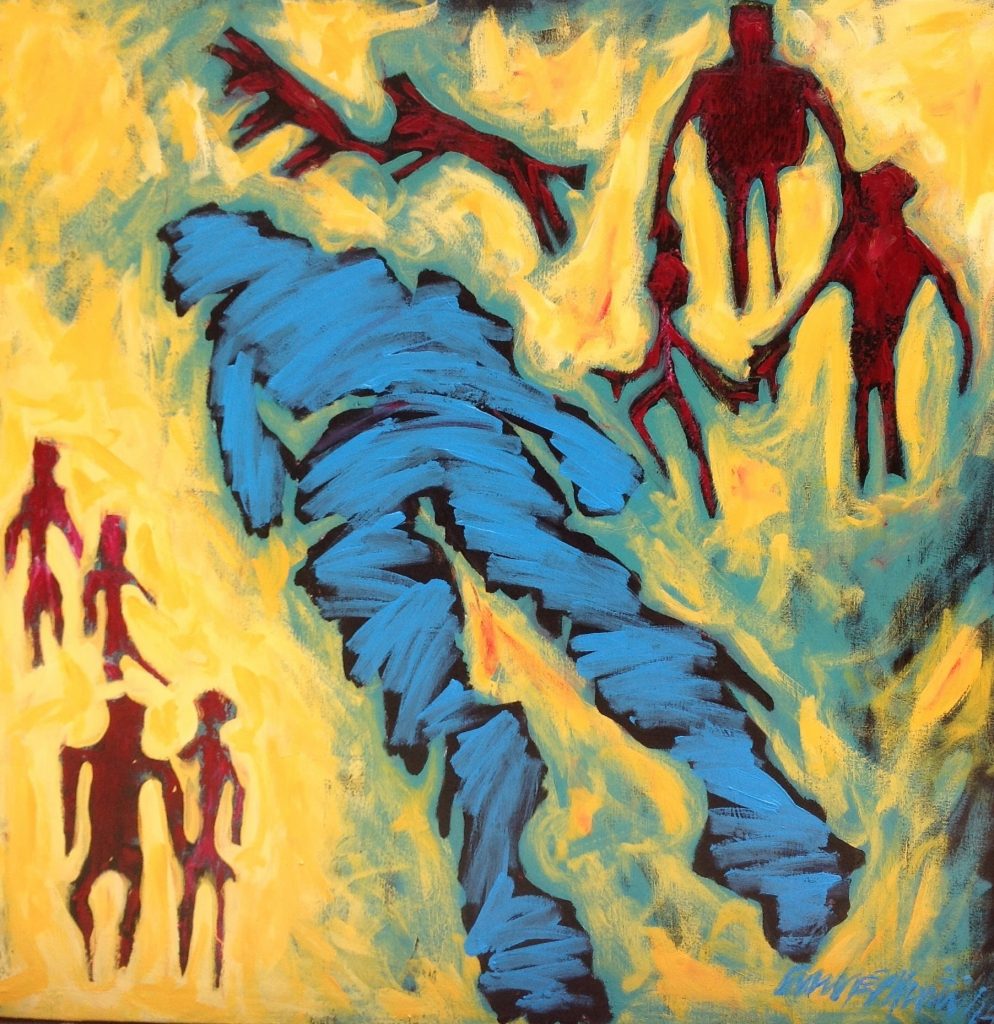

Photograph: Longinos Nagila

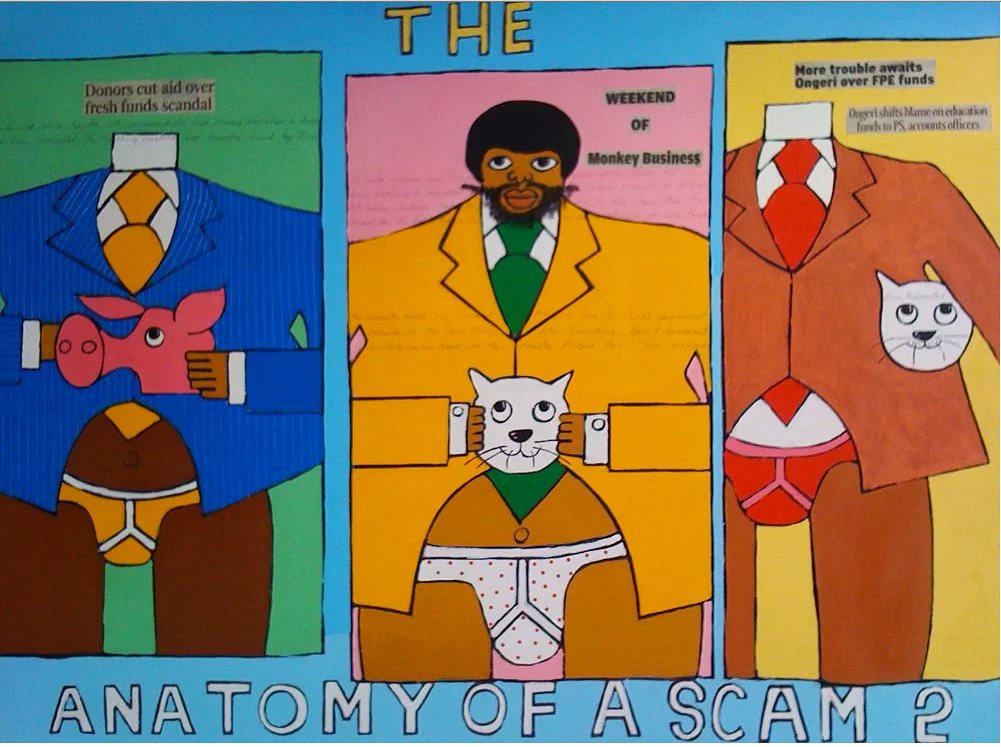

Working on an industrial estate, Michael Soi paints giant, brightly coloured pictures of bar-girls and international businessmen in Nairobi’s nightclubs, and talks of art as dissent. A mile or so away, Peterson Kamwathi stands in a cut-down shipping container cum studio and says it his role to fight polarisation. Next door, Longinos Nagila hangs a work bearing the slogan “The revolution will bring out the best of us” on a pigment-spattered wall.

All three are part of a new wave of politically engaged art fast emerging on Kenya’s burgeoning contemporary creative scene. Most are in their 20s or 30s, Soi’s 43, and their work reflects the frustrations of the vast but anonymous crowds in the east African nation, and across Africa, who are seeking new ways to challenge older leaders and elites in an often repressive and sometimes violent environment.

“They are young and angry and have seen injustice up close in a way which people in the west never do,” says Frank Whalley, a veteran art critic and journalist in Nairobi.

One international TV network recently dubbed the artists “provocateurs”, while the reaction of local media has veered between bemusement, shock and encouragement.

Though economic growth in Kenya is strong, the country has high unemployment, particularly among the young. Tens of millions of people go without basic services, while rule of law is patchy. Traffic chokes the pot-holed roads of the capital where high-rise office blocks and luxury hotels are built next to vast slums spilling over with those seeking escape from deep poverty in rural areas. Corruption is endemic. One whistleblower was shot dead last month, and police say they cannot find his murderers.

Photograph: http://kimaniwawanjiru.com

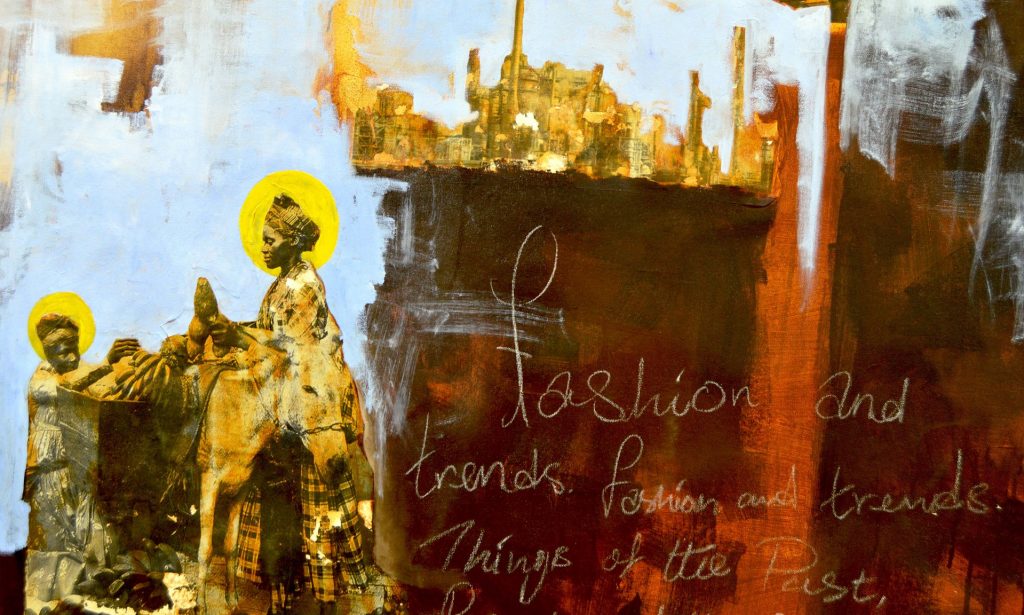

Soi’s work has made him one of the best-known local artists. His Fat Cat series clearly targeted those responsible for multimillion dollar scams in Kenya around a decade ago. A more recent painting dealt with the huge strain imposed on under-resourced police by politicians demanding protection for family members, or even lovers.

Soi has never been bothered by the authorities because, he believes, those in power in Kenya have never seen art as a threat.

“Art has always been seen as something for decorating homes and that is why we can get away with so much,” he says.

Elections in Kenya are still more than a year away but tensions are already rising. Demonstrations in recent months have turned into bloody street battles, with police beating and shooting opposition protesters. Though the most recent elections, in 2013, passed off peacefully there are widespread fears of a repeat of the violence that claimed the lives of 1,500 people in the aftermath of the disputed 2007 polls. Last week two people were killed in an ethnic clash on Kenya’s western border.

Whalley says art becomes important when it is difficult to directly criticise politicians.

“The democratic space is certainly opening [in Kenya] but as recent events showed the riot police are ever on standby. Direct action in the form of demonstrations continues of course but when the streets are closed political protest tends to surface in many other ways, one of which [is] through the countries’ artists.”

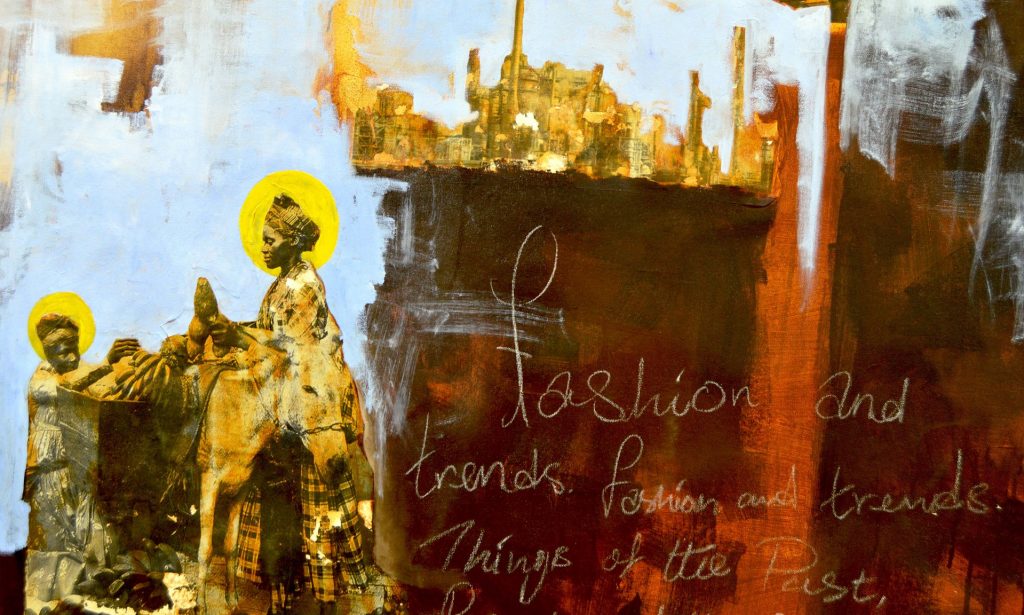

Some do not pull their punches – Nagila, who is 29, is working on an installation called Democracy My Piss – while others are more subtle.

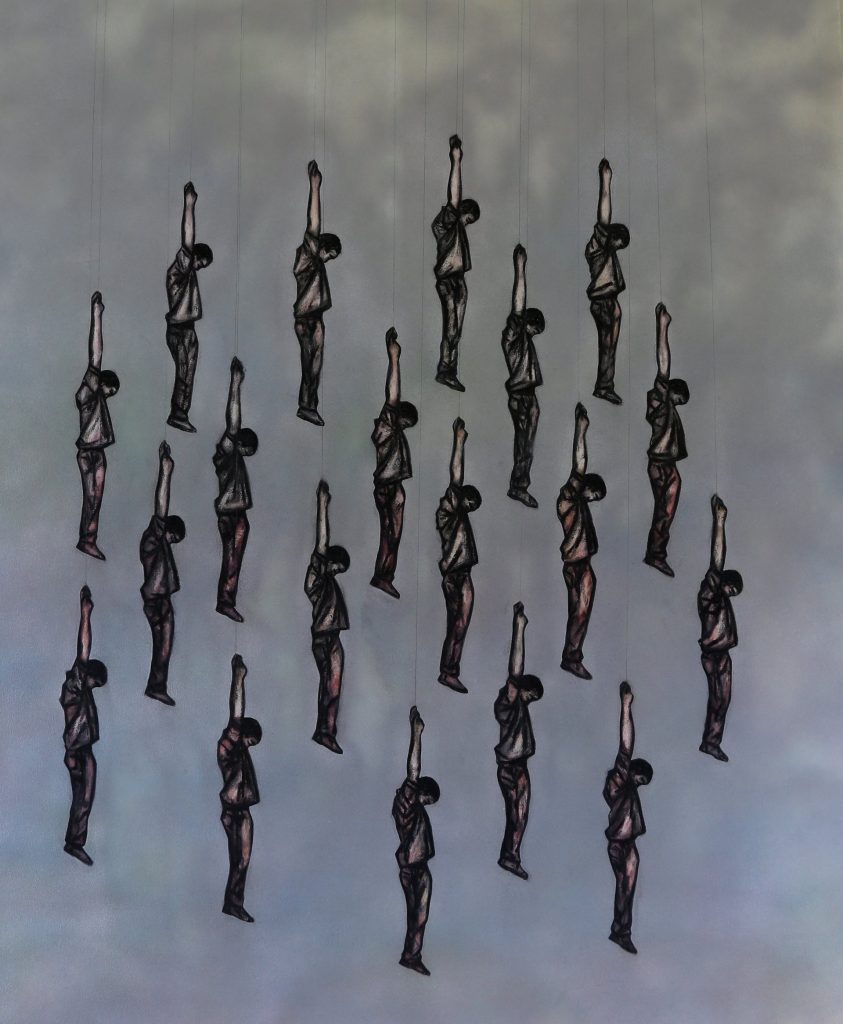

Photograph: Peterson Kamwathi

Kamwathi, one of the most acclaimed of the young Kenyan artists, gained international renown with a series of works which mercilessly portrayed those he blamed for the political instability and violence of recent years. A new show later this year focuses on immigration.

Kamwathi says he did “take sides”.

“I see myself as someone who creates a space for reflection. I don’t see myself as a political artist but then I cannot deny the reality that exists. Ultimately all artists react to the intensity of the context they are in and in Kenya politics permeates everything,” says the 36-year-old.

Some previously political artists have become more introspective. The most recent works of Boniface Maina, a young artist who has produced a series of political works in recent years, explore his recent depression.

But the impending elections has energised many others. Power in Kenya depends on sprawling and opaque networks of patronage while votes are often determined by tribal, ethnic and linguistic allegiance. President Uhuru Kenyatta and his deputy, William Ruto, are leading one coalition of communities. The vocal opposition represents others which feel marginalised. Analysts in Nairobi predict scattered but widespread violent incidences, but say catastrophic breakdown is very likely to be avoided.

Photograph: Saatchi Gallery

Anne Mwiti, who lectures in fine art at the Kenyatta University in Nairobi, won an award last year for work exploring ethnic identity and its role in the 2007-8 poll violence.

“It was very personal for me. I lived in a country that had been peaceful for a long time. The violence did not make sense,” she said.

Now the 45-year-old artist is planning a series of works to “reach out to the politicians, the stakeholders and all people to mobilise them against political violence and polarisation”.

Mwiti adds: “Right now, the tensions are having a direct effect on art. There is a general feeling that something [bad] is bound to happen. We want to use art in the public space to fight against that. We are hoping the young will say we don’t want violence and we want peace.”