Van Biak had only been away from her family in Leilet in north-west Myanmar for two weeks, but her mother was in tears as they embraced on the veranda.

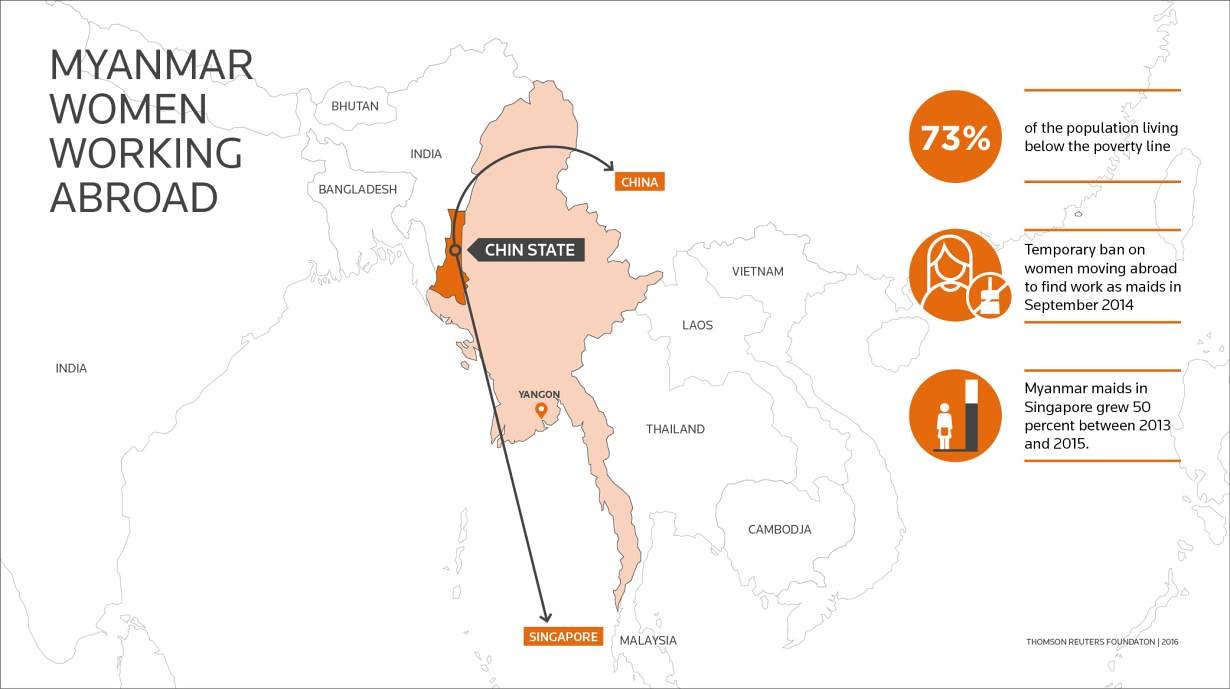

Biak and her older sister, Van Hnem, left to find work as maids in Singapore with few job opportunities in their remote village in Chin state, the poorest region of Myanmar where 73% of the population lives below the poverty line.

Biak and Hnem were aware of the risks. Another maid from Leilet has been working in Saudi Arabia for six years without pay or hope of return – and this was not an isolated case.

A number of high profile cases of worker abuse prompted the government in September 2014 to put a temporary ban on women going abroad to find work as maids.

But with few economic opportunities at home, the number of women leaving to get jobs abroad as domestic workers has not abated and more do so illegally, prompting calls for the newly appointed government of Aung San Suu Kyi to lift the ban.

“I’m ready to work hard and face difficulties abroad in order to help my family,” said Biak, who, at age 15, was too young to get a passport and so returned home.

Hnem, who is 18, made it to Singapore with six other girls from Leilet, lured by the chance to make up to $370 a month compared to Myanmar’s minimum wage of about $67.

Photograph: Katie Arnold/Thomson Reuters Foundation

“I am so scared they will be used as slave labour,” said her mother, a fear echoed by all parents whose daughters are now working abroad illegally.

For the ban has not only failed to stop women from Myanmar going abroad to work, but it has led to a black market that puts the women at greater risk of exploitation and slavery, according to the Humanitarian Organisation for Migration Economics (Home), set up to protect migrant workers’ rights in Singapore.

Since the ban was implemented, the fee paid by workers to secure a job abroad has increased to facilitate the bribes required to circumvent the ban. Workers do not see any money themselves until this debt is paid off.

Moreover, since these workers often leave their country as a tourist, they are not protected by labour or migration laws.

Jolovan Wham, executive director of Home, said the number of Myanmar maids in Singapore grew 50% between 2013 and 2015 with more than 30,000 now, which was evidence that the ban was not effective.

“Unfortunately, a lot of Singaporean employers request Myanmar maids because they are more affordable and generally more compliant,” Wham told the Thomson Reuters Foundation.

Sian Men Mawi legally worked as a maid in Singapore before moving to China, lured by the promise of a lucrative employment contract. She arrived in Guangzhou on a tourist visa.

Sian Men, 26, said she was enslaved by her agent who locked Myanmar girls in separate houses and rotated them through different jobs, holding their wages and never letting them pay off their debts.

“We didn’t know the agent would exploit another human being like that,” Sian Men said from her mother’s home in the Chin village of Zawgnte.

Sian Men managed to escape and returned to Myanmar by bus, evading the police who manned checkpoints along the route.

“We get into difficulty because of the agents but we can’t do anything about it because we don’t have legal passports or work permits. We have to do what the agency says,” she said.

The Thomson Reuters Foundation managed to get hold of Melody, Sian Men’s agent in Guangzhou, who admitted to enforcing a six-month debt bondage period but denied exploiting her employees.

“If their employer is unhappy then I have to replace them [before they pay off their bondage debts],” she said repeatedly, without giving her full name.

The Myanmar Overseas Employment Agencies Federation (MOEAF) said it has become harder for the authorities to police the movement of domestic workers across Myanmar’s borders because large employment agencies have been replaced by individual traffickers, often from within the victim’s social circles.

“It is particularly difficult to track the trafficking of girls from Chin and Kayin state because their church is often involved,” said Win Tun, vice chairman of MOEAF.

There were 130 official cases of trafficking in Myanmar last year, with a total of 641 victims. Chin state was the only region of Myanmar not to have recorded any official cases.

The anti-trafficking police division does not have a branch in Chin. The Thomson Reuters Foundation contacted the nearest office in Kalaymyo, Sagaing region, but it was unable to comment on the presence of trafficking in the neighbouring state.

In 2015, MOEAF signed a memorandum of understanding (MoU) with 12 employment agencies in Hong Kong who agreed to treat Myanmar staff according to the federation’s employment standards and it wants to see similar deals in other countries.

Photograph: Thomson Reuters Foundation

“These agreements would make it less dangerous for girls because we can ensure their labour rights are protected in their host countries, hold information about who is abroad and offer assistance to anyone that gets into trouble,” said Win Tun.

“But the last government didn’t want to know anything about them.”

MOEAF has met members of the new government twice since it took over in April. The department for labour declined to comment to the Thomson Reuters Foundation but a parliamentary committee is now considering whether to lift the ban.

“We are just waiting for permission from the new government, we are ready to sign MoUs with countries we know will offer good salaries and working conditions including Singapore, Hong Kong, Macau and Japan,” said Win Tun.

But until they do, campaigners fears thousands of women in Chin – and across Myanmar – will continue to seek employment as domestic workers through illegal channels, putting themselves at risk of slavery, trafficking and exploitation.

“When I am the right age, I will go again,” said Biak.