The launch of yet another state-run social media site in Uzbekistan has highlighted the government’s contradictory attempts to control the internet.

From just 7,500 internet users in 2000, online access as soared in the last 15 years, with current estimates suggesting 12.7 million people in the country are now online.

But while the government has been largely supportive of this growth, it continues to be highly suspicious of social media.

Market researchers J’son & Partners estimated that the number of social network users in Uzbekistan grew by 40% per year between 2010 and 2014, the highest rate in the entire post-Soviet world.

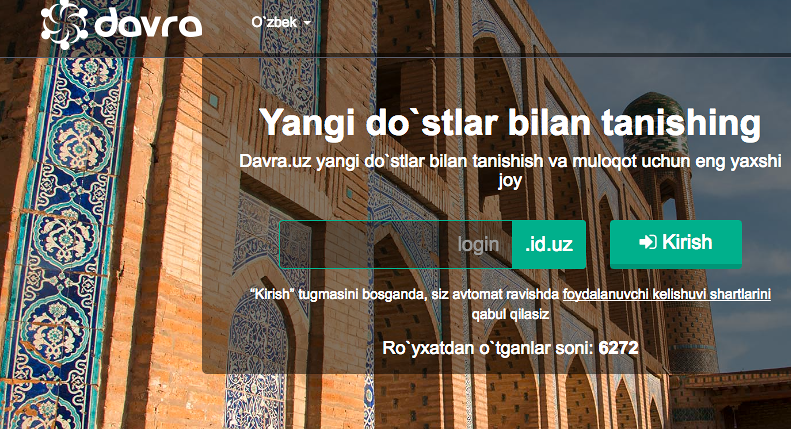

In response, the government has created no less than 38 of its own networking sites, although only eight of them are currently operational. The latest addition is Davra.uz, officially launched on 1 June .

Built by a state-owned tech development centre with support from the ministry of IT and communications, Davra gained nearly 6,000 registered users within its first week of operation.

But these local networks cannot hope to compete with their massive international counterparts. According to the independent US-based online market research company Internet World Stats, Uzbekistan has 450,000 Facebook users, and at least 900,000 others use the Russian social network Odnoklassniki.

Though Uzbek social media provides the perfect advertising platform for local business, they are also seen as a way for the state to try and lure media users to domestic networks, where it is easier to monitor activity.

Photograph: Davra.uz

The most popular Uzbek social network, Muloqot.uz, currently has more than 170,000 users. Registration is compulsory to access this service. Although user data is securely encrypted, its servers belong to state communications provider, Uztelecom.

For this reason many young Uzbeks prefer to use Facebook and Russian social networks for private messaging, even though they’re aware that these platforms are not completely secure either.

Elsewhere the government has shut down sites such as Ozodlik, run by Radio Free Europe/Radio Liberty, the BBC Uzbek service, Voice of America and Fergana.ru, while much of the content on Uzbek news sites closely follows the government line.

In its 2015 study on Uzbekistan, US-based rights watchdog Freedom House reported: “State-owned telecommunications carrier Uztelecom maintains control over internet services […] blocking access to the websites of foreign news organisations, human rights groups, and exile publications.”

The report added that social media and blogging was increasingly offering an alternative space for criticism and dissent, which had spurred the government to launch its own version in a bid to “combat the popularity of foreign platforms”.

Spring scare

While Uzbekistan’s government has long focused on blocking independent media and spreading patriotic messages, the focus on controlling online space is fairly recent.

It was only following the Arab Spring of 2011 that Uzbekistan really began to strengthen its monitoring efforts. That year, when users of online forums began discussing the protests in the Middle East and North Africa, they soon found that access to pages with news from the region had been blocked.

According to Bahodir Namozov, head of the Association of Prisoners of Conscience in Tashkent: “The authorities are afraid that hidden facts about their ruinous policies might come out via the internet.”

Arbuz, one of the country’s most popular discussion platforms, was temporarily shut down in mid-February 2011 after users began discussing the uprisings and criticising Uzbekistan’s own political and economic situation.

Access to the forum was subsequently restored, but sections on domestic and international politics were removed. By December 2011, Arbuz’s owners shut it down for good, fearing problems with the authorities.

The government then rolled out a campaign denouncing the internet as a “destructive force” against which “a coordinated fight” must be waged.

Photograph: Scott Peterson/Getty Images

In a subsequent move that was interpreted by users as a surveillance attempt, Uztelecom blocked Skype and Viber voice calls from late 2014 until October last year, leaving users with only the messaging option. The communication provider claimed that the service was unavailable due to “routine network improvement”.

Tech tricks

But the Uzbek authorities have learnt that simply blocking websites can have only limited success. Local users have picked up technical tricks to out-manoeuvre cyber censorship, from proxy servers to VPNs and Tor browsers.

One 27-year-old in the capital Tashkent, who asked to remain anonymous, said she used proxy servers on a daily basis to read material from the Fergana and Centrasia resources in Russia, Radio Liberty, Deutsche Welle, Eurasianet and Uznews.

“The reality we see from living here doesn’t correspond to what they write on the government web portals,” she explained. “So we go around the blocks and read independent material.”

Another student who said he too used proxy servers, putting up with their occasional slow speed. “I’m interesting in objective news about politics,” he said. “I get round web censorship to find out the truth.”

With mobile internet use also growing, securely encrypted cloud-based messaging apps, such as WhatsApp, are increasingly popular. And it’s not just affluent city dwellers using these technological tricks: the huge student population as well as activists in the region are now increasingly aware of how to slip past the censors.

A version of this article first appeared on the Institute of War and Peace Reporting’s website

Inga Sikorskaya heads the School of Peacemaking and Media Technology in Bishkek, Kyrgyzstan. She previously served as IWPR editor for Uzbekistan and Turkmenistan