Eighteen months ago the IOC’s “Olympic family” gathered in Monte Carlo. “There could not be a more symbolic host,” said the president, Thomas Bach, in his address, “than his serene highness Prince Albert of Monaco,” the monarch of a state memorably described by Somerset Maugham as a “sunny place for shady people”. It was an extraordinary session, called to address “the challenges we are already facing and, more important, the challenges we can already see on the horizon”. Bach was not referring to Russia’s state doping regimen, or Rio’s readiness for the 31st Summer Games which begins a week on Friday, but another problem entirely, one that, to the International Olympic Committee’s hive mind, felt altogether more pressing. While those two headline issues have damaged its brand, this third, far less reported, may ruin its business.

Two months earlier, Oslo had cancelled its bid for the 2022 Winter Olympics because there was so little public support for it. Earlier in the year, Stockholm withdrew for similar reasons. Krakow also cancelled after a referendum found almost 70% of residents opposed the bid. For Munich’s bid, the figure was nearer 60%. For Davos, it was 53%. In Barcelona, the mayor deferred until 2026, then canned the plan altogether. A similar thing happened in Quebec City. So from nine candidates, the IOC was left with two potential hosts. One was Almaty, in the dictatorship of Kazakhstan, and the other was Beijing, not hitherto noted as one of the world’s great winter sports resorts. Beijing won, though most of the events will be held 140 miles away in Chongli.

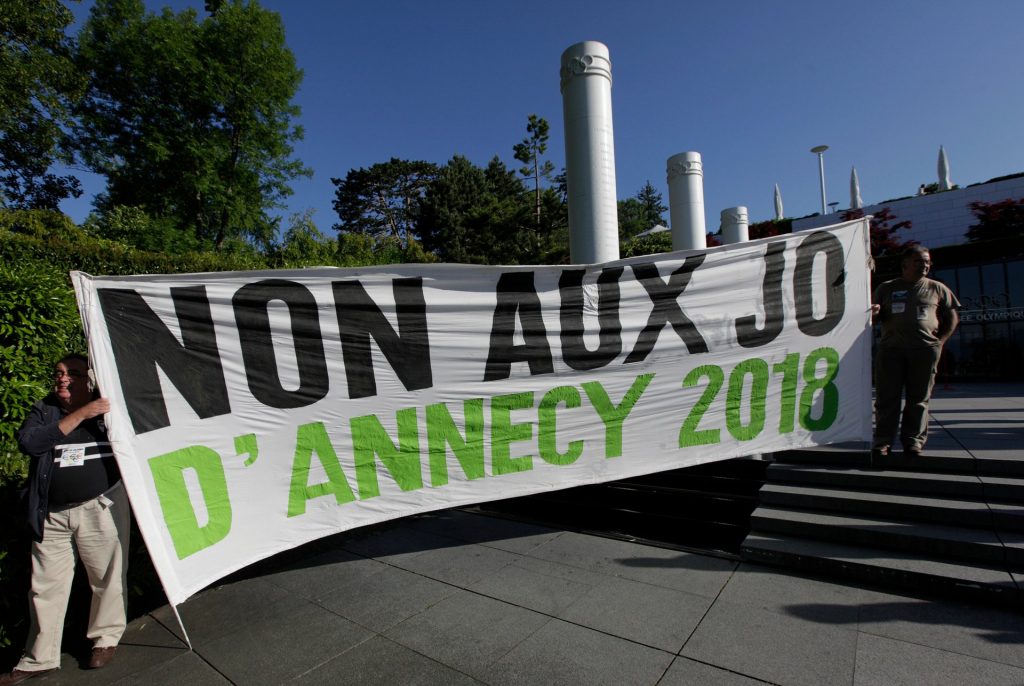

It is not just the winter cities with cold feet. In 2015 the US nominated Boston for the 2024 Summer Games, until Boston withdrew because of low public support. Germany nominated Hamburg but it pulled out after the local government lost another referendum. Toronto’s mooted bid was scrapped when its economic development committee voted against it. Right now, the four candidate cities are Rome, Budapest, Los Angeles and Paris. In Hungary, the supreme court has just blocked a proposed referendum. And in Italy, Rome’s new mayor, Virginia Raggi, has repeatedly said she opposes the bid, and the Italian Radical Party has been gathering signatures needed to force a referendum.

You do not need to be an academic to spot the pattern. But Christopher Gaffney is – a senior research fellow at the University of Zurich, he is a prominent voice in the anti-Olympic movement – and he describes it this way: “Wherever we see an educated population that has a relatively free press, relatively high levels of governmental transparency, and that has put it up for a referendum, in every one of those cases we have seen the Olympics be rejected. Without exception.” In the west, at least, it seems no one wants to play host anymore.

The IOC has been in a similar position before, after the disastrous Montreal Games in 1976. It took Montreal 30 years to pay off its Olympic debt. The upshot was that Los Angeles was the only city in for 1984. Because it was the only bidder, it was able to dictate terms. So the IOC was cut out of all the TV and sponsorship deals but it was able to turn to the sizeable profits LA made to its own advantage in other ways. It used it to incentivise other cities to bid. Five applied to host in 1992. Eight in 2000. Eleven in 2004. The IOC became “a monopoly rights holder of a business that seeks to extract rent from cities”, as Gaffney puts it. “They depend on having a group of cities competing against each other, raising the stakes.”

Where there was resistance, it came from the fringes. In Amsterdam protesters posted bags of marijuana to the IOC’s officials, then pelted them with eggs and tomatoes when they appeared in public. In Berlin a coalition of “anarchists, dropouts, punks, gays and lesbians, the alternatives, the stone-throwers, the fire-eaters, the grafters, the poor, the drunkards and the madmen” marched in the streets when the IOC made its final inspection of the city. The difference now is Olympic resistance has become mainstream. “What we’re seeing,” Gaffney says, is that “the more information citizens have about how the IOC works, the less likely they are to want to engage in that kind of business contract”.

Chris Dempsey was one of the leaders of the No Boston Olympics campaign. He once worked at the management consultancy Bain, and had been an assistant secretary of transportation for Massachusetts. “We were the people that showed up to meetings with suits on and power point presentations,” Dempsey says. “We were comfortable working on the inside, so to speak.” Dempsey and his group simply saw it is a question of civic priorities. “The Olympics would be a huge net cost on our city and our state, in that if our governor and mayor were focused on building a stadium and building a velodrome, they were going to be less focused on improving education and fixing roads.” It was, Gaffney adds, “a clear-eyed, pragmatic, American way of looking at this, to say: ‘We’re not going to spend tax money on hosting a three-week party.’”

Over the course of two months early in 2015, public opinion in Boston completely flipped. In January it had been polling 54% in favour of the bid. By March, the figure fell to 38%. In between, No Boston Olympics picked apart the details of the bid, cut through the “glossy brochures showing how the venues would look” and made it clear “the taxpayers were on the hook”. The Boston bid became untenable. Dempsey says it was “a reaction to the excesses of recent years. Especially Beijing but also London, because when you look at what was actually spent on those Olympics it is something like four times the original budget.”

In Hamburg, on the other hand, the anti-Olympic movement was rooted in the left. Florian Kasiske ran the PR for the NOlympia campaign. “There was a spectrum,” he says. It combined students, young members of the left-wing parties and a lot of harbour workers who were against the Olympics too, because their jobs were being threatened.”

Kasiske says one of the big issues was the gentrification of the city, especially around the harbour. “The Games are a big motor for displacement of poor people from inner city areas.” The other was the immigration crisis. “The people kept asking: ‘How can we organise the Olympics when we have to find housing for so many of the people who have come to the city? These people are sleeping in tents, and the politicians want to make a new velodrome?”

Photograph: Denis Balibouse/Reuters

In Boston and Hamburg, small, well-organised protest movements faced down powerful political and corporate coalitions. “The people that were pushing the bid were people that stood to benefit,” Dempsey says. In Hamburg, NOlympia overcame a bid backed by the mayor and the chamber of commerce. Both cases reflected Gaffney’s view the Olympics have become about “the selling of the city by the city’s own elites”. The more information the public have about all this, he says, “the less likely they are to want to engage in it”. Dempsey agrees: “Cities are starting to understand the IOC’s demands are unreasonable.”

“The IOC only have power if cities show up to bid. Eventually it may come to a breaking point where the IOC has to make real reforms.”

In Monaco Bach introduced Agenda 2020, a plan to reduce the barriers to bidding. Dempsey suggests it is not enough. “I would question whether moving to a different city every four years is really a model that makes sense in today’s world. Maybe in the 1890s it made sense but you are now in a world where 99.9% of people that engage with the Olympics do it on a screen.” He believes the Games should have a single permanent host venue.

Gaffney is more radical. “The same mistakes are made over and over again. So it can’t be an accident and if it’s not an accident, then we have to realise that the IOC’s business model is noxious,” he says. “We need to have a serious rethink about the way these events drive inequality on a global scale. And the best way to do that is to stop them. Full stop.”