How about this for a stark indication of growing income inequality: The rich can now expect to live 15 years longer than the poor.

That’s the main conclusion of a major new analysis of income patterns and life expectancy that shows a widening “life expectancy gap” between income groups.

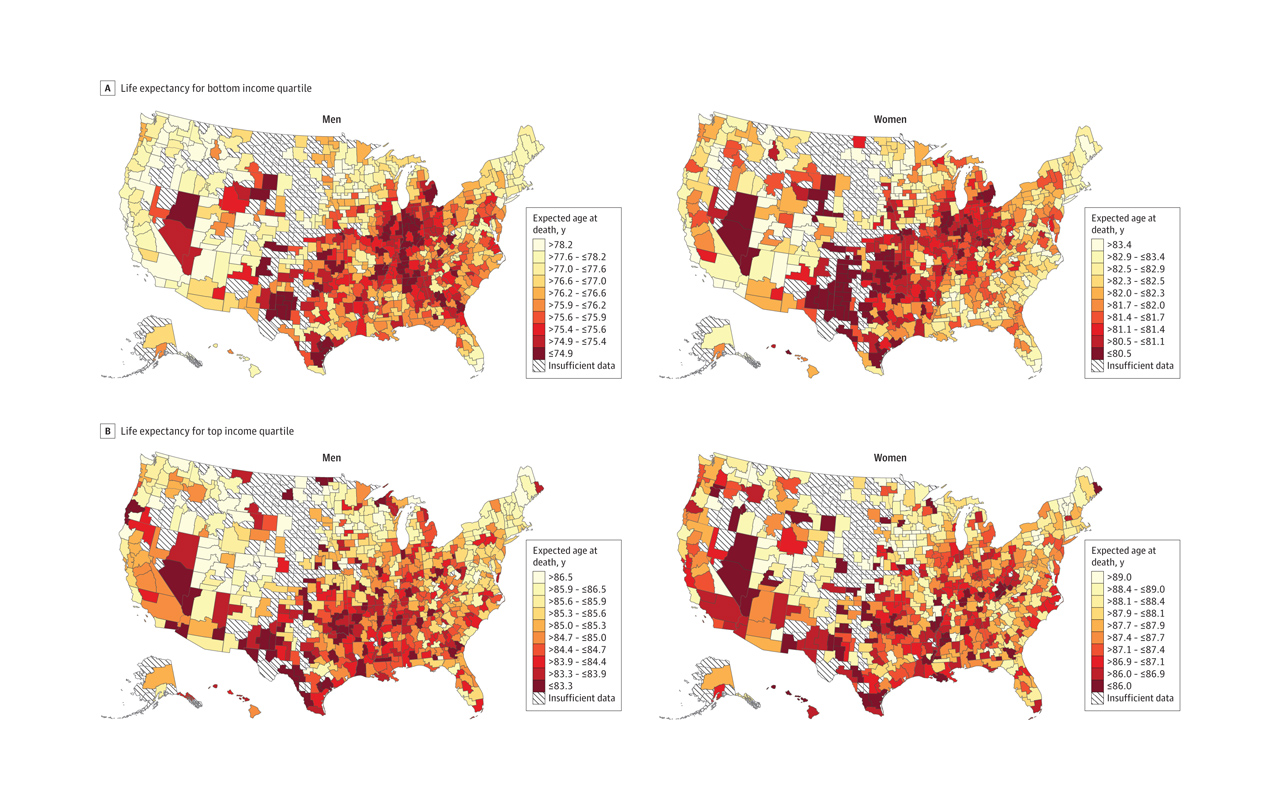

But here’s a somewhat happier piece of information contained in the same research: Among the poorest Americans, lifespan varies significantly depending on where people call home. The bottom-1% live almost five years longer in New York than Oklahoma, suggesting the importance, and promise, of local interventions to improve health.

The research, led by Stanford economist Raj Chetty, is based on 1.4 billion anonymized tax records filed from 1999 to 2014. It estimates life expectancy for individuals aged 40, adjusting for race and ethnicity.

Top-1% men stand to live 14.6 years longer than bottom-1% men; among women, the gap is 10.1 years. And, what’s more, the gap between income groups is growing. Among the top-5%, life expectancy grew 2.34 years for men and 2.91 years for women between 2001 and 2014, but, among the bottom-5%, it grew only 0.32 years for men and 0.04 years for women.

However, trends at the bottom end of incomes varied by up to 4.5 years depending on the location. For example, New Yorkers in the bottom quarter of incomes can expect to live to 82 years old, while the same group in Gary, Indiana can expect to live only to 77 years—a statistically significant difference. Among the top quarter, the geographic differences aren’t so wide, ranging from Salt Lake City at the high end of longevity (88 years) to 84 years in Nevada.

The research adds weight to the idea that health is local (as many health campaigners have been saying) and not necessarily tied to health care availability. Whether someone smokes may be as important as whether they have health insurance. “Geographic differences in life expectancy for individuals in the lowest income quartile were significantly correlated with health behaviors such as smoking, but were not significantly correlated with access to medical care,” the paper, published in the Journal of the American Medical Association, says.

The research suggests focusing on a local level to improve health, intervening among low-income groups in places like Las Vegas, Tulsa, and Oklahoma City where life expectancy is lowest. Still, the geographic differences between people are less wide than the differences related to income. The big story here is about the divergent effects of income inequality, not the lifespan gaps between poor people living in different places.