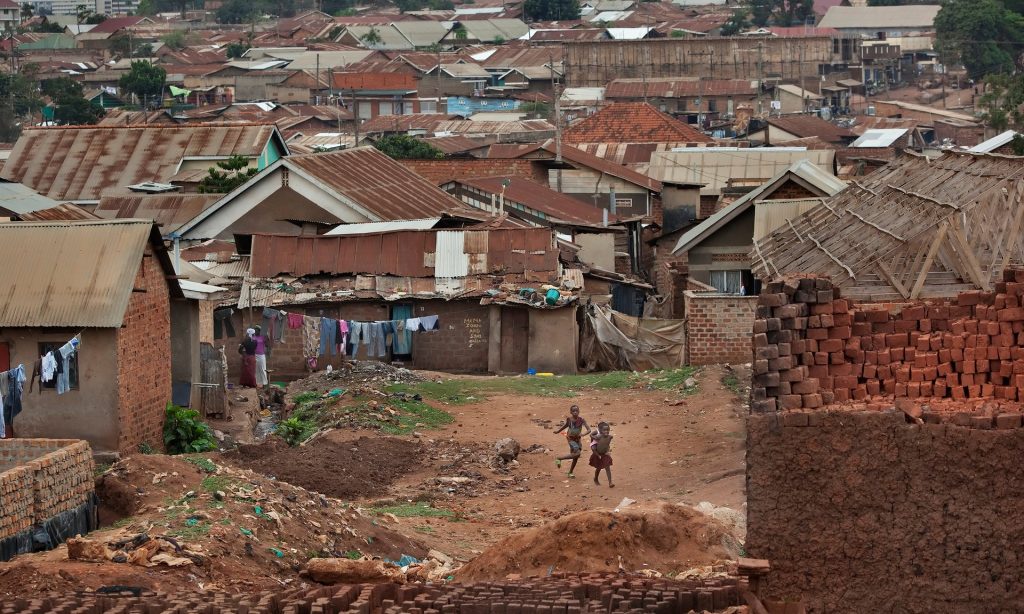

Katwe (pronounced kah-tway), in the south of Uganda’s sprawling, smoggy capital city of Kampala, emerged in the mid-20th century as a place for poor artisans, but developed into the city’s most crime-ridden slum. It has scant sanitation and during the rainy season is regularly flooded with raw sewage, with residents sleeping on their roofs to avoid drowning. If you are born in Katwe, the chances are you will die in Katwe. It’s estimated that 40% of teenage women in Katwe have children. “I call it a poverty chain,” Katende told me. “The single mother cannot sustain the home. Her children go to the street and have more kids and they don’t have the capacity to care for those kids. It is a cycle of misery that is almost impossible to break.”

Photograph: Stephanie Sinclair

During our initial meeting, Phiona didn’t speak comfortably because she had never been encouraged to share her thoughts. She began by telling me she had no idea when she was born because birthdays aren’t something people keep track of in Katwe. (Harriet guesses her daughter was born in 1996.) I asked her about her earliest memory. “I remember I went to my dad’s village when I was about three years old to see him when he was very sick, and a week later he died of Aids,” she said. “After the funeral we stayed in the village for a few weeks and one morning when I woke up my older sister Julia told me she was feeling a headache. We got some local herbs and gave them to her and then she went to sleep. The following morning we found her dead in her bed. That’s what I remember.”

Harriet recalls that when Phiona was a child she nearly died twice of illnesses that were never diagnosed, but probably related to malaria. Phiona dropped out of school shortly after her father died and she began selling boiled maize from a saucepan on her head. One afternoon in 2005 she secretly followed her older brother Brian in the hope that he might lead her towards a meal. She hid and watched him enter a dusty veranda to play with some black and white pieces. The young girl had never seen anything like these figures. She thought they were beautiful. “When I first saw chess, I thought, ‘What could make all these kids so silent?’” Phiona said. “Then I watched them play the game and get happy and excited, and I wanted a chance to be that happy.”

She dared to peek into the veranda again, fascinated by this new game and also curious if there might be any food inside. This time Katende spotted her. “Young girl,” said the coach. “Come in. Don’t be afraid.”

Robert Katende also has no idea when he was born, only that he was an illegitimate child whose mother gave birth to him when she was a secondary-school student. He was transferred to his grandmother’s care, and it wasn’t until Katende was four years old and reunited with his mother in Kampala’s Nakulabye slum that he learned his name was Robert. His mother died when he was around eight and he embarked on an odyssey of despair. Because of civil war in Uganda, he lived much of his childhood on the run, scrounging for food and sleeping hidden in the bush. He would become another slum kid sustained by sport.

Katende had grown up playing football barefoot and by the time he reached secondary school he displayed such wondrous talent as a striker that he took requests from friends to score goals. One day he leapt for a header, crashed into the opposing goalkeeper and the resulting fall nearly killed him.

Photograph: Xan Rice

Though doctors told him he would never play football again, he was back juggling a ball within months and eventually joined a Christian football club that ministered to youth in the slums. Katende had found his calling.

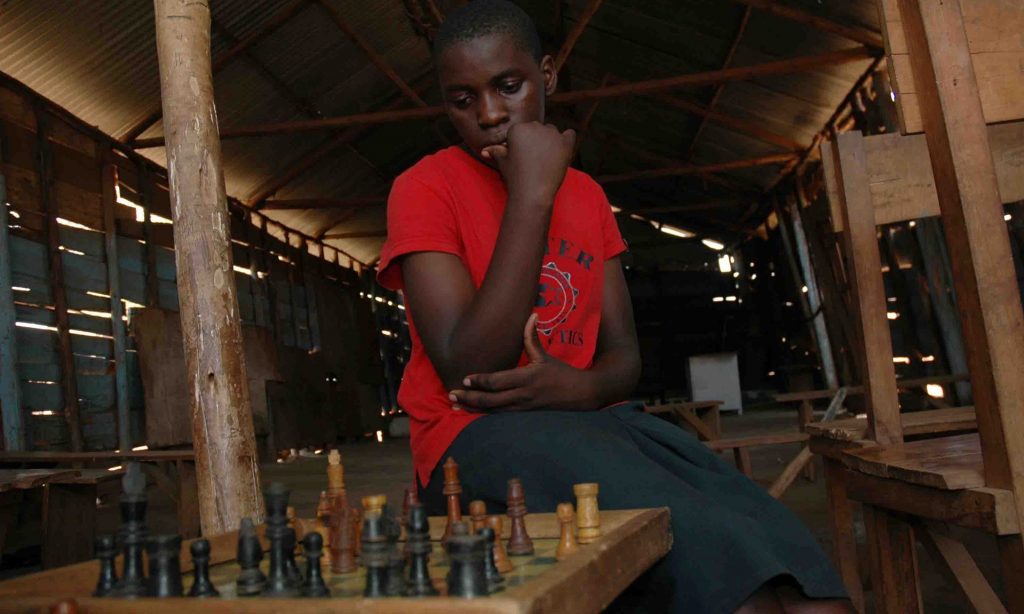

He was assigned to Katwe and for a year he brought football and a little food to the children of the slum, until he realised some of the children had no desire to play football. He tried to figure out an alternative activity and eventually settled on chess, a game he’d learned to play as a student. “I had my doubts about chess in Katwe,” Katende said. “With their status and their background, I wondered, ‘Can these kids really play this game?’”

What gave Katende hope was that chess is a test of survival through aggression, an idea with which every slum kid could identify. Katende’s Katwe chess project began with just six students, who would become known as the Pioneers.

Soon, Phiona’s brother Brian joined them and a year later a barefoot girl in a muddy skirt peeked into the veranda and caught Katende’s eye. Phiona’s first chess tutor was Gloria, a four-year-old girl who knew little more than the names of the pieces and how they moved. Within a year of learning the game, mostly through trial and error, it became evident that Phiona had a special gift for the sport. “Chess is a lot like my life,” she said. “If you make smart moves you can stay away from danger, but any bad decision could be your last.”

Every day Phiona walked six kilometres to play chess. During her earliest games, she played recklessly, sacrificing critical pieces in an attempt to defeat her opponents as quickly as she could. Said Phiona: “I must have lost my first 50 matches before Coach Robert persuaded me to play with calm and patience.”

Katende began teaching her everything he knew about the strategy of the game and by the age of 11 Phiona was Uganda’s junior girls champion. Her confidence rose. “Her personality with the outside world is still quite reserved because she feels inferior due to her background,” Katende said. “But in chess I am always reminding her that anyone can lift a piece because it is so light. What separates you is where you choose to put it down. Chess is the one thing in Phiona’s life she can control. Chess is her one chance to feel superior.”

In 2009, Phiona and two boys from Katende’s Katwe chess project represented Uganda in Africa’s International Children’s Chess Tournament in Sudan. It was one of the first times Phiona had ever left Katwe. It was also her first flight and when her plane ascended through a cloud bank into the sun and blue sky, Phiona turned to the Ugandan chess official seated beside her and asked, “Is this heaven?”

In Sudan, Phiona enjoyed her first stay in a hotel. It was the first time she had slept in her own bed and used a flush toilet and ordered a meal from a menu, an odd notion for someone who had never before been granted a choice of what to eat. “I could never have imagined this world I was visiting,” Phiona said. “I felt like a queen.”

The Ugandan trio of slum kids, by far the youngest competitors in the tournament, defeated far more experienced teams from 16 other African nations to win the championship. When they returned to Katwe, they were greeted as conquering heroes. They discussed who might keep the trophy and concluded that none of them could because it would certainly be stolen.

They also fielded some odd questions: did you stay indoors or in the bush? Why did you come back here? As Phiona left the celebration that evening, someone excitedly asked her, “What is the first thing you’re going to say to your mother?”

“I need to ask her,” Phiona said, “‘Do we have enough food for breakfast?’”

After a few days of getting to know her in September 2010, I flew to Russia with Phiona and Robert for the Chess Olympiad, the world’s most elite team chess event, being staged that year in Khanty-Mansiysk, Siberia. Once again this proved to be a learning experience. Phiona turned on the water for her first ever shower and quickly jumped out. She asked her roommate why anybody would want to use such a thing and then she was informed that there was a handle for hot water as well. One of the youngest players at the tournament, Phiona earned a win and a draw for the Ugandan team in her seven matches.

But Katende’s enduring memory was after Phiona’s third match when she was soundly defeated by an Egyptian grandmaster and she promptly marched over to her mentor and told him, “Coach, I will be a grandmaster some day.”

“That will take a lot of work and perseverance,” Katende told her. Phiona savoured the meals at her hotel’s all-you-can-eat buffet and left Russia stating that returning to Katwe felt like going to jail. It was a trip both triumphant and sobering.

Two years later, Phiona performed well enough in the 2012 Chess Olympiad in Istanbul to become Uganda’s first woman ever to earn a chess title, Woman Candidate Master, the first step on the ladder toward grandmaster. Then she made her first trip to the United States to help promote our book, The Queen of Katwe.

It was during that visit that I first recognised Phiona’s power to inspire. She came to my son’s third grade classroom and a bunch of restless nine-year-olds fell silent as she shared her story. Only two of the 20 students in the class knew how to play chess, so Phiona sat down at one of the tiny school desks and began patiently teaching the game the way Gloria had once taught her. The next day the students begged to play chess again. The following year the entire third grade competed in chess and the year after that more than 200 kids in four grade levels were all part of what had become known around school as the Phiona Mutesi Chess Club.

I travelled back to Uganda in July and was greeted at the airport by Madina Nalwanga, the teenager who plays Phiona in the upcoming Disney movie, Queen of Katwe. Nalwanga is another child of the Kampala slums. “Phiona’s story is inspiring young girls like me all over Uganda,” Nalwanga told me. “We now believe that we too can reach big dreams.”

A few days later, I had lunch with the real Phiona. She is now 20 years old and it is remarkable how much she has matured in the six years since I first met her on the stoop of that one-room shack in Katwe. She is still unfailingly humble, unaffected by the publicity swirling around her as the film prepares to premiere in cinemas around the world this autumn. Phiona is a confident young woman, who speaks English fluently. She is in the final year of secondary school at a boarding school in Katwe. She spends holidays at her mother’s newly constructed house in a lush valley several kilometres outside Kampala. Phiona and her family are finally financially secure based on earnings from the book and movie contracts. She told me she is considering going to Harvard university next autumn.

Phiona still dreams of becoming a grandmaster in chess, though she has hit a ceiling in Uganda because there is no coach qualified to train her to a higher level, a barrier that could be erased if she decides to study in the United States.

I asked Phiona if she’d seen the movie. “No, I haven’t watched it yet,” she told me, flashing her charming gap-toothed grin. “I already know the story.”

It’s true that The Queen of Katwe – book and movie – may be complete, but the Queen of Katwe’s story is really just beginning and it will be fascinating to watch her next move.

The Queen of Katwe by Tim Crothers is published by Abacus, £8.99. The film is released at the end of September