Mardoche was 11 when I first met him, shivering in the corner of a youth psychiatric ward in Chelsea.

Before I could speak, he looked up. ‘I am not a witch,’ he said. ‘I don’t even know what this kindoki [witchcraft] is.’

This wasn’t my first encounter with a sinister phenomenon taking hold across Europe and Britain.

‘Witch branding’– telling a child they’re possessed by witchcraft and face life-threatening exorcism – is already an epidemic in Africa.

Today there are hundreds of cases of witch branding in Britain, perhaps thousands.

Most involve people from Africa, where traditional beliefs in black magic are widespread.

Others involve Muslims who believe in ‘jinns’ or spirits, an element of Islamic theology.

The children are ‘cured’ with the utmost brutality: starvation, violence, sometimes torture, and in a number of appalling cases, death. As I know only too well.

I am a regular expert witness in the courts.

I am the only multicultural expert on the national police database and I know the trafficking of foreign children into Britain is getting worse.

Yet, content in our own well-meaning attitudes, we are doing nothing in response.

In fact we are complicit.

Dr Richard Hoskins (right) has been assisting Mardoche Yembi (left) after his experiences involving exorcism. Kristy Bamu, 15, was found dead in an East London high-rise in 2010.

We are helping its spread through our porous borders, the weaknesses of our welfare state, and the hapless political correctness of our police and social services.

They live in thrall to the mantra that children are always best off cared for in their own racial community – even if that community is doing them harm.

Mardoche came to London from the Democratic Republic of the Congo as a toddler.

When he was about eight, his relatives accused him of being a witch.

Traumatised, he started struggling at school. Islington Social Services heard his family wished to return him to the Congo for an exorcism – or deliverance – ceremony.

This would cleanse him, they said, of the witchcraft, known in the local lingala language as kindoki.

Mardoche’s representative, Sarah Beskine, persuaded the judge I should be instructed.

I asked Islington Council if they would co-fund my trip to Africa to investigate.

To my astonishment, they funded half my costs to the tune of £2,200, although a council source informed me there was disquiet about a white person being instructed on a ‘black case’.

I went to the Congo in 2005 and spent a fortnight with Mardoche’s extended family. I interviewed them and spoke with the pastors who would conduct the exorcism.

In Kinshasa, I witnessed the exorcism of another young boy of Mardoche’s age.

His mouth was parched and he was close to fainting.

Prior to exorcism, a child is not allowed to eat or drink for several days.

I’ve since seen children on the point of death after being fasted.

Over the next two hours, the boy was forced to stand upright while a dozen adults shouted and screamed.

Eventually, exhausted, he was bent double, vomiting on to the dusty floor where he passed out. ‘See,’ a rotund pastor beamed at me. ‘The witchcraft just left him.’

Back in the UK, I told the court that sending Mardoche to the Congo for exorcism would place his life in grave danger.

The judge ordered he should be taken into foster care.

When I tried to question Islington Council, it clammed up. Why did they consider letting a child in their care be sent back to Africa for exorcism?

Who thought political correctness came above child protection? Every question was met by resistance.

They hid behind the Family Court and threatened me with contempt proceedings. They didn’t want Mardoche’s story to be known.

It is a story that recurs with alarming regularity.

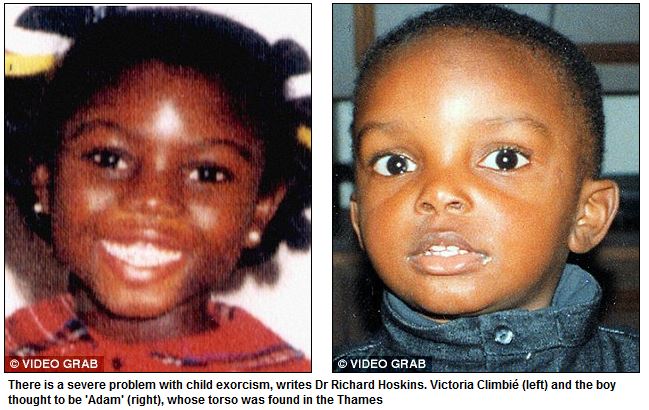

Victoria Climbié was eight when she was tortured and killed by her ‘aunt’ Marie-Thérèse Kaou and partner Carl Manning in February 2000. They thought she was a witch.

The infamous cases of the eight-year-old Angolan orphan known as Child B and ‘the torso in the Thames’ – named ‘Adam’ by police and identified as a victim of ritual abuse and murder in my book, The Boy In The River – were also linked to accusations of witchcraft.

However, hundreds of cases go unreported thanks to the secrecy of family courts and local authorities.

Newham Council tried to prevent you ever knowing about the murder of 15-year-old Kristy Bamu, who was found dead in the bath of a bleak East London high-rise on Christmas Day 2010.

If I hadn’t fought their gagging order at the Royal Courts of Justice, they’d have succeeded.

Kristy had been tortured for five days and suffered 101 injuries because his eldest sister, Magalie Bamu, and her boyfriend, Eric Bikubi, thought he was a witch.

These cases are the tip of the iceberg.

One Response

This issue of witchcraft and its exorcism is prevalent in the southern part of Nigeria. Especially in Cross river & Awka ibom. Children are maimed and even burnt during this so called exorcism. I’d like to ask a question to my Christian folks here. Is exorcism scriptural? Because tthese pastors that carry this actions believe they are doing the right thing.