Not long after civil war began to ravage the Central African Republic in 2013, a fifth grade girl named Dorcas returned to her school hoping to see the familiar faces of teachers and friends. Instead, she encountered armed men who had taken over the school, ransacked it and burned benches and textbooks. “I burst into tears,” she said. “It took away my last hope.”

At a time when more than 30 countries around the world are officially experiencing humanitarian crises, including protracted crises, and more than half of the world’s out-of-school children live in countries plagued by war and violence, Dorcas’ words reflect the fear and desperation that all too many children face in the wake of natural disasters, major health emergencies and devastating armed conflicts.

The extraordinary scale of such suffering, now at its highest level since the second world war, has prompted world leaders to gather in Istanbul this week for the first-ever World Humanitarian Summit.

Beyond raising the visibility and sense of urgency around the growing challenges of conflict and crisis in nearly every region of the world, the Summit intends to improve the international community’s response to humanitarian emergencies.

A new education crisis fund

One important outcome of the Summit will be the creation of a new financing and coordination mechanism – Education Cannot Wait, an education crisis fund – to help children facing violence, displacement, epidemic, social breakdown, hunger and prolonged crisis get access to and stay in school.

We need this fund because global humanitarian responses have always given lower priority and fewer resources to education than to other essentials like basic health care, shelter and nutrition. Less than 2% of all humanitarian aid goes to education.

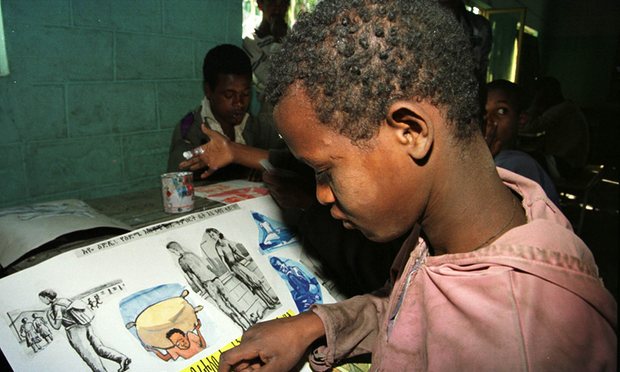

That’s shockingly low given that every child has a narrow, finite window of formative years during which they find it easiest to learn how to read, write and do math and acquire other cognitive skills. Formal schooling also helps shield children from the trauma of crisis.

What’s more, education is notably a powerful antidote to conflict. We know that literate people are more likely than others to participate in their societies’ democratic institutions and that the risk of war drops as more of a country’s citizens receive a secondary education. Further, once the urgent crisis subsides, how can a country expect to rebuild without a population that has even a basic of level of knowledge and literacy?

The new Education Cannot Wait fund is designed to mobilise additional funding, improve coordination and technical assistance and strengthen education sector planning and monitoring. It will also be an important tool to advocate for education to continue during emergencies and protracted crisis. It will allow more nimble and rapid responses to fast-moving emergencies and, at the same time, support long-term educational viability and growth.

Serving immediate and long-term needs

That’s precisely why the Global Partnership for Education (GPE) is playing a central role in the development and realisation of the new education crisis fund. Based on its strong partnership model, GPE expedites support when developing countries experience a sudden or prolonged crisis and helps them transition to long-term development. GPE does this by providing the support needed to build durable, quality education systems.

In the Central African Republic, for example, GPE quickly approved emergency support to allow more than 100,000 children who had been displaced by conflict to return to school, helped rehabilitate hundreds of school buildings and promoted teacher recruitment and training and other efforts to rebuild the country’s crumbling education system.

In Chad, a GPE-funded emergency program has enabled the government to shore up an already over-burdened school system to serve thousands of refugee children who have fled violence in neighbouring countries.

In South Sudan, which has been torn apart by civil war, partners like GPE have helped the government create and execute a plan to improve the national education system, assist schools in improving their performance, offer models for school strengthening and enable more girls to receive an education.

In each of these countries, and many others facing crisis, this immediate support feeds into a broader, longer-term vision to educate all children, particularly girls and other disadvantaged children who are the hardest to reach.

The solutions we hope to achieve at the World Humanitarian Summit – above all, elevating education as an essential part of any humanitarian response – won’t completely extinguish all the challenges children face during humanitarian crises. But they will rescue millions from likely lives of misery, poverty and tragedy.

By taking firm and bold steps, the international community can restore their last, and indeed best, hope to improve their lives long after crises subside.

One Response

Very interesting development, I hope the GPE effort can be stretched to also reach the northern part of Nigeria. Several children in the north are still without basic primary education