n the first day of her new job, Meera* came home after dark, and the elders of her household scolded her. “What kind of job is this that means you have to stay out so late?” they shouted. “You can’t do this work – tell them you won’t be coming back tomorrow. What will the other villagers say if they hear that you are out on your own at this time?”

Meera was a student in her second year of university. The job was being a reporter on a new local newspaper, and she had taken it to fund her education.

On her first day, she and another reporter, Kavita*, had done interviews in a village 70km away, and night had fallen before they returned.

“I couldn’t speak back then, the way I’m speaking to you now,” says Meera. “I was quiet, used to doing what I was told. Kavita was the one who spoke to my family, and convinced them to let me keep working.”

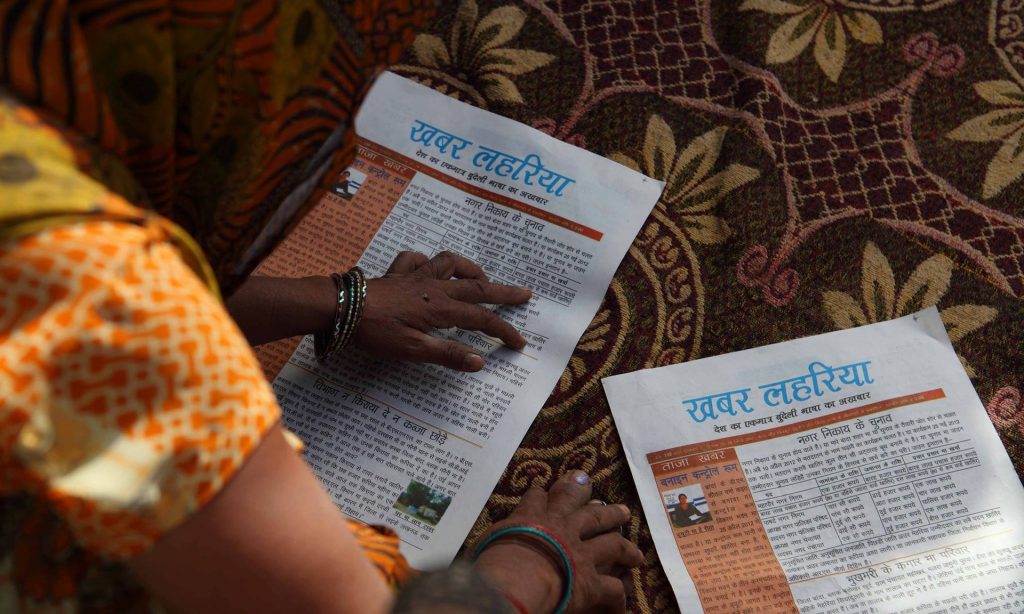

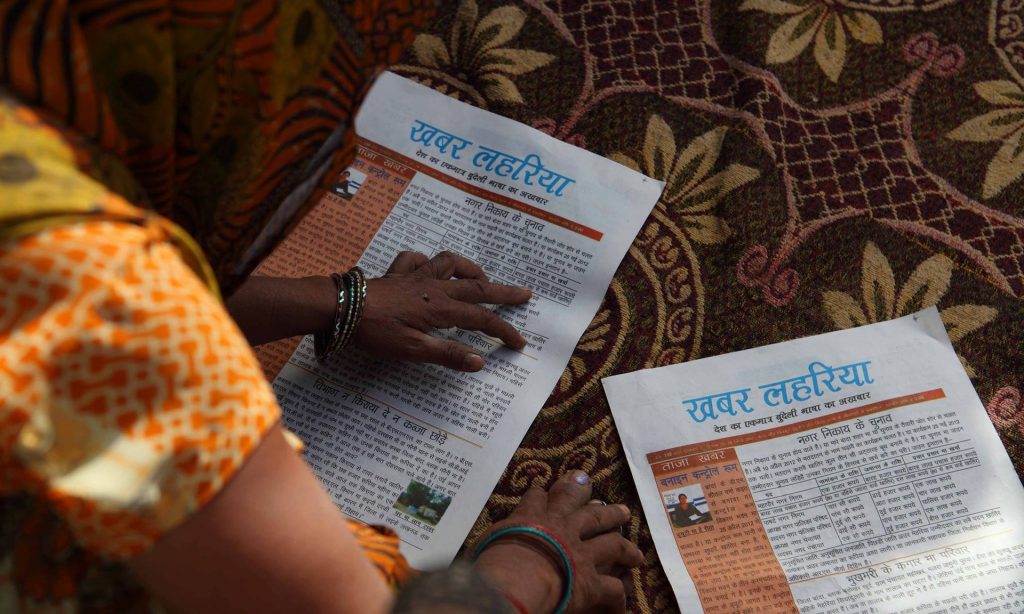

Fourteen years on, Meera is chief reporter at the same newspaper, Khabar Lahariya (News Waves). The newspaper is the first and only paper in India staffed, edited and run entirely by women, mostly from low-caste, rural backgrounds.

The paper covers local and rural issues in Uttar Pradesh, Madhya Pradesh and Bihar, Indian states with strong patriarchal attitudes to women’s rights. When Meera started, the paper was printed fortnightly, and hand-delivered by the reporters who were out in the villages gathering stories. Now, it is making its first forays in digital publishing and trying to make money through advertising, rather than relying on donations from NGOs.

As smartphones and internet use increase in India’s villages, Khabar Lahariya has adopted a digital-first strategy. Reporters are filing video reports, and instant updates on WhatsApp and Facebook, to reach new audiences. They have been trained and given smartphones so they can film, take pictures and send updates on developing stories instantly. Between April and June, the website received more than 700,000 hits, while the now-weekly print paper has a loyal readership of more than 50,000.

“Using video has increased our prestige,” says Meera. “It is easy to work with, and it shows people that we are on the ground and reporting facts, that we’re not just making things up. The only thing is, when something big happens and other news crews from the big channels are there too, people always want to be interviewed on the big cameras first. I tell them that our little phones are doing the same job as those big cameras.”

Over the past decade, a digital revolution has swept across India, and more than 350 million Indians have access to the internet, most of them on smartphones. In rural India, millions of people still live without electricity, but most households have at least one solar-powered battery charger for their mobile phone. Without television, or easy access to urban centres, smartphones are often the only source of entertainment. “People in rural India are looking for news that’s local, and there’s no one else apart from Khabar Lahariya that’s really giving that to them,” says Suhas Mishra, a businessman who has invested in the paper.

“Every house has at least one smartphone now,” says Lakshmi Sharma, a video producer in the newspaper’s head office in Delhi. “Even if you don’t buy anything else, you’ll make sure you have enough balance on your phone to use the internet.” Sharma gets alerts on her phone as reporters from around central India send her videos they have shot on their smartphones. Her job is to commission ideas, edit videos for the website, add voiceovers and keep tabs on reporters in the field.

Like most of the women who work for Khabar Lahariya, Sharma never thought she’d become a journalist. “I come from a village where women still live behind the purdah,” she says, referring to the tradition of keeping women secluded. “When I started working, it was the first time I had ever left my house alone. By the time I took my year eight exams I was already married, and by the time I was 15 I had my first child. But I couldn’t just sit at home and do housework all day.”

Sharma was the first in her family to get a smartphone, a gift from her husband, who wanted to support her work. “I’ve always liked technical things, and I’m the person in our house who knows the most about phones and technology,” she says. “People are impressed by how much I know.”

Though smartphones have made reaching people easier than ever, connectivity in villages is still a major problem. “I get calls from reporters saying they have been filming reports for two or three days, and they just can’t get a 3G signal to send them,” says Kavita, now the digital head. “Some of them have to travel 20 or 35km by bus and on foot just to get a connection to send them.”

Shalini Joshi, who co-founded Khabar Lahariya, said that when she set up the paper there were very few women in journalism in rural India, and very few newspapers that were independent. “By independent I mean not influenced by corporate or political agendas. I saw a gap in rural Uttar Pradesh and that region, and I wanted to bring more women into journalism and establish an independent newspaper.”

She says the paper aims to tell stories from a feminist perspective. “We try to give women voices, and tell stories from their points of view when possible. We have a whole page dedicated to women’s issues in the paper and a women’s column on the website.”

In rural India, women are still expected to work at home. Reporting news and discussing politics is seen as men’s work, and many women on the Khabar Lahariya staff have faced threats and danger while working. “Many women are intimidated and ridiculed for doing their jobs. We have one reporter who was threatened so seriously by a village chief that she wouldn’t leave her house and wouldn’t tell any of us what had happened. We had to spend hours talking to her, and counselling her, before she could go back to doing her job,” says Joshi.

Meera recalls reporting a story about a land dispute. “I was taking photos outside one man’s house. He took me inside, blocked the entrance of his house with a motorbike and said, ‘You like taking photos? Come, let’s take some photos in my bedroom.’ I managed to get out and call the police.”

For the Khabar Lahariya staffers, working at the newspaper has transformed their lives. “It is my dream job,” says Sharma. “The villagers were not supportive at first, but now they say, ‘You’re the first woman from our village to do this kind of work.’ They cut out my articles and frame them and put them up on the walls. Young girls in the village come to me and say, ‘Sister, we want to be like you.’ It makes me very proud.”

*Surnames not included at the request of the women, who feel using them leads to caste-based discrimination