The rumour was there would be chicken.

Word had spread that a delivery of poultry meat was due at the Central Madeirense supermarket, and long before dawn a queue of shoppers was snaking around the block.

Kattya Alonzo was one of them. The 48-year-old mother of three was already planning to make the traditional chicken and rice dish arroz con pollo – if she could also find some rice.

“I haven’t been able to buy chicken in more than a month, so I was there early at about 4am,” she said.

At about 6.30, two trucks finally drew up outside the store, but before the drivers could start to unload, national guardsmen told them to drive on.

Venezuela is rich in oil, but dogged by chronic shortages of basic goods and essential medicines, electricity and water rationing, spiraling inflation and rampant crime.

Perhaps it was not surprising that the mood outside the supermarket quickly turned ugly: frustration turned to despair, anger to violence. Before long, the incident on Tuesday had escalated.

Mobs tried to loot several bakeries and delis and another food delivery truck.

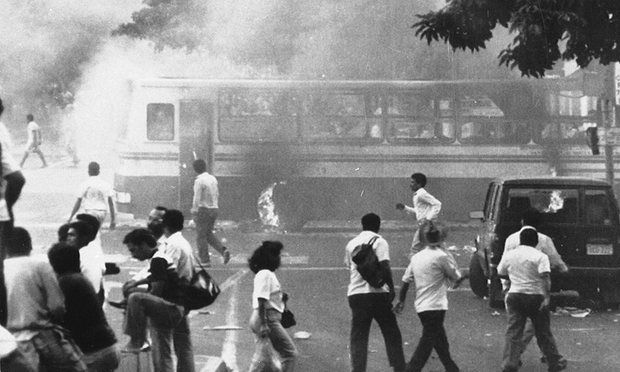

The unrest soon spread throughout this city of 200,000 just outside the capital, Caracas. Protesters shouted “We want food” as they blocked intersections with burning tyres and clashed with security forces.

Police and the national guard quickly controlled the outburst, with some 14 people reportedly arrested, and at least one person was injured, according to witnesses.

The protests were not related to marches in Caracas and other major cities, which were called this week by opposition leaders seeking to cut short the term of President Nicolás Maduro who they say has driven the country into the ground through mismanagement.

But spontaneous outbursts such as the one in Guarenas may present a more serious challenge to Maduro’s rule than any efforts by his political rivals.

The opposition won control of parliament in December elections, but Maduro has blocked all attempts at reforms passed in the legislature though the government-controlled supreme court.

Maduro blames the country’s woes on an “economic war” against his government by rightwingers and foreign interests. Last week Maduro decreed a 60-day state of emergency because of the “threat” against his government.

Maduro has described the referendum push as an attempt to justify a coup d’état or a foreign intervention, and on Friday the Venezuelan armed forces began two days of military exercises as show of force in the face of such threats.

But as the events in Guarenas show, the country is on a knife-edge.

Venezuelans have been living with shortages of food and essential items for nearly three years as the oil-dependent economy began to buckle. And patience is wearing thin.

The Venezuelan Observatory of Social Conflict registered 2,138 protests between January and April, most of them spontaneous manifestations of anger or frustration. Incidents of looting have nearly quadrupled in the same time.

“We are like a bomb going tick-tock, tick-tock,” said Zenovia Villegas, a 54-year-old housewife who waited in line at a Guarenas supermarket since the early hours of Thursday only to be told at 3pm that the store would not be opening its doors that day. Dejected, she went home empty-handed.

Authorities have reason to be nervous of unstructured shows of dissent, particularly in protest-prone Guarenas.

It was in here that protests in 1989 against neoliberal reforms and a hike in bus fares sparked a wave of looting and violence that came to be known as the “Caracazo” in which as many as 3,000 people died.

Those events are said to be what motivated an attempted coup in 1992 by an army lieutenant-colonel named Hugo Chávez who would later become president and set the country on a “revolutionary” path under the banner of 21st-century socialism.

At the entrance to Guarenas a sign boasts that the city was the “birthplace of the revolution”.

The charismatic and wily Chávez, who led the country from 1998 till his death in 2013, enjoyed unprecedented support for his oil-funded social programs that brought health services, education and housing to poor Venezuelans.

Maduro, his successor, has not managed to win the same levels of popular support and as oil prices dropped the country’s economy has gone into a tailspin.

An opposition coalition, known as MUD, is trying to force a recall referendum on Maduro, which would cut his six-year presidential term in half. They have collected the first batch of signatures to begin the process but accuse electoral authorities of stalling in processing them.

But for people on the street that’s just politics.

“We don’t care who’s in Miraflores,” said Marlene Pineda who runs a newsstand in Caracas, referring to the presidential palace. “What we want is food,” she says reflecting the sentiment of many Venezuelans far removed from politics who are struggling to get by day to day.

“Food is what moves people,” says Carlos Perdomo, who sells unrefined sugarloaves known as papelón in an area called Samán where protesters congregated on Tuesday.

But so does the feeling of impotence. A rash of mob justice has gripped Venezuela as violent crime soars with little response from security forces.

In the Mesuca neighbourhood of Caracas – considered the most dangerous area of the world’s most murderous city – motorcycle taxi drivers swap horror stories as they nervously wait for fares.

Accepting the wrong fare may cost any one of them their motorbike or their life.

“When a passenger comes the first thing we do is look at their waist” for any sign of a gun, said Carlos Paredes. “For us, going to work is like a lottery.”

Impunity is so widespread that lynchings have now become common.

Several months ago a thief stole a motorcycle at gunpoint in one of the steep winding streets of the neighbourhood. A group of motorcyclists chased down the thief, beat him, doused him with gasoline and set him on fire.

John Díaz, 25 said he didn’t participate in the mob but saw the man’s charred remains on the street.

“People are fed up. With everything,” he said.

The lynching and looting are manifestations of anger and impotence that clinical psychologist Liliana Castiglione is seeing in her practice where 80% her patients’ problems are related to the country’s economic and social crisis.

“People are desperate, they are depressed and they’re angry,” said Castiglione, who launched a blog called Psicólogas al Rescate (Psychologists to the Rescue) where she and partner Stefania Aguzzi offer low-cost or sometimes free consultations for Venezuelans struggling to cope.

“One woman this week told me straight out that she wanted to kill people,” said Castiglione. “Like many Venezuelans she feels trapped.”

One way to channel that frustration is by standing up and expressing through protests, Castiglione said, but security forces are quick to stifle them.

At the time of the Caracazo, police and soldiers at first stood by when the looting and protests started. Today security forces are under orders to quell any sign of protest immediately.

Several days after the unrest in Guarenas, the city remained tense. Groups of national guardsmen in riot gear watched over a busy informal street market to prevent any further turbulence.

“If you complain too loudly, they arrest you,” says María David, a 71-year-old retired nurse. “As soon as people protest, the military is there.”

“That’s the reason things haven’t blown over, yet,” she says. “Fear.”