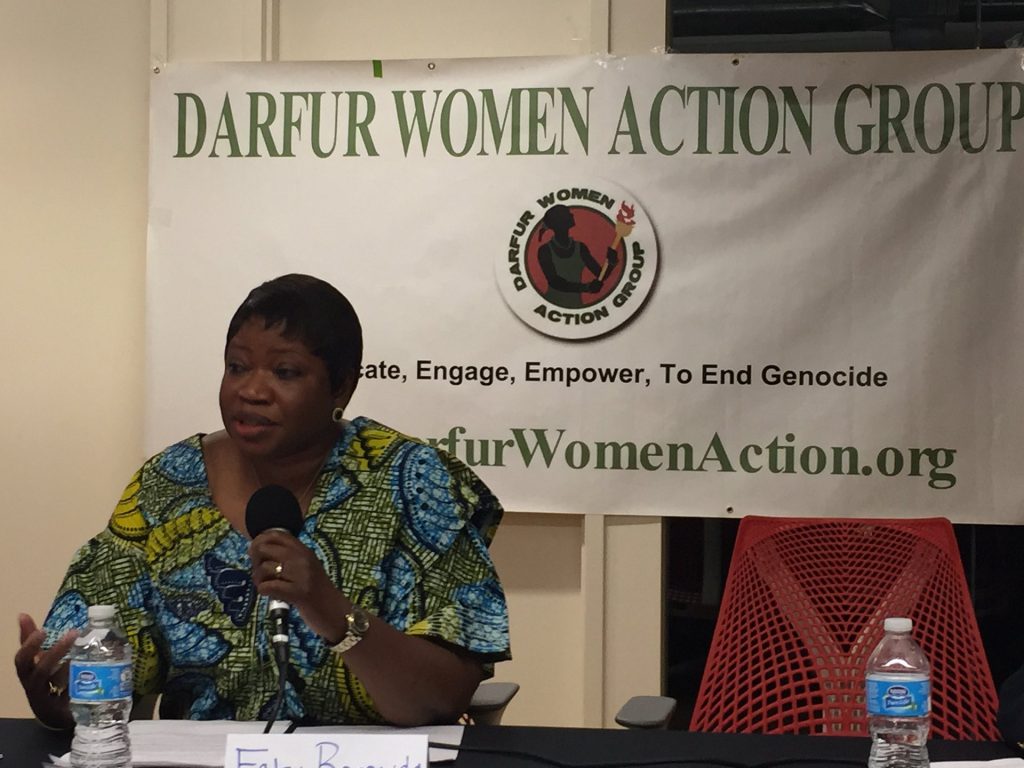

Photograph: Yoshihiro Ikeda/Courtesy of ICC

In popular accounts, Africa and the international criminal court are pitted against each other. The ICC is derided as being “biased” against Africa, ignorant of the attitudes and desires of Africans, even neocolonial.

In reality, the relationship suffers from misinformation and misunderstandings. Many parties share responsibility for this. Some African leaders have, on occasion, decried the ICC in order to protect themselves from the court’s scrutiny.

Equally, the ICC has not been able to communicate its message effectively on the continent, leaving it susceptible to misrepresentation by those who seek to undermine the institution.

Some insist that the ICC has no place in Africa and that African states must withdraw from the court because the institution has intervened primarily in African conflicts, while situations outside the continent are not investigated. However, it makes little sense to suggest that because justice cannot be served everywhere, justice should not be served anywhere. Such an attitude insults victims and survivors alike.

Why has the ICC focused its investigations almost exclusively on Africa? Well, can anyone argue that the situations in Africa where the court has opened official investigations – northern Uganda, the Democratic Republic of the Congo, Central African Republic, Darfur, Sudan, Kenya, Libya, Ivory Coast and Mali – are not deserving of an ICC intervention?

In all these situations, local justice systems were either unwilling or unable to investigate and prosecute themselves. For the most part, the relevant governments invited the court and cooperated with its officials. In other cases, African member states of the security council voted in favour of referring the situations to the ICC.

Photograph: Courtesy of ICC

Why has the ICC not intervened elsewhere and, especially, in powerful states? The court is severely limited in its reach. While there have been recent calls for the ICC to act in Syria and North Korea, its jurisdiction prohibits it from doing so. Our group has consistently advocated universal ratification of the Rome statute to ensure justice and accountability around the world.

It is important to note that the ICC has now opened an investigation into the 2008 war between Georgia and Russia, the latter of which is a permanent member of the security council. The court also continues to examine allegations of international crimes on other continents, including claims of torture and enhanced interrogation techniques by US officials in Afghanistan and war crimes by British troops in Iraq.

Some argue that the kind of retributive justice offered by the ICC is inappropriate in Africa. Some even suggest criminal punishment may perpetuate conflict. In reality, burying grievances and injustices fuels unrest. Impunity for powerful perpetrators of mass atrocities risks undermining long-term stability and development.

Of course, no single approach to justice is sufficient. African communities can and should have a say in what types of mechanisms are most appropriate. But the ICC does not present itself as a magic bullet for peace or justice. It can only prosecute those most responsible for mass atrocities. Moreover, it has shown itself to be increasingly sensitive to the voices and desires of African constituencies.

In northern Uganda, many citizens have made it clear they do not want Lord’s Resistance Army combatants to be prosecuted. Instead, they want them to be integrated into their communities following a process of traditional justice. So the ICC’s chief prosecutor has assured LRA combatants that the court is only prosecuting Joseph Kony and Dominic Ongwen and has encouraged fighters to defect.

Never before has so much been done on the African continent to achieve accountability for international crimes. We welcome the trial of Hissène Habré in Senegal, Central African Republic’s plan to set up a special criminal court, South Sudan’s proposed hybrid tribunal, and the expansion of the jurisdiction of the African Court on Human and Peoples’ Rights to include international crimes.

While none is perfect in itself, these and other recent developments point to a continent with the potential to take a leadership role in international criminal justice, if its leaders keep their pledges.

These are also opportunities for us and the international community to share expertise and engage in respectful and context-specific judicial capacity-building projects.

The ICC must listen to constructive criticism. Many say the court is too close to the security council, whose three most powerful members – Russia, China and the US – are not parties to the Rome statute. The ICC prosecutor is not bound to accept security council referrals automatically and will independently ensure that the necessary legal requirements of the Rome statute are met, but it is difficult to accept that referrals for the worst crimes known to mankind can be made with caveats that exclude a number of potential players in those conflicts from the ICC’s jurisdictional reach.

Photograph: Courtesy of ICC

The ICC must do a better job of responding to overt attempts to politicise its mandate. It must not only do justice, but be seen to be doing justice by being more effective, robust and responsive.

African states are friends of the ICC. African states have continued to refer situations to the ICC. Africans hold the most senior positions in the court. African states fund the institution.

Many African officials and diplomats say they have no intention of leaving the Rome statute system. We call on these governments to speak loudly and courageously in the fight against impunity – both in Africa and beyond.

- The Africa Group for Justice and Accountability is an independent group of African experts from diverse backgrounds. The members are Dapo Akande, Femi Falana, Hassan Bubacar Jallow, Richard Goldstone, Tiyanjana Maluwa, Athaliah Molokomme, Betty Murungi, Mohamed Chande Othman, Navi Pillay, Catherine Samba-Panza, Fatiha Serour and Abdul Tejan-Cole