Photograph: Alamy Stock Photo

Two months ago on Tuesday, Britain voted to leave the European Union. The shock was immense; the fallout dramatic. But then summer came. The early turbulence subsided and normality (more or less) returned.

Brexit, though, has not yet begun to happen.

The government does not know what it wants and is not yet equipped to ask for it. Britain and the EU, it is increasingly clear, are far more intimately enmeshed than the leave camp had claimed. For all the leavers’ assurances, extricating the UK from the bloc, negotiating new relationships with Europe and the rest of the world – and ensuring that Britain’s laws and practices adapt – is a gargantuan undertakin

g.

The referendum result, however, is a political reality. The 52% of leave voters – and the politicians who represented them – expect it to be acted upon. So two months on, where does Brexit stand?

The machinery – and the cost

One of the first acts of the new prime minister, Theresa May, was to establish two new ministries: the Departments for Exiting the European Union, led by David Davis, and for International Trade, headed by Liam Fox.

Neither is yet fully up and running. Worse, a predictable and potentially damaging turf war already appears to be under way between Fox’s ministry and the last of the cabinet’s three Brexiteers, Boris Johnson at the Foreign Office. That aside, International Trade has so far secured about 10% of the trade negotiators it needs. (Britain has few skilled personnel because the EU negotiates trade deals for its members. Canada, in contrast, has 300.)

Meanwhile, DExEU, as it is known, has hired – mainly from elsewhere in the civil service – 150 of the 250-300 total staff it is expected to employ, and reportedly has yet to move into its permanent home. Some meetings still take place in Starbucks on Victoria Street, London. With the civil service a fifth smaller since 2010, fast-stream recruits are being drafted in, but negotiators, lawyers, economists, regulatory experts and management consultants from the private sector will prove essential.

They will not come cheap: experienced senior personnel from the likes of KPMG, PwC, Linklater’s and McKinsey cost up to £5,000 a day, recruitment consultants say, or will be seconded on annual salaries of up to £250,000.

Photograph: Denis Balibouse/REUTERS

Some estimates suggest “full Brexit” may take 10 years and involve up to 10,000 people, not only in the new and other so-called “hot” departments such as foreign, home, environment and business, but across the civil service nationally, at an administrative cost of close to £5bn.

Hannah White, Brexit lead at the Institute for Government, claims such figures are “finger in the wind” stuff, but warns that with all the government has set out to achieve besides Brexit, “There is clearly going to have to be a really, really strong process of prioritisation.”

The model – and why it matters

The government has not yet decided what trade relationship it wants with the EU. A huge amount hangs on the choice between “membership of” and “access to” the EU’s single market.

European leaders have repeatedly stressed that membership of the single market as part of the European Economic Area (like, say, Norway) will mean accepting EU immigration, obeying EU rules and making a contribution to the EU budget. Single market membership would make Brexit a lot easier to implement and could – according to the Institute for Fiscal Studies – be worth roughly 4% to the UK’s GDP. It is, however, unacceptable to many leave voters.

One alternative is a free trade agreement with the EU giving Britain access to the single market on improved World Trade Organisation tariffs, such as Canada’s recent deal. Although that may be politically acceptable it would take longer to agree and could hit the economy harder – especially the all-important services sector; trade deals are invariably much tougher on services than on goods.

Recent signs indicate the government may be mulling a deal outside the single market as the only option acceptable to voters. May has spoken of a “bespoke” agreement, and ITV’s Robert Peston reckons Whitehall is aiming for a deal based on Canada’s, albeit with “a bespoke add-on for services”.

The City reportedly wants an arrangement along the lines of the complex patchwork of bilateral sectoral accords Switzerland has agreed with the EU for access to parts of the single market – though the Swiss, problematically, had to accept freedom of movement and EU regulations as part of their deal.

Before any decision can be made, DExEU has to work out exactly which bits of single market membership – including non-tariff barriers, the common regulations, licences and standards that, for example, give UK banks their “passport” to operate across the EU – are most valuable, and what they are worth.

The politics – and the timing

Theresa May’s catchphrase that “Brexit means Brexit” may disguise Whitehall’s uncertainty about what Brexit actually means, but it does commit to deliver it – and there are plenty pushing to ensure it does.

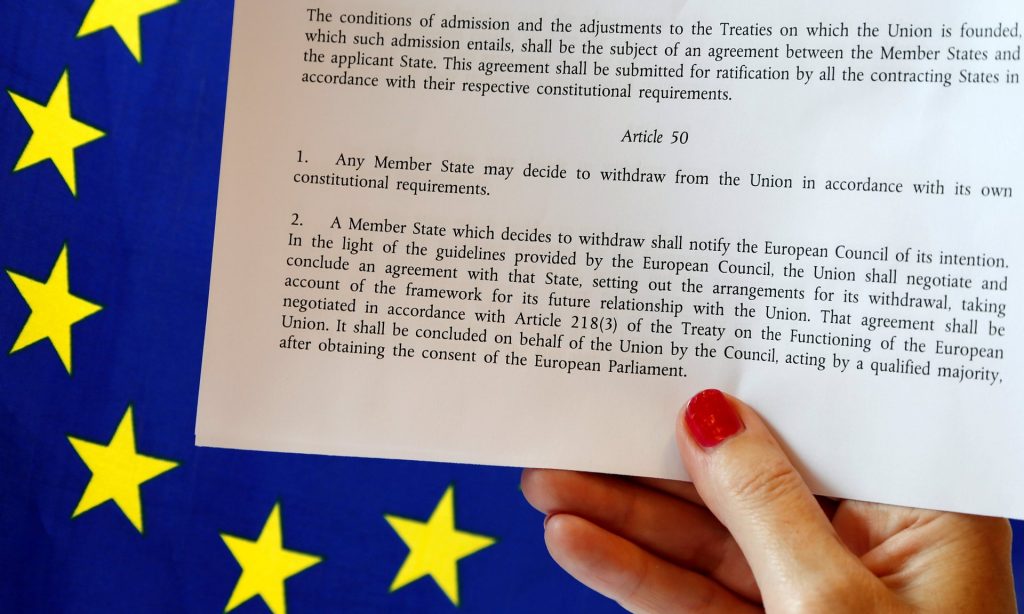

Former Ukip leader Nigel Farage has threatened to return to the fray if nothing happens soon and there are many within May’s own party and the broader leave camp who believe all Brexit requires is for Article 50 of the Lisbon treaty to be triggered and a short Act of Parliament to be passed.

That constitutes a “hard” Brexit: crashing out of the EU and the single market with no economic safety net beyond WTO rules, which would mean costly tariffs. The “soft” approach – taking time to negotiate an exit and a preferential trade arrangement – is plainly the government’s favoured course.

May has repeatedly said she would not trigger Article 50, the two-year process by which Britain must leave the EU, before the beginning of next year. Some think March looks a likely moment.

Photograph: Francois Lenoir/Reuters

But there is a persistent rumour that late 2017 or even early 2018 is more likely, partly because it could take Whitehall at least that long to be ready before triggering the two-year exit talks, and partly because Dutch, French and German elections will get in the way.

That would mean Britain would not leave the EU until late 2019, which the pro-Brexit camp – as well as the EU, who want Brexit over before the 2019 European elections and the new EU budget in 2020 – have said emphaticallyis not desirable.

Some observers argue that since the Tory leadership has never been capable of resisting its Eurosceptic wing (of which Davis and Fox – the day-to-day Brexit ministers – are hardcore members), the talks may prove short-lived: a “hard” Brexit could happen.

Those other negotiations …

Assuming Brexit remains soft, Article 50 is just the beginning, covering the essential details of the divorce: who pays the pensions of Britain’s EU staff, where the EU institutions based in Britain end up.

As well as the Article 50 talks must follow a raft of others, including Britain’s new trade deal with the EU, which could prove so complicated it requires an interim agreement to tide things over.

Then Britain’s full WTO membership must be re-established (which means drawing up a new set of national tariffs, a monumental task, and winning approval from 164 countries), and the 50-plus free trade agreements negotiated by the EU on its members’ behalf re-signed.

Photograph: Alamy

Plus, as Charles Grant of the Centre for European Reform points out, new deals will be needed on European security, defence, the environment, science and research and, in all probability, Northern Ireland.

And that takes no account of the changes needed in UK domestic laws and regulations. Brexit, notes Dominic Cook of Oxford University’s Saïd Business School, is “the biggest transformational project a UK government has ever undertaken” not only because of foreign negotiations but “the inward-facing part: implementing and educating in the UK”.

The legal challenges

The most immediate obstacle to Brexit is judicial. There is a substantial school of thought which says the government is not constitutionally entitled to pull the trigger on Article 50 without the specific approval of parliament.

At least seven private actions have been grouped together and will be heard by the high court starting in October in what judges have said is a “matter of great constitutional importance”, with a decision possible by the end of the year.

Separately, cases have been launched in Northern Ireland arguing that Brexit would breach the Good Friday agreement by reinstating a physical border with the Republic of Ireland and undermining the legal basis for the 1998 peace deal.

So, while we may be two months in, you might want to get used to the waiting. Brexit may not happen quite yet.