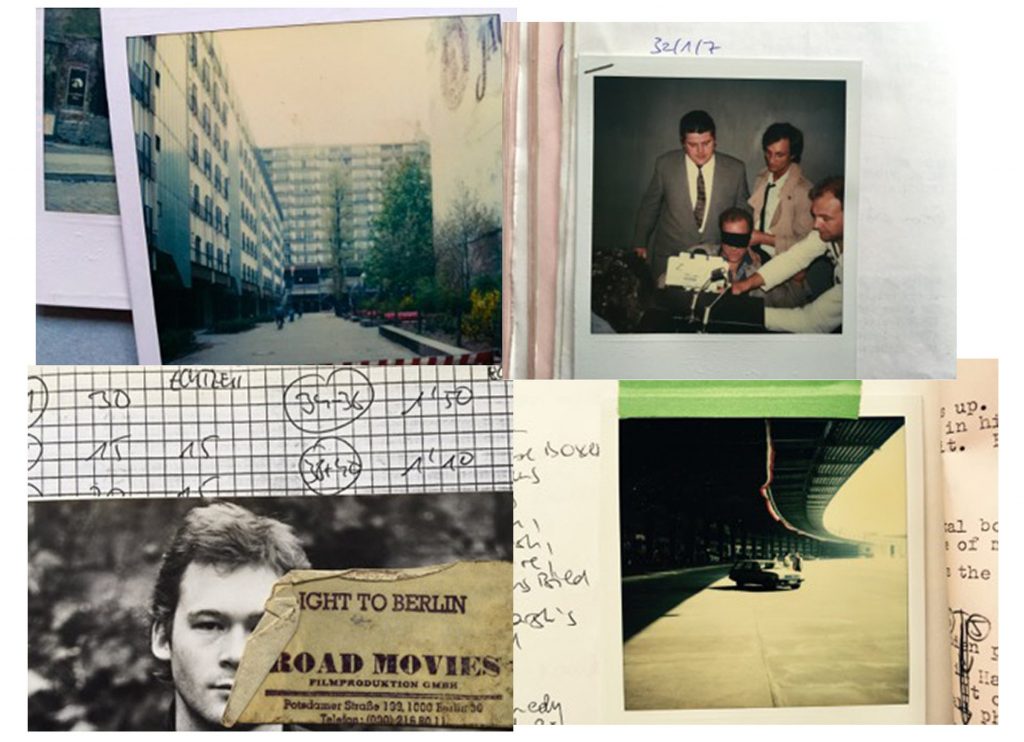

Composite: Chris Petit

It is 1984 and I’m being driven around East Berlin in a Jaguar XJ6, the only one in town. We are making Chinese Boxes, a cheap thriller with an incomprehensible plot about teenage drug deaths, Berlin gangsters and US intelligence. The film’s budget is about three quid and, to save money, it is being scored in East Berlin, hence the driver of the white Jag, who is its composer – and, we learn later, a Stasi informer. But it seems anyone who is anyone is. We drink red wine from Bulgaria and talk about the unthinkable, reunification, known then as the German spring.

In those days, I was living in West Berlin which, by contrast, was less a city than an advertisement for a controlled kind of hedonism: white powder, sex in taxis, vodka chasers. The nearest I got to thinking about the cold war was at end of a very long night when a white light I swore was the first nuclear flash was of course only the door of the club opening to show that outside it was already the next day.

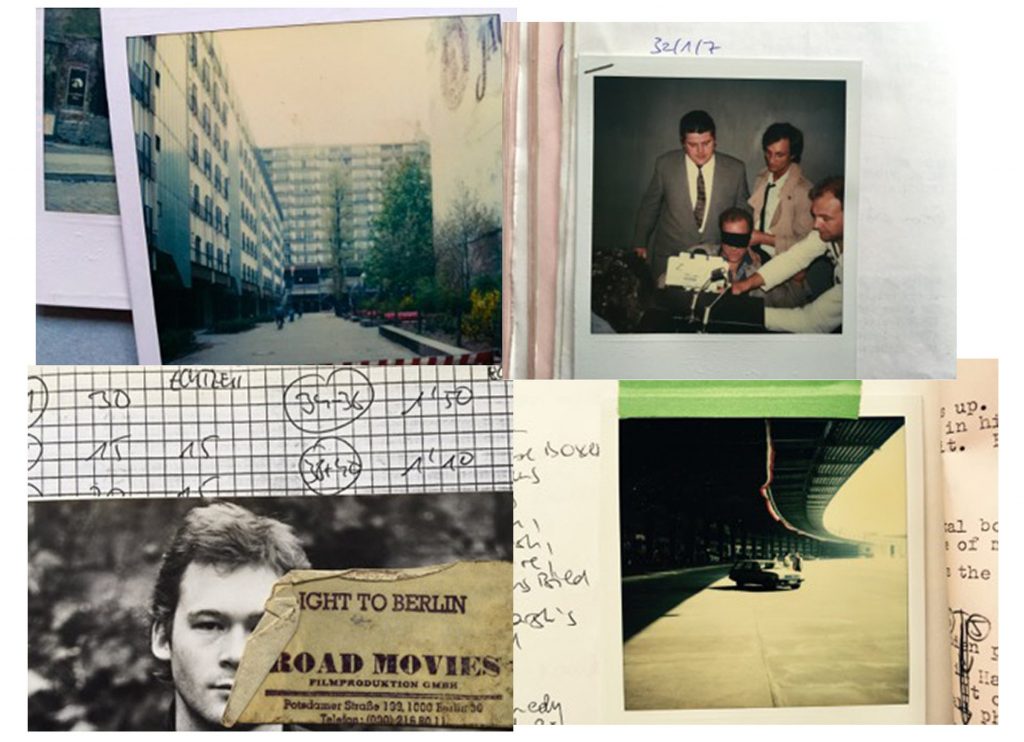

London closed at 11. In Paris, you could just about make it through to one. In Berlin, no one told you to go home, ever. Booze and amphetamine nights driving down empty streets with the white lines of the road appearing above the roof of the car. The car was an old VW with a faulty sunroof that could playfully dump the equivalent of a bucket of cold water down your neck, the only perfect cure for a hangover I have ever found.

Evenings started late and were marked by theatricality – and a cast of predatory men and feral women, the likes of whom you didn’t come across elsewhere. The gay quarter was a tamer version of Christopher Street in New York, very sub-Genet, in an area now almost exclusively dedicated to male couples with tiny dogs. Both heterosexual and homosexual excess seemed more willed than pleasurable, as if Berlin felt obliged to reignite Weimar decadence and blank what had followed.

It was a city of the young and the old – as the male professional classes were off in West Germany building their careers – with a lot of war widows and hairdressers. Residency in Berlin exempted young men from military service, even though it remained under martial law and military occupation, with capital punishment still an option.

Photograph: Chris Petit

I stayed in a room that faced a blank wall and got no sun. I was impressed because the apartment’s owner had his own huge photocopying machine in the hall. In terms of aspiration, though, the height of sophistication was an electric IBM golfball typewriter, one of the nicest machines ever designed. What we didn’t know was that IBM had once offered the Third Reich its latest punch-card technology to collate the national census, intended as the first step towards segregating the country’s Jews.

I was always more interested in Germany than England, after spending time in the late 1950s as an army brat in the garrison town of Iserlöhn, on the edge of the industrial Ruhr. Even at the age of eight, I was aware of perplexing questions about winning and losing. Beaten Germany felt strangely arrested, strangely progressive (Mercedes, Telefunken), more technological and complicated, and interestingly scarred by its psychological burden.

Photograph: Don McPhee for the Guardian

On a later trip back, I happened to pick up a book called The Last Jews in Berlin. We all knew about the trains and what happened next, but I knew nothing of the Germany before, a world of moral confusion and uncomfortable truths: how, for example, part of the twisted genius of the Third Reich was the way it solicited the cooperation of those it wished to destroy, first with the deportations and later in the camps.

The most extraordinary part of the book dealt with what were known as the snatchers: Jews who volunteered or were coerced to hunt down fellow Jews in hiding. Stella Kübler was the most notorious, barely out of her teens, alluringly beautiful and known as the blonde ghost. Vestiges of her lingered in the streets I found myself in: her beat scoured the theatres, cafes and bars of a part of Berlin I came to know well.

Meanwhile, the picture we were getting of Britain in 1984 was of a country on its knees (miners’ strike, embassy shootings) but when I went back I found London becoming a boom town. Flashed fivers had overtaken the pound note and there was a burgeoning restaurant scene – which really took off after the 1986 deregulation of the stock market, to accommodate aghast foreigners who found no gyms or decent places to eat.

I never particularly had it mind to write about Berlin back then. I went home and wrote Robinson, ostensibly a London Soho novel. Only a long time later did I realise that, without Berlin, I could not have written about London, my version of which – in terms of imaginative reality – was based more on the experience of Berlin, which in the late 1970s and early 1980s offered enough distractions to test the border zones of anyone’s identity.

- The Butchers of Berlin by Chris Petit is published by Simon & Schuster. The Psalm Killer is published as a Picador Modern Classic.