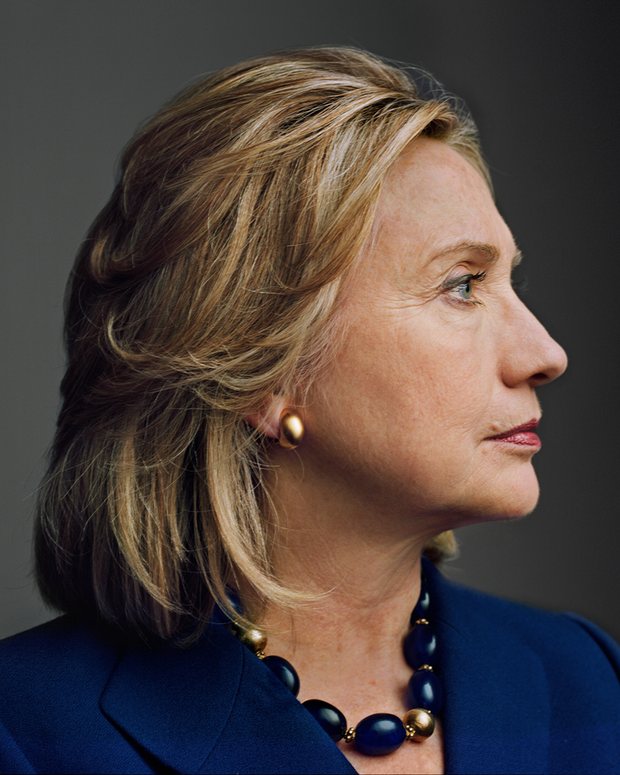

Radiant in white, Hillary Clinton greeted the cheering mob at the Brooklyn Navy Yard, most of whom had waited hours in the wilting June heat to see history made. Inside what used to be a giant greenhouse, fathers held up their daughters to catch a glimpse of the stage where, they fervently hoped, stood the first American woman to be elected president. There were plenty of gray-haired women who had worked as volunteers in Clinton’s unsuccessful 2008 presidential campaign, enjoying sweet vindication. “I’ve waited my whole life for this,” one told me. “I wouldn’t have missed it for the world.”

In her second quest for the Democratic nomination, Clinton has been much bolder in emphasizing her gender. Her entrance was preceded by a short film featuring the suffragettes, who won the right to vote in 1919, on the very day Clinton’s mother, Dorothy Rodham, had been born. “It may be hard to see tonight,” Clinton began her speech, “but we’re all standing under a glass ceiling right now.”

The line echoed a sadder day in 2008, when a vanquished Clinton endorsed Barack Obama. In defeat, she told her supporters: “Although we weren’t able to shatter that highest, hardest glass ceiling this time, thanks to you, it’s got about 18 million cracks in it.” She was warm and human, and many in the crowd were left musing, “If only she had been like that in the campaign.”

Photograph: Drew Angerer/Getty Images

In the intervening eight years, Clinton replayed the mistakes of 2008: her many failings as a politician (the critique that she was too brittle and unemotional); the constant infighting between her staff; the fact she misjudged the delegate math; and the lack of a coherent strategy or message. One of her aides described the 2008 campaign to me as “totally dysfunctional”, adding “it was often unclear who was actually in charge”.

Perhaps the most dysfunctional moment came right before that well-received concession speech. Some of Clinton’s current advisers still talk about the melodrama that played out until almost dawn. It deserves a full recounting, because it explains much about what went wrong, and Clinton’s disciplined course correction for 2016.

A battle royale over the concession speech dragged on for days, so long that one aide compared it to the cold war-era Strategic Arms Limitation talks. As in other fights, this one pitted her male strategists, including pollster Geoff Garin and Howard Wolfson, her bulldog of a communications director, against some of the women, including campaign manager Maggie Williams, brought in late to restore order and bring some humanity. Williams was a close friend of Clinton’s who had worked for her when she was first lady, and even earlier, when she was a young attorney at the Children’s Defense Fund. Bill Clinton, Hillary’s most trusted strategist, had his usual role as meddler-in-chief.

The main issues of contention were how heartily Clinton should endorse Obama, and how much of a focus there should be on her gender, something she had not emphasized in the campaign: her advisers were fearful that voters would see a female candidate as too soft, and question whether a woman could be entrusted with national security.

A draft went back and forth between the two camps, leaving it uncertain whether the cracking-the-glass-ceiling line, contributed by staffer Jim Kennedy, would survive (the outcome supported by the women) or be killed (the outcome preferred by the men). But Clinton loved it and approved a draft that night.

Enter her husband, who fancied himself as a good editor. He jumped in, made some changes and his draft went back to Clinton hours later.

“What’s this?” an annoyed Hillary asked. Told that it came from her husband, she replied: “It’s my speech.”

It was important to Clinton that she directly address her female supporters, who had desperately wanted, for history’s sake, to see her nomination at the Democratic convention. So she and one of her speechwriters hammered out a final version. When she stood inside the marble, cavernous ballroom of the National Building Museum the next day, barely a mile east of the White House, she uttered the glass ceiling line and the crowd went wild.

•••

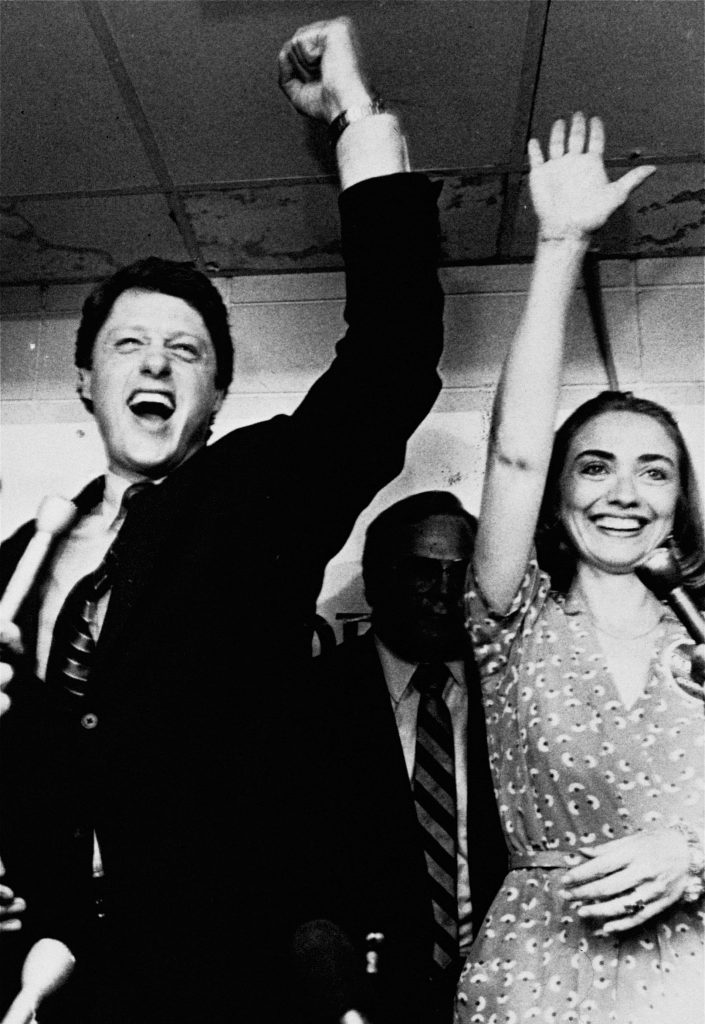

I have watched Hillary Clinton in her various political roles since she became first lady of Arkansas in 1979. Back then, she was still Hillary Rodham and I was a freelance copywriter for a political consulting firm, one that created advertising for her husband’s first campaign for the governor’s office. When I became a political and legal reporter, I spoke to her every now and then on matters involving case law, and the status of women in the law. At the Wall Street Journal, I was an investigative reporter covering money and politics; I was told by a senior White House staffer that Clinton took offense at an article I had written in 1992 about the “FOBs”, the Friends of Bill, an impressive network of donors that the Clintons had built. Apparently, Bill liked the piece; Hillary thought it made them look as if they were using their friends.

When I left the Journal to do investigative work at the New York Times, I wrote articles that were critical of Kenneth Starr, the independent counsel who led the investigation that triggered the unsuccessful drive to impeach Bill Clinton over the Monica Lewinsky scandal. Nonetheless, when I held the most senior editing jobs at the Times, I was told by two of Clinton’s press aides, and by reporters who covered her, that she thought I was biased against her. She blamed me for the Times’ tough coverage of the Clinton Foundation, scrutinising the murky conflicts of interest as international donors and old contacts backed pet projects, as well as other stories, including one about her marriage that said Bill and Hillary’s schedules rarely put them in the same location.

This history reflects Clinton’s wariness of the press (bordering on loathing) and what some friends describe as a streak of paranoia. She did not agree to an interview for this article, and while some of her closest allies agreed to be quoted, none would go on the record saying anything even mildly critical. I found the same dynamic back in 1992: people close to her feared banishment from Hillaryland if they talked to the press.

This account is based on interviews done over the past months, and on my own observations from watching Clinton on the campaign trail, from Arkansas to now. When I met Clinton in 1978, she did not seem like a politician, especially compared with her exuberant husband, who was always running late and couldn’t stand to leave a hand unshaken. He was the most likable candidate I had ever met. She was smart, on point, and didn’t like to have her time wasted. She was considerably less warm, though I have since spent time around the charming, funny Hillary. Almost everyone around her today admires Clinton’s resilience, and tells me she has improved her political skills, up to a point; but they also share her own assessment – that she will never be a political natural like her husband.

•••

Rather than wallow in the mistakes of 2008, Clinton went to school on everything Barack Obama had done right, meeting and grilling some of his top strategists, including Jim Messina, who went on to deliver a second Obama win, and a UK general election victory for David Cameron. In September 2014, she had a long meeting at her home with David Plouffe, Obama’s campaign strategist, who told her she had to have a first-rate data analytics team, a key advantage for Obama in 2008.

In her second presidential campaign, there has been little infighting and no hesitation to stress gender (“Deal me in!” was her memorable reaction to Donald Trump accusing her of “playing the woman card”). She has taken more direct control, including the tactical decision to give her dogged rival Bernie Sanders almost everything he wants in order to unify the party. She has ignored the lingering criticism that she is a boring egghead, and instead embraced her policy wonk tendencies. While Trump has confounded with his superficial and often contradictory statements, Clinton has been prosecuting the argument that testing times demand a leader with grip and knowledge.

Photograph: Win McNamee/Getty Images

“Doing policy is smart,” Richard Billmire, a longtime Republican consultant who is no fan of Clinton’s, told me. “She’s projecting the commander-in-chief thing well.” She leans hard on her adviser Jake Sullivan, a former Rhodes scholar who served as her director of policy when she was secretary of state, and then as Vice-President Joe Biden’s chief of policy. Sullivan has long been her “go-to guy”, and was a favorite to be national security adviser in a Hillary Clinton White House; this is now complicated by the fact he sent some of the emails at the heart of the investigation into her use of a private server.

On the 2016 trail, it was Clinton’s call to attack Trump early and hard. Her cogent diatribe against the Republican candidate’s ignorance of foreign policy in San Diego, right before the California primary, was by far her best speech this year, reflecting her comfort with portraying her opponent as dangerous for America. This time, no one is asking whether Clinton is tough enough.

She has grown surer of her own judgment, a certainty that is both her greatest strength and weakness. Once Clinton has made up her mind, it is extremely difficult to change it. Dissent isn’t welcome, one former White House official told me; he doesn’t think she would be a good president, because she “can’t stand hearing people say she’s wrong”. It’s not that she’s thin-skinned (one of her criticisms of Trump) or uncollaborative (she was known for working well with Republicans in the Senate, and with generals at the Pentagon); she just knows that she’s right.

•••

Right after the concession speech in 2008, Clinton left the Great Hall to meet and thank her staff. She began sending out thank-you notes from an office she set up in downtown Washington DC. There, she focused on putting a dent in her campaign’s $22m debt. According to HRC, a book about this period by Jonathan Allen and Amie Parnes, Clinton and her aides kept a master list of every major Democrat who had supported her, and those who had endorsed Obama. Missouri senator Claire McCaskill, in the Obama column, was marked down as the worst traitor of all for a nasty quip about Bill (she said publicly that she wouldn’t trust him around her daughter).

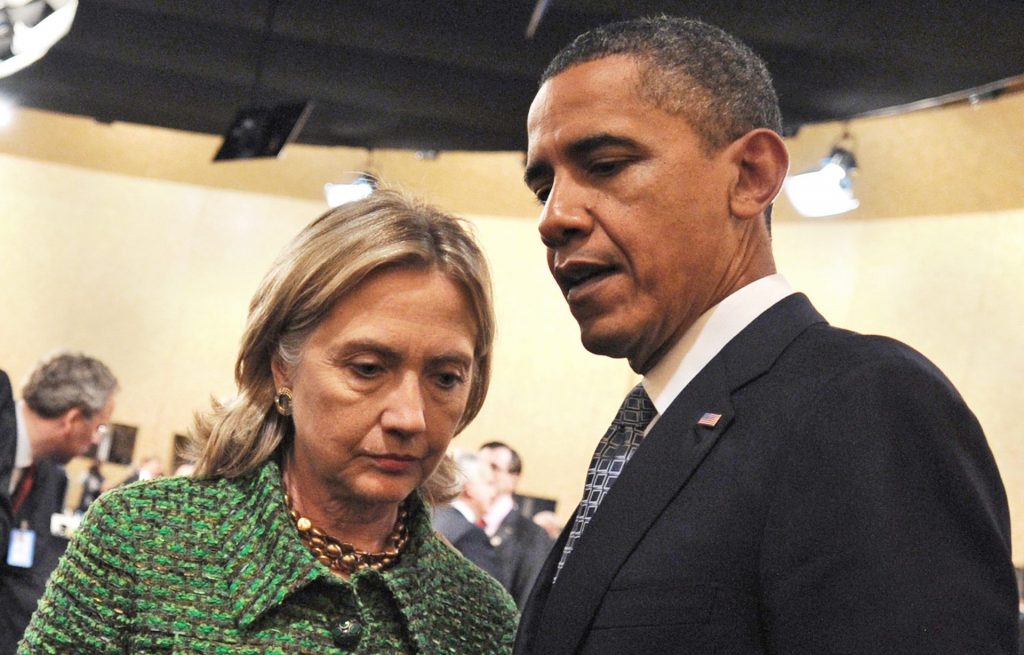

Photograph: Rainer Jensen/EPA

Then came the call from Obama, within days of his election, to ask Clinton to be his secretary of state. “She did not make the decision to say yes easily,” a long-time aide recalled. “It was a hard transition to go to work for the man that beat her.” Clinton said no the first two times. “She wanted Obama to grovel a bit,” another former White House aide told me.

The third time Obama offered her the job, she accepted. Her main concern was her freedom to hire, and she brought over many members of Hillaryland, including former White House lawyer Cheryl Mills and former chief of staff Melanne Verveer. She also kept in touch with her aides, instructing them not to brood over how it ended. “There’s too much work to do,” she’d tell them.

For the most part, Clinton and Obama had a cordial but somewhat distant relationship. A loyalty nut herself, Clinton was determined not to undermine the president. On a few occasions, she got annoyed at White House staff, especially when they tried to block her pick, Capricia Marshall, for an important state department post. Obama overruled them and approved the appointment. Still, Clinton planned to stay for only one Obama term.

No one I interviewed said Clinton spoke to them about whether she planned to run again. She keeps her political cards very close and confides in few people about her career or her personal life. “I am not the type of person who routinely pours out her deepest feelings, even to my closest friends,” she wrote in her first book, Living History. “My mother is the same way. We have a tendency to keep our own counsel.”

Once she joined the Obama cabinet, Clinton talked little of politics at all. “She has a great ability to compartmentalize,” said a friend. If she confided in anyone besides her husband and daughter, several friends told me, it was her mother, who lived with her in Washington DC while she was secretary of state. The two enjoyed watching television together, especially Dancing With The Stars. Her mother’s death at 92, in 2011, hit Clinton hard, because Dorothy was the one who always reminded her of the importance of resilience. In one of her speeches, Clinton said: “I can still hear her saying, ‘Life’s not about what happens to you, it’s about what you do with what happens to you – so get back out there.’”

Photograph: Ron Frehm/AP

As secretary of state, Clinton’s poll numbers shot up. Rebecca Traister, author of Big Girls Don’t Cry, a fascinating study of sexism in the 2008 campaign, observed: “It was easier to embrace this woman in a state of diminished power, once she had lost the big prize. Her favorability ratings were above Obama’s. Gallup found her the most admired woman in America.” Clinton became the most travelled secretary in history – almost 1m miles – as she tried to restore America’s international reputation following the Bush years, but the pace was exhausting, and constantly being on planes hurt her health. At the end of 2012, a stomach bug left her dehydrated and Clinton fainted; the resulting concussion left her with vision problems for weeks.

Her health recovered, and towards the end of her tenure at Foggy Bottom, as the state department is known, Madam Secretary purposely projected a hipper, funnier image, opening a Twitter profile that at the time said: “Wife, mom, lawyer, women & kids advocate, FLOTUS, US Senator, SecState, author, dog owner, hair icon, pantsuit aficionado, glass ceiling cracker, TBD…”

Clinton was enjoying the benefits of a more approachable image, although the events of those final months in post would cast a shadow all the way to election year. The deadly attack on the US consulate in Benghazi, in which the US ambasssador to Libya and three other Americans died, triggered many subsequent investigations and hearings, and led directly to the revelations about Clinton’s use of a private email server. An investigation into the mishandling of classified information ended earlier this month without charges, but there was a stinging rebuke from the head of the FBI, who called Clinton and her staff “extremely careless”.

Photograph: Pablo Martinez Monsivais/AP

It was only after she left office in early 2013 that she started thinking seriously about another run. “She began meeting with important Democrats,” said one of her current staffers, people such as Bill’s former chief of staff John Podesta and Jim Messina. There had been other, earlier indicators: on the night of Obama’s re-election in November 2012, an exploratory political action committee was established, called Ready For Hillary, made up of strategists and close friends. Somewhat surprisingly, Senator McCaskill of Missouri – deemed treacherous in 2008 – became its lead spokeswoman and one of the first lawmakers to endorse Clinton. She had been allowed re-entry to Hillaryland despite her disloyalty, a rare occurrence indeed.

•••

“Beaches and speeches.” That was Clinton’s stock answer to people who badgered her about her plans in 2013. She insisted she hadn’t made a decision, a claim that left her loyalists and the press corps skeptical. In December 2013, she and her husband flew to Oscar de la Renta’s palatial home in Punta Cana, a swank area of the Dominican Republic where the couple went every year. That was the beach part.

She signed on with the Harry Walker Agency, a well-known speakers’ bureau in Washington DC. A few of her advisers thought it was a bad idea to become a “buckraker”, but she justified it, pointing out that her predecessor Colin Powell earned million-dollar fees for the same thing. Why should she have to be the exception? Clinton often bristles over what she views as an unfair, sexist double standard that requires her to be cleaner than Caesar’s wife. It’s a resentment that also fuels her natural tendency zealously to protect a zone of privacy.

Clinton’s bent towards secrecy has repeatedly gotten her into political trouble. First, the early scandals, such as an investment in the Whitewater land deal in Arkansas, only really remembered by the most implacable anti-Clinton obsessives. Then there was her refusal to reveal billings for her clients at the Rose Law Firm in Little Rock when Bill was Arkansas governor. She would not reveal the names of lobbyists and others who met with her when she was crafting the Clinton healthcare plan, known as Hillarycare, when asked by journalists or Republicans in Congress. Most recently, she has refused Bernie Sanders’ demands to release the text of her money-making speeches to Wall Street banks.

Money is another area where Clinton can be tin-eared. One lifelong friend told me that Hillary is haunted by her time in Arkansas, when she was the breadwinner (her husband’s salary as governor was only $35,000). After he unexpectedly lost a bid for re-election in 1980, the couple had to leave the governor’s mansion for a small, drab place. Although I don’t buy it, this friend said fear over sudden “poverty” explained her lust for the speaking fees, for which she and her husband have earned an astonishing $139m over the last eight years. The home they bought in Chappaqua, New York, after leaving the White House cost $1.7m, while Whitehaven in Washington DC cost nearly $3m. Her description of being “dead broke” after they left the White House made her look out of touch.

Photograph: Justin Sullivan/Getty Images

Clinton’s pledge to relax more and tend to her health left advisers such as Cheryl Mills and Maggie Williams free to tell her that she should simply retire from politics, at the top of her game, and enjoy time with her new granddaughter, Charlotte, who was born in September 2014. “She wanted a grandchild more than anything,” one of her close advisers told me. On the road in 2016, now 68 years old, Clinton has Skype calls with daughter Chelsea and her grandchildren (Chelsea gave birth to a son in June). Because Bill and Hillary used to Skype with Charlotte before the campaign, the toddler’s eyes sometimes wander off during the calls, looking for her grandad.

Whatever temptation there was for a slower pace, however, has clashed with Clinton’s belief, bordering on missionary zeal, that she has been called to public service. (An early New York Times magazine profile of her in 1993 when she was first lady was headlined “Saint Hillary” and captured her faith in “a politics of virtue”.) James Carville, who masterminded Bill’s 1992 presidential campaign and starred in a documentary about it, The War Room, told me he was certain she would run again. So were many others. The lack of a strong rival (or so Clinton thought, until Sanders came along) made another bid enticing.

So no one was terribly surprised when, on 12 April 2015, Clinton announced, via video, that she was running. The next month, surrounded by her family, she held a rally on Roosevelt Island in New York. At the end of May, Sanders launched his own bid, but was soon overshadowed by fevered speculation over whether Senator Elizabeth Warren, another liberal firebrand, might jump in.

Clinton focused on hiring her campaign staff. As well as the Obama campaign, she had spent a great deal of time studying another, her friend Terry McAuliffe’s successful bid in 2013 to be governor of Virginia – a win in a swing state where Republicans had held the governor’s mansion. Clinton hired many from McAuliffe’s team, selecting his campaign manager, Robby Mook, as her own. Mook, 36, is less showy than Bill Clinton’s Carville, or Obama’s Rahm Emanuel, but he is viewed as a talented tactician who understands data; while still in his 20s, he helped orchestrate some primary wins for Clinton in 2008.

Photograph: Zuma Wire/Rex/Shutterstock

Clinton hired Obama’s pollster Joel Benenson, and others who had worked against her in 2008. Gone were Clintonites such as Mark Penn, a controversial pollster whose private business interests became an issue in 2008. Mandy Grunwald, a talented ad-maker, was one of the few longtime loyalists advising her. Very soon, she had a large paid staff that would balloon to more than 700 by the end of the primaries. (Trump, who claims to have mostly self-funded his quest for the Republican nomination, has about 70.)

When I visited Clinton’s Brooklyn headquarters in May, I was surprised to see how much younger her campaign aides were compared with the previous team. A poster of her in profile, looking like Joan of Arc on the 2008 trail, seemed to be everywhere. The campaign occupies two floors of an office building near the courts, and the most important advisers are among the few to have private offices: chairman John Podesta, known for his grip of issues (Obama brought Bill Clinton’s former chief of staff back into the White House to drive through his second term climate change agenda in the face of a recalcitrant Congress), Jake Sullivan, and communications chief, Jennifer Palmieri (also plucked from Obama’s White House operation). The rest of Clinton’s staff sits mostly in the open; until recently, everyone was crammed on to one floor.

•••

In 2008, Clinton was criticized for acting like “the anointed one” on her campaign. Cold water was splashed on that notion very early in the race, when she came in a rather pitiful third in the earliest caucus state, Iowa, behind Obama and John Edwards. The biggest lesson she learned, she often said, was that she must “organize, organize, organize”. But 2016’s huge early Bernie Sanders rallies, filled with younger voters, tipped off her aides that she faced another tough climb in mostly white states such as Iowa and New Hampshire, and later in the midwestern Rust Belt.

Stylistically, Clinton was rusty. In the snows of New Hampshire in February, there was poignancy to Clinton’s losing effort. I watched her campaign her heart out in Manchester, in Dover and in smaller towns. She was trying hard to forge an emotional connection with the voters she met. A lifelong Methodist, she confided that she tries to read a piece of Scripture at dawn each day, emailed to her by a minister friend. In one televised debate, she was asked a philosophical question about how she retains some semblance of humanity while at the centre of the political fray. She quoted a line from a parable that she called her “lifeline”: “Practice the discipline of gratitude.”

In the appearances I witnessed, Clinton drew smaller crowds than Sanders, her events often held in high-school gymnasiums. I noticed that she was raising her voice louder and louder, something others falsely reported as screaming. She seemed to get louder when she wanted to energize her audiences, to get them to applaud and shout her name. At the packed Sanders events, the adoration came naturally.

The wobbly start hurt. Clinton was especially stung by the rejection from some younger women who didn’t seem that excited about the prospect of electing the first female president. She had devoted so much of her life to championing the welfare of women and children, and was now openly brandishing her feminism; it was hard for her to understand why young women were so stirred by the 74-year-old Sanders.

Photograph: Andrew Harnik/AP

The Clinton playbook was to do the opposite of 2008. But a member of her communications staff conceded to me that there remains one unfortunate similarity: a lack of narrative or clear message that sums up why she is running for president and where she will take the country. In 1992, her husband, advised by Carville and George Stephanopoulos, ran on: “It’s the economy, stupid.” Barack Obama, advised by David Axelrod, ran on “hope and change”. While Mook and Podesta are extremely able, they are not political gurus, and Clinton has struggled to articulate her vision in a handful of words.

“We don’t have an Axelrod,” the aide told me. It’s unclear if anyone might yet be found to fill that gap.

Of course, Clinton’s main adviser, her husband, thinks he is that person. Another campaign official told me that the two speak on the phone at least once a day. But Bill has been less visible than in 2008, when he marred the campaign (and his own reputation) by calling Obama’s message a “fairytale” and drew criticism for suggesting “white Americans” were turning away from his campaign. More recently, Bill inflamed the email controversy when it was reported that he had met the attorney general, Loretta Lynch, in an Arizona airport just days before a decision was made on whether to prosecute Hillary. Lynch was forced to say she would follow the recommendation of the prosecutors and FBI officials working on the investigation.

According to the 2007 book Her Way, by Jeff Gerth and Don Van Natta, the Clintons have what they call “a 20-year pact” from their Yale law school days. They both expected to be elected president, even if that dream took decades to achieve. Connie Bruck, who wrote an insightful profile of Hillary Clinton in the New Yorker in 1994, had a two-hour White House interview with Bill, where he gushed over what a great president his wife would make. The idea was dismissed at the time. It doesn’t seem far-fetched now.

•••

Clinton’s best political moment this year was in San Diego, right before the California primary. Flanked by more than a dozen American flags, she looked very much the commander-in-chief. Her speech clearly outlined her foreign policy goals: a strong, confident America engaged with the world, “to keep our country safe and our economy growing”. But the speech will be remembered for her scrupulously factual and devastating recitation of Trump’s most ignorant and outrageous statements about global issues. “They’re not even really ideas,” she said, “just a series of bizarre rants, personal feuds and outright lies. This is not someone who should ever have the nuclear codes – because it’s not hard to imagine Donald Trump leading us into a war just because somebody got under his very thin skin.”

Photograph: John Locher/AP

The speech took 10 days to craft, with Clinton involved. When she read aloud the litany of Trump’s statements, she turned to her speechwriters and asked in mock disbelief, “Can he really have said all these things?” At subsequent California campaign events, every time she mentioned the San Diego speech, the crowd spontaneously erupted in applause and cheers. This time, she did not need to raise her voice.

In New Hampshire earlier this month, after a tetchy campaign season, Sanders and Clinton finally joined forces as he endorsed her – they even hugged – speaking from a lectern decorated with a “Stronger Together” logo. On the trail, Sanders had questioned her judgment and fitness for office, but in endorsing Clinton, he called her a first lady who had broken precedent, a leader in the fight for universal healthcare, “a fierce advocate for the rights of our children” and declared her “one of the most intelligent people that we have ever met”. Thumping the lectern, he proclaimed: “Hillary Clinton would make an outstanding president, and I am proud to stand with her today.”

It wasn’t picked for this reason, but at Balboa Park, where Clinton spoke in San Diego, there is a large statue of a Mayan woman. That ancient culture records women among its most powerful leaders. Next week at the Democratic convention in Philadelphia, it is finally Clinton’s turn, with two past presidents – her husband and Obama – appearing in service of her nomination as the party’s presidential candidate. She will tell Americans she is ready to lead and, in November, hopes finally to take a hammer to that last glass ceiling.