At M.I.T.’s Media Lab, the digital futurist playground, David Rose is investigating swaddling, bedtime stories and hammocks, as well as lavender oil and cocoons. Mr. Rose, a researcher, an inventor-entrepreneur and the author of “Enchanted Objects: Design, Human Desire and the Internet of Things,” and his colleagues have been road-testing weighted blankets to induce a swaddling sensation and listening to recordings of Icelandic fairy tales — all research into an ideal sleep environment that may culminate in a nap pod, or, as he said, “some new furniture form.”

At M.I.T.’s Media Lab, the digital futurist playground, David Rose is investigating swaddling, bedtime stories and hammocks, as well as lavender oil and cocoons. Mr. Rose, a researcher, an inventor-entrepreneur and the author of “Enchanted Objects: Design, Human Desire and the Internet of Things,” and his colleagues have been road-testing weighted blankets to induce a swaddling sensation and listening to recordings of Icelandic fairy tales — all research into an ideal sleep environment that may culminate in a nap pod, or, as he said, “some new furniture form.”

“For me, it’s a swinging bed on a screened porch in northwestern Wisconsin,” he said. “You can hear the loons and the wind through the fir trees, and there’s the weight of 10 blankets on top of me because it’s a cold night. We’re trying a bunch of interventions.”

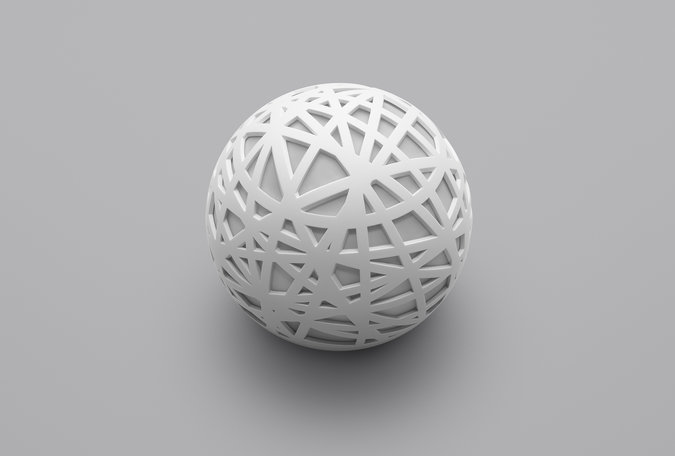

Meanwhile, at the University of California, Berkeley, Matthew P. Walker, a professor of neuroscience and psychology and the director of the Sleep and Neuroimaging Laboratory there, is working on direct current stimulation as a cure for sleeplessness in the aging brain. Dr. Walker is also sifting through the millions of hours of human sleep data he has received from Sense, a delicately lovely polycarbonate globe designed to look like the National Stadium in Beijing that measures air quality and other intangibles in your bedroom, then suggests tweaks to help you sleep better.

“I’ve got a mission,” he said. “I want to reunite humanity with the sleep it is so bereft of.” Sense is the first product made by Hello Inc., a technology company started by James Proud, a British entrepreneur, for which Dr. Walker is the chief scientist.

Sense, a delicately lovely polycarbonate globe designed to look like the National Stadium in Beijing that measures air quality and other intangibles in your bedroom, and then suggests tweaks to help you sleep better.

Sleep entrepreneurs from Silicon Valley and beyond have poured into the sleep space, as branders like to say — a $32 billion market in 2012 — formerly inhabited by old-style mattress and pharmaceutical companies.

“I can see sleep being another weapon in competitive parenting and career-building,” Ms. Salzman said. “If you want your child to succeed, do you have to buy them these sleep devices? Sleep is personal, it’s class, not mass, and now the sleep industry is based on technical services, customized for me. It’s a bizarre marriage of high tech and low tech. Chamomile tea is going to have a resurgence, as the antithesis to the whole pharma thing.”

The familiar paradigm of success used to center on the narrative of the short sleeper: Corporate titans and world leaders — like Martha Stewart and our last two presidents — counted abbreviated rest as proof of their prowess. It turns out that short sleepers, as they are known, may have a genetic mutation, as Arianna Huffington pointed out in her 2016 book, “The Sleep Revolution: Transforming Your Life One Night at a Time.”

(It’s worth noting that George W. Bush, formerly a sleep outlier among his presidential peers for clocking in around nine hours of nightly shut-eye, along with a daily nap, is newly popular.)

The Army has proclaimed sleep a pillar of peak soldier performance. Jeff Bezos, the chief executive of Amazon, who used to take a sleeping bag to work when he was a lowly computer programmer, has said that his eight hours of sleep each night were good for his stockholders. Ms. Huffington’s new company, Thrive Global, whose first-round investors include the internet entrepreneur Sean Parker and the venture capital firm Greycroft Partners, is working with Accenture, JP Morgan Chase and Uber, among other companies, on antiburnout programming, which educates their employees on the importance of sleep. Aetna, the health care company, is paying its workers up to $500 a year if they can prove they have slept for seven hours or more for 20 days in a row.

But the growing pile of apps, gizmos and gurus — some from unlikely corners — has led to “pandemonium in the bedroom,” Ms. Rothstein said.

In 2015, the actor Jeff Bridges made a spoken-word album, “Dreaming With Jeff,” a project for Squarespace, that reached No. 2 on Billboard’s New Age chart and raised $280,000 for the No Kid Hungry campaign, for which he is the national spokesman. He collaborated with Keefus Ciancia, the composer and music producer, on a truly weird collection of quasi-bedtime stories, musings about death and also a humming song, with Mr. Bridges’s familiar gruff voice and all manner of ambient sounds that many listeners found more alarming than sleep-inducing.

“I don’t know where this is leading,” Mr. Bridges said the other day, “but I’m steeping myself in the subject. We’re working on something called Sleep Club, which will be sort of a hub for all things sleep related.”

“Dreaming With Jeff” made me anxious, as did “Sleep With Me,” a podcast by Drew Ackerman, a gravelly voiced librarian in San Francisco, whose “boring bedtime stories” are designed to cure insomnia and are downloaded at a rate of 1.3 million a month, as The New Yorker reported last year. I’m more drawn to the thousands of “songs” in Spotify’s Sleep Sound Library, particularly “full gutters” and “office air-conditioners,” and I have a white noise machine. But recently, desperately, I craved a more substantial intervention, perhaps a cure for the 3 a.m. fretting that has plagued me for years.

Mr. Mercier sent me his Dreem headset, a weighty crown of rubber and wire that he warned would be a tad uncomfortable. The finished product, about $400, he said, will be much lighter and slimmer. But it wasn’t the heft of the thing that had me pulling it off each night. It skeeved me out that it was reading — and interfering with — my brain waves, a process I would rather not outsource.

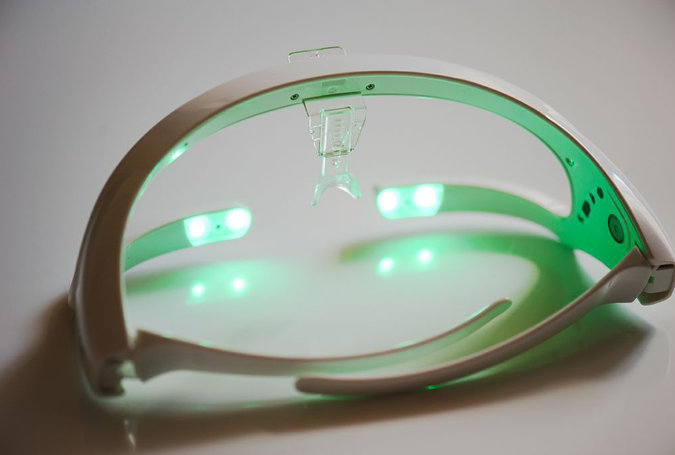

I was just as wary of the Re-Timer goggles, $299, which make for a goofy/spooky selfie in a darkened room. My eye sockets glowed a deep fluorescent green, and terrified the cat.

The Ghost Pillow, $85, has “patent-pending thermo-sensitivity technology” designed to keep your head cool. It is wildly comfy, but when I read what it is made from, a polyurethane foam, I lost sleep. I bought a Good Night Light LED Sleep bulb, $28, which comes with its own “patented technology” to support your body’s melatonin production. I can’t tell if that’s what happened, but since the bulb is too dim for my middle-aged eyes, I struggled to read my go-to sleep aid, a worn copy of “The Pursuit of Love,” by Nancy Mitford, and knocked off a good half-hour earlier than usual. I was up again at 3 a.m., however, as my new Sense pod alerted me the next day, through an app on my phone. And again at 5 a.m., when the cat swatted the pod off the night stand and it glowed red in protest. “There was a noise disturbance,” the app explained.

My so-called sleep summary, as provided by Sense, was both compelling and off-putting. Why is my air quality “not ideal”? And how comfortable am I sharing my sleep habits with a Silicon Valley start-up?

Ms. Rothstein, the sleep ambassador, is less bothered by privacy concerns than by the temptation to wakefulness that phone interfaces pose. And nearly every gizmo seemed to have one.

“I’d like to have a survey done to show how many people are also reading their texts while they’re tracking their sleep,” Ms. Rothstein said. “If you want to improve your sleep, you have to make some changes. Your Fitbit and your Apple Watch are not going to do it for you. We’ve lost the simplicity of sleep. All this writing, all these websites, all this stuff. I’m thinking, Just sleep. I want to say: ‘Shh. Make it dark, quiet and cool. Take a bath.’”

Ms. Rothstein taught me her relaxation recipe, a practice that mixed gratitude with body awareness and breathing. Start with your toes, she said, and thank your body parts for their hard work. (My favorite: “Knees, I know it’s not always easy for you. You can rest now.”)

Still, the best sleep I’ve had in weeks cost $22, and lasted 33 minutes. It was a Deep Rest “class” at Inscape, a meditation studio in the Chelsea neighborhood of Manhattan designed by Winka Dubbeldam, the sought-after Dutch architect, to evoke the temple at Burning Man, and other esoteric spaces, and created by Khajak Keledjian, a founder, with his brother, Haro, of Intermix, which they sold to the Gap for $130 million in 2013.

Mr. Keledjian, a meditator, aims to make the practice both secular and modern: a “mindful luxury,” he said. Though there are human “facilitators” in each class, who gently touch the feet of snoring attendees if they get too loud, the practice is guided by a recording made by an Australian female member of Mr. Keledjian’s company. “We call her ‘Skye,’” he said. It was lunchtime on a rainy Tuesday, and I settled onto a soft mat outfitted with a bolster, a pillow and a cozy fleece blanket. “Skye” urged me to stay awake, and then delivered a script like Ms. Rothstein’s, in mellifluous antipodean tones. I drifted once or twice, and from the muffled snorts of the other attendees, they did too. That night, I slept until dawn.