Photograph: Philimon Bulawayo/Reuters

Local mistrust is slowing take-up of simple innovations that use sunlight to disinfect water, a UK conference has heard.

Researchers working on low-cost, low-tech water purification systems for developing countries are struggling to convince local people that their solutions work, the EuroScience Open Forum heard last week.

This is because most communities prefer to use known technologies, such as ceramic filters and chemicals, to clean their water and make it safe to drink, scientists said.

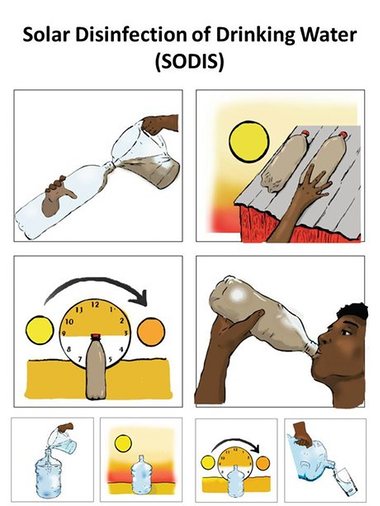

Kevin McGuigan, a researcher at the Royal College of Surgeons in Ireland, has developed and tested a solar water disinfection (Sodis) technique that involves filling a clear plastic bottle with water.

The sun’s heat and ultraviolet rays kill all harmful pathogens in the water in just a few hours, he told the event. But many people who could benefit from the technology are sceptical about its use, he said.

“Scientists need to ask themselves: ‘Where can the end-users get information from and how can we address scepticism?’” he said. “We do not think enough about this. That’s why solar disinfection remains among the least-used technologies in this field.”

McGuigan urged engineers and innovators to work with social scientists to address such issues. “We cannot only rely on [disinfection] science,” he said. “We must also consider the social factors to sell our technology.”

His colleague, Pilar Fernández-Ibáñez, a researcher at the Plataforma Solar de Almería, a solar research centre in Spain, told the conference how a lack of information about the markets for solar disinfection had caused scientists to focus incorrectly on efficiency rather than cost.

Work on using curved mirrors that focus sunlight to amplify its power had become overly complicated as researchers tried to make improved collectors that tracked the sun, she said.

“Using movable collectors improved efficiency, but made the technology much more expensive,” she said. “In the end, we went back to working on static collectors that can be manufactured in series at a small cost.”

The scientists on the panel said solar technologies are ideal for water purification as countries with the greatest need for cheap ways of disinfecting water usually have plenty of sunshine. Solar power is also relatively cheap to install and simple to maintain, the panel agreed.

To ensure that such technologies get taken up, scientists should think about hybrid solutions that address scepticism among users and improve on existing technology, the audience heard.

“For example, we are now trying to combine our solar disinfector with a ceramic filter,” McGuigan said.